Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, people have needed a special place to store their shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.

Piggy banks of the ancients

“If you know how to spend less than you get, you have the philosopher’s stone.”

Benjamin Franklin

Old Ben Franklin was known for his pithy statements about thrift. But the underlying sentiment of this remark will forever be the key to personal financial success—and had been for many centuries before Franklin’s day. Where did people stash their pennies before banking, though? They might have squirreled them away in whatever convenient receptacle or hiding spot they thought secure, or maybe they put them in something more impressive. Purpose-made money jars and cash boxes have been around for a couple of thousand years and, just like today’s coin banks, they varied greatly in style. Some were high-quality objects because coins haven’t always been small change.

This marble money jar comes from Hatra, an ancient Mesopotamian city located in modern Iraq. Hatra was a mini-kingdom rich enough to issue its own coins—and to need places to store them.

Source: money jar, Hatra, Mesopotamia, 200–300 CE | Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq | photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

Cheaply made money pots have often been found in medieval dumps. They are always broken because that was the only way to get at the coins. The knob on top is a common design feature found on jars from all over the world.

Source: money jar, Bruges, Belgium, 1300–1500, | Raakvlak (Archeological Service of Bruges), BR09/NDS/1/13/A/84

The pig on the shelf

In the grand history of money, “piggy bank” is a recent term. It has come to refer to any sort of coin bank or money box, no matter its shape or era. The source of the term, or how coin banks got so associated with pigs, is nearly as contested as the murky origins of the dollar sign.

One popular theory has it that the origin of “piggy bank” dates back to 15th century England. Many storage pots of that time were made of a cheap, rough, red clay supposedly called pygg. This may have led to the term “pygg bank” when the pots were designed to hold coins. These containers had a coin slot on top and no means of removing the money until the pot was broken. This removed much of the temptation of spending your ready cash, a feature of coin jars that seemed to evolve everywhere independently. In late 18th and early 19th century Europe, these pots began to be made to look like pigs, and porcine coin banks became iconic. They are still icons of saving to this day.

However—and this is a big however—etymologist Michael Quinion claims he has been unable to verify a record of the term pygg in reference to rough clay. Anglo Saxon has a few variations on words for clay that, through some pronunciations, may have resembled “pig.” There is also some evidence in the old Scots language for the term pygg referring to some earthenware products. But this is all very speculative and possibly a case of putting the historic cart before the horse—language wise.

Pigs of the South Pacific

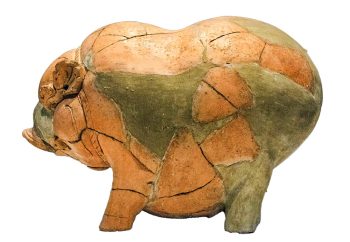

As it turns out, boar-shaped coin banks have been holding people’s personal fortunes in Indonesia since the 1100s! This is several centuries before piggy banks—and anything pygg related—appeared in the West. These banks were called celengans, derived from the ancient Javanese word celeng, meaning pig. How they could have influenced Western coin banks has not been made clear. It could just be a coincidence between cultures. Although the Dutch did colonize Indonesia for several centuries…

Because the fate of a traditional piggy bank was to get smashed to bits, few early examples survive. Most of the ones that do are glued back together. This medieval Javanese piggy bank could have held such local currencies as kepeng and gobog or Chinese coins.

Source: coin bank, Mojokerto, East Java, 1200s–1400s | Museum Nasional Indonesia

But why a pig, anyway?

In some cultures, pigs get a bad rap. But for much of East Asia and parts of Europe, pigs are symbols of luck and prosperity—even of fertility. A chubby piggy also has a shape that lends itself admirably to holding coins. Squirrels might be better metaphors for saving and storing, but how many loonies could you stuff into a squirrelly bank?

As its agrarian society became wealthier, the Majapahit Empire of what is now Indonesia began importing large amounts of Chinese copper coinage for use by less wealthy folks in their daily economy. This sort of money may likely have been the contents of an average Javanese piggy bank.

Source: 1 cash, Ming Dynasty, China, 1368–1398 | NCC 1974.151.3416

But it was (and is) the pig’s vital role in modest households that may provide a theory as to why it became such a popular shape for a coin bank. A pig—a real one—is an excellent store of value. Few animals convert food into flesh as efficiently as a pig, so investing your money in a piglet and then feeding it with table scraps and garden waste will result in a very solid porker by the end of the season. Its sale at market or slaughter for home use is a far greater return on investment than tossing the occasional coin in a jar. Raising a pig as a storage place for value is still practiced in many countries. There is also an interesting parallel between slaughtering a pig and smashing a piggy bank.

