Tender loving care for a significant artifact

It’s not all currency. The Museum holds 1000’s of items related to the business of making money—literally. The addition of a 19th-century printing press to the vaults presented some unusual challenges to the collections team.

A venerable printing firm donates its history

In 2012, the Ottawa-based security printing firm BA International closed. Formerly the British American Bank Note Company, BA had been printing bank notes, passports, bonds and other secure documents since before Confederation. With this closure came an opportunity for the Museum’s National Currency Collection (NCC) to acquire objects that showcase the production processes used by BA and other security printers. Luckily, one of the pieces offered to us was a large production tool known as a spider press.

A 500-year-old tradition

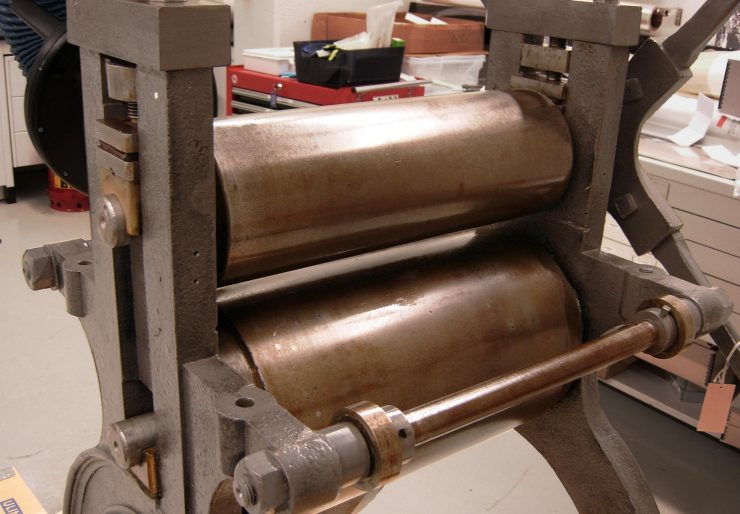

Used extensively in the 19th century, this type of hand-operated press printed secure financial documents using the intaglio method. Intaglio literally means carving, and initially, an image would indeed be carved (engraved) into a soft steel plate. This plate would be coated in ink and wiped with a cloth to remove the ink from the non-engraved surfaces. It was then placed on the press underneath a clean sheet of paper. The press operator would turn the machine’s hand wheel, rolling the plate-and-paper combo between two large, heavy cylinders. The pressure of the cylinders would push the paper into the ink-filled areas, leaving a raised print on the paper. The multiple spokes of the hand wheel, reminiscent of the legs of a spider, gave rise to the name “spider press.”

The press is stored on a pallet and moved with a hydraulic jack. It takes four strong people to shift it even a few centimetres.

The Devil is in the humidity

When our BA spider press arrived in 2013, we discovered it had been exposed to a greater amount of moisture than expected. The result? A coating of bright orange corrosion had blossomed over all the exposed steel surfaces. As well, years of use had left crusts of dust, dirt and grime embedded in the crevices of the machinery.

As it was not intended to go on display immediately, we decided to treat the spider press before it went into storage at the Museum. The goal was to reverse as much of the damage as possible and hopefully prevent further active corrosion from appearing.

Gentle treatment for a heavy machine

After several spot tests, we decided that the corrosion should be removed with extra fine steel wool followed by gently wiping the surface with soft cloths and alcohol. The embedded dirt and grime was then removed with cotton swabs lightly dampened with mineral spirits. Finally, a thin layer of machine oil was applied to all the metal surfaces to act as a protective coating.

Putting the spider press to bed

Once the press was moved back into storage, it was sealed in a tent of polyethylene sheeting along with packs of moisture-absorbing silica gel. This created a drier micro-climate around the press. The condition of the spider press will be monitored as it remains in storage, making sure this valuable artifact will be around for generations more.

With the treatment fully complete, the rolling bed was re-installed between the upper and lower cylinders and the press photographed for the database.

Stay tuned for a further blog on the conservation of some of a large collection of intaglio printing plates obtained along with this press.

Teaching math using money

By: Jonathan Jerome

Caring for your coins

By: Graham Iddon

Security is in the bank note

By: Graham Iddon

Teaching art with currency

By: Adam Young

New Acquisitions—2022 Edition

Money: it’s a question of trust

By: Graham Iddon