From skip counting to making change, working with money is a great way for students to practise math skills.

Use these activities and resources to help elementary students flex their math muscles.

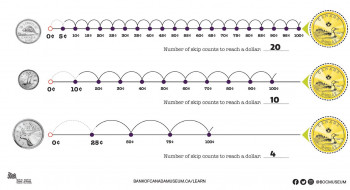

Skip counting

Students can practise skip counting with the help of tools like coins and bank notes. Using either real or play coins (like our own printable play money), ask students to count first by 5, then 10, then 25 until they reach 100. Students can use this skip counting worksheet to keep track as they count. The same approach also works for the higher denominations seen on bank notes.

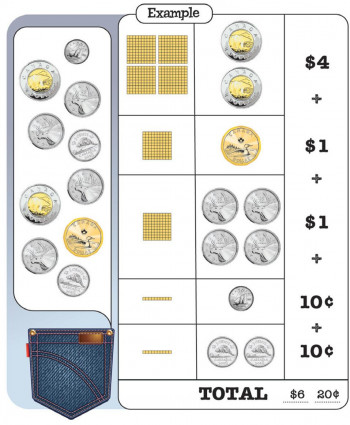

The power of 10

Working with base 10 blocks can help students see the relationship between cents and dollars. First, have students match each denomination of coin with its corresponding base 10 block (5 cents = 5 single blocks, 10 cents = a 10-count rod, $1 = a 100-count flat, etc.). Then give students different amounts of play money and ask them to represent the amounts with base 10 blocks. Lastly, write out amounts on the board and see if students can represent them with both play money and base 10 blocks.

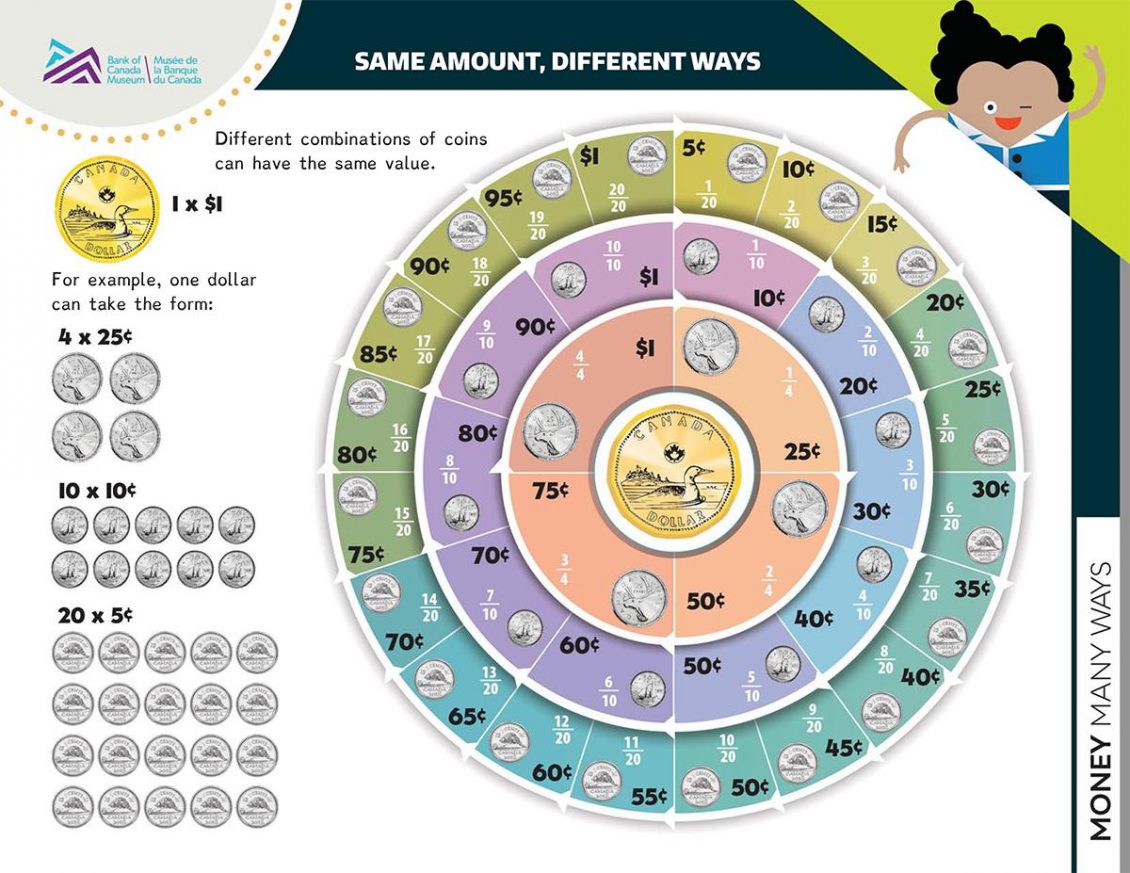

Fractions

Money is a common way we use fractions in daily life. Fractions can be expressed in different ways while still representing the same value, just like how we can use different combinations of coins and bank notes to make up the same amount of money. To help students visualize these equivalent fractions in terms of coins, you can show them the Same Amount, Different Ways chart. Explain to students that this diagram shows how we can express the value of one dollar (or 100 cents) using different coins. The coins show different fractions of a dollar.

Show students one-half, one-quarter or one-fifth of the pie chart by covering part of it. As you cover up different sections, ask students to identify the following for each fraction:

- the fraction in its simplest form (½, ¼, ⅕)

- the equivalent fraction with 100 as the denominator (50/100, 25/100, 20/100)

- the number of cents needed for each fraction of a dollar (50¢, 25¢, 20¢)

- the decimal equivalent for each fraction (optional) (.50, .25, .20)

Show students the relationship between the simple fraction and the equivalent fraction. For example, if you have a dollar and someone takes half of it, that remaining 50-cents is the same as ½ or 50/100, whether it is shown in a simple fraction or out of a dollar. Another example is how we talk about a quarter of a dollar by either saying 25 cents, or, simply, a quarter.

Mental money math

To consolidate the skills students have learned so far, challenge them to explain how they can make a given amount of money with the fewest number of coins and bank notes possible. For example, you can represent 75 cents with seven dimes and one nickel, but that would be more coins than three quarters. Alternatively, ask students how many ways they can represent the same amount of money. This can be done as a mental math exercise. If students need more support, they could use play money, base 10 blocks and skip counting to check their answers.

Making change

For extra practice or as a summative assessment of their money math skills, set up a marketplace role-playing activity in the classroom so students can pay for items and provide change. If you need supplies, our Avatar Market activity includes templates for paper puppets and accessories for students to create their own market. Students start with an allowance of $5 in various denominations of play money to purchase different items of clothing and accessories for their puppets. They will need to make decisions and budget their money since they won’t have enough to buy every item.

Real-life practice

Using money to teach math skills helps to reinforce the idea that math is not just theoretical but has practical roles in our daily lives. Conversely, every time kids use currency, they will be reinforcing these basic math skills—skills they will need for so many aspects of their future lives and education.

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.