The professional piggy bank

Before banks were common (and trusted), coin banks were often the only means people had of protecting their savings. Well into the 20th century, filling a piggy bank was more often an adult’s activity than a child’s.

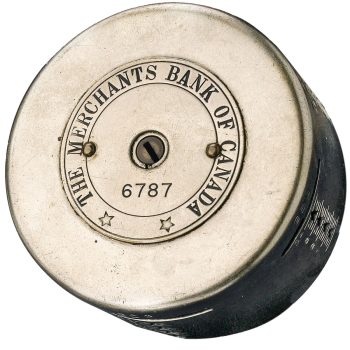

Using a coin bank didn’t necessarily mean you didn’t have a bank account, however. Your bank might have offered you something called a home savings bank, a sturdy little strongbox with a lock. Except the key wasn’t supplied with the box. You would visit your bank branch, where the box would be opened and the contents put into your account. In some cases, a bank representative might visit your home, unlock money box and collect the cash to later deposit it in your account. This was especially convenient for rural customers.

By the late 19th century, most coin banks, especially the piggy variety, had become fanciful things, cute things. And as the 20th century got underway, and commercial banks became commonplace, piggy banks as serious savings tools mostly became things of the past. But there is one stratum of society that still uses piggy banks: kids. To them, a coin carries substantial value—especially now that coins replaced our Canadian one and two-dollar bills. And this is where a fun, fanciful, kitschy coin bank comes in. There is still a ready market for them, and they can be vital tools for early financial literacy.

And now: a few coin banks from the National Currency Collection

Of course, we at the Bank of Canada Museum have to be more serious about what are popularly called piggy banks. They are officially known as “still banks” and, if they have some sort of mechanism to drag money into them, “mechanical coin banks.” Really, we just call them all “coin banks.” Of the dozens of banks—of either species—in our collection, only a handful are pigs. Others resemble clowns, coins, buildings, vaults, books, cans, bank notes, ducks, mice, bears, cars, police officers, barrels, US presidents, mailboxes, automated banking machines, fast food icons and any number of versions of the lockable money box. Some even grab your pennies and drag them inside.

No matter how serious their basic purpose, modern piggy banks have another role: expressing a sense of whimsy. And all of our shelves would be the duller for their absence.

The Museum Blog

New Acquisitions

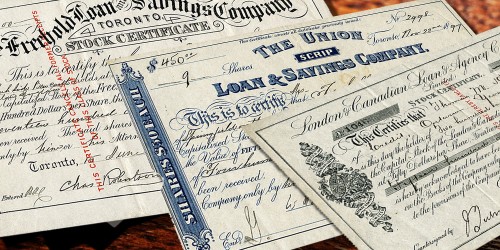

The Canadian financial system of today is diverse… A little known but once prolific system member was loan and building societies. These firms made loans for the construction or purchase of property against mortgages as collateral.

New Acquisitions

Everyone loves getting presents, and we’re no exception. We recently received a very exciting donation of 50 silver coins. The collection was purchased in Lima, Peru, at an estate sale in the 1950s.

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning IX

Our little team from the Museum stood in the education space of the Sherbrooke Nature and Science Museum on a chill November morning while the exhibition technicians assembled our finished exhibition. Yes, finished.

An Exhibition Installation

You could work in the exhibition-fabrication business all your life and still run into things you wouldn’t expect: a never-ending series of “uh-ohs.” It’s one of the things that makes the job so interesting and demands a high level of creative problem-solving skills…

New Acquisitions

What do you think of when you think of money? Is it coins? Is it bank notes? Three-hundred years ago people weren’t sure bank notes were really money; it took a long time for them to get used to the idea.

Royal Canadian Numismatic Association Convention

The show… is an ideal opportunity for the Bank of Canada Museum to share a part of the National Currency Collection with Canadians. This year, we decided to tell the story of Canada’s phantom banks and the financial crisis of 1837.

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning VIII

On this trip, we were all excited to see the 8-foot-tall wooden panels with the full copy printed directly onto them. Using a new process, staff of the exhibition fabrication department at the Sherbrooke Nature and Science Museum have produced some very impressive results.

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning VII

An exhibition fabrication company was finally selected by the Museum to produce the upcoming “Voices from the Engraver” travelling exhibition. It’s all very exciting.

New Acquisitions

The recent additions to the National Currency Collection described below are from very different parts of the world and are between 1500 and 2500 years old.

The Big Nickel

The commemorative 1951 5 cent piece was issued to mark the 200th anniversary of the naming of nickel and its isolation as an element. Recently, I had the great pleasure to participate in the Big Nickel anniversary festivities and give a talk about the design competition for the 1951 5 cent coin.