Toronto’s million-dollar counterfeiting scandal

In 1880, Edwin Johnson was convicted of putting more than $1 million in counterfeit notes into circulation. Considered the greatest counterfeiter of his day, he was arrested by Ontario’s first full-time police detective, John Wilson Murray, who was the inspiration for the fictional Detective William Murdoch of the popular Murdoch Mysteries TV series.

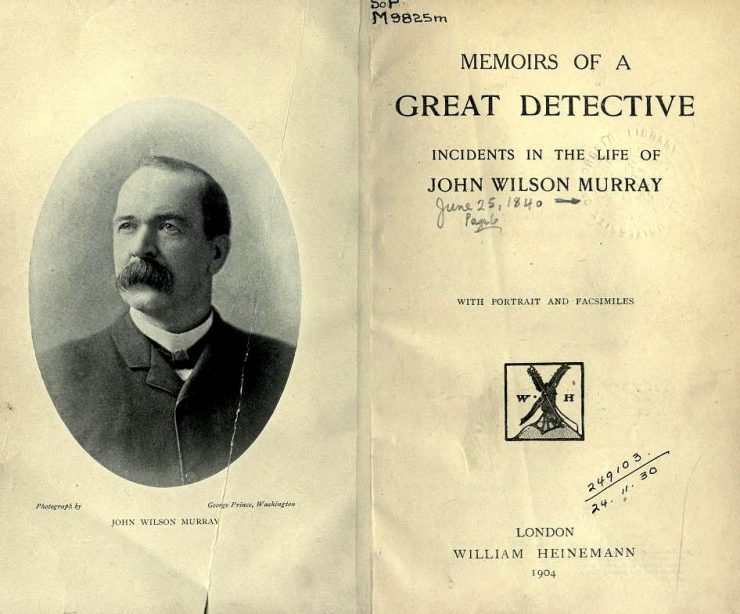

Memoirs of a Great Detective

John Wilson Murray’s 1904 autobiography, Memoirs of a Great Detective, tells the sensational story of how he nabbed the notorious engraver of a great number of phony bank notes circulating in the Ontario economy.

Searching for his man

Murray’s search for a suspect took him to New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Hartford, Buffalo, Detroit and, finally, Toronto. Along the way, Murray spoke to the US Secret Service and the US Treasury Department—and he even contacted counterfeiters and ex-counterfeiters.

On June 14, 1880, after months of searching, Murray found his man: Edwin Johnson. Murray then trailed him, gathering evidence.

Johnson would begin an evening of drinking by spending real notes and then, as he moved from bar to bar, he would start to spend his own fake bank notes. He was finally caught in the act in Markham, Ontario, just north of Toronto.

A photo of John Wilson Murray and the cover page of his memoirs, published in 1904.

Image: Internet Archive: Memoirs of a Great Detective

The Johnson family comes clean

After his arrest, Johnson led Detective Murray to a site just outside Toronto where the counterfeiter had buried 21 of his original printing plates beneath a tree. They had been used to counterfeit eight different government and commercial bank notes.

Johnson’s entire family was involved in the operation: dad made the plates in the United States, his two daughters forged the signatures (they had been practising forgers from a young age), and his five sons were learning to be engravers. At the time of his arrest, Johnson was 75 years old.

The Johnson family printed notes once a year. Afterwards, the plates were encased in beeswax and oil-cloth, and buried. Next, the notes were turned over to a wholesale dealer. The wholesale dealer then placed them with a retail dealer who handed them off to the “shover”: the person who would actually spend the notes. It was unusual for a counterfeiter to pass bogus notes. But during his drinking bouts, Johnson made the mistake of passing his own notes. This was to be his undoing.

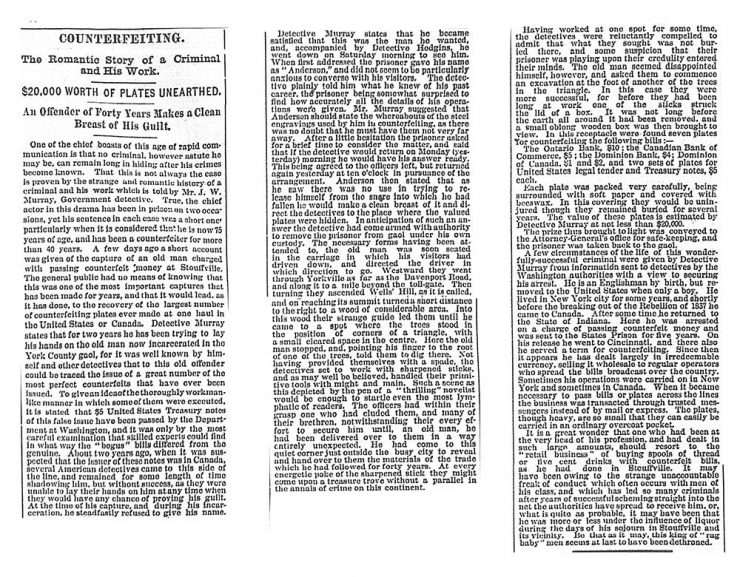

“… for it was well known, by himself and other detectives that to this old offender could be traced the issue of a great number of the most perfect counterfeits that have ever been issued.”

Image: proquest.com, The Globe, June 15, 1880

Separating fact from fiction: a study of Johnson’s counterfeits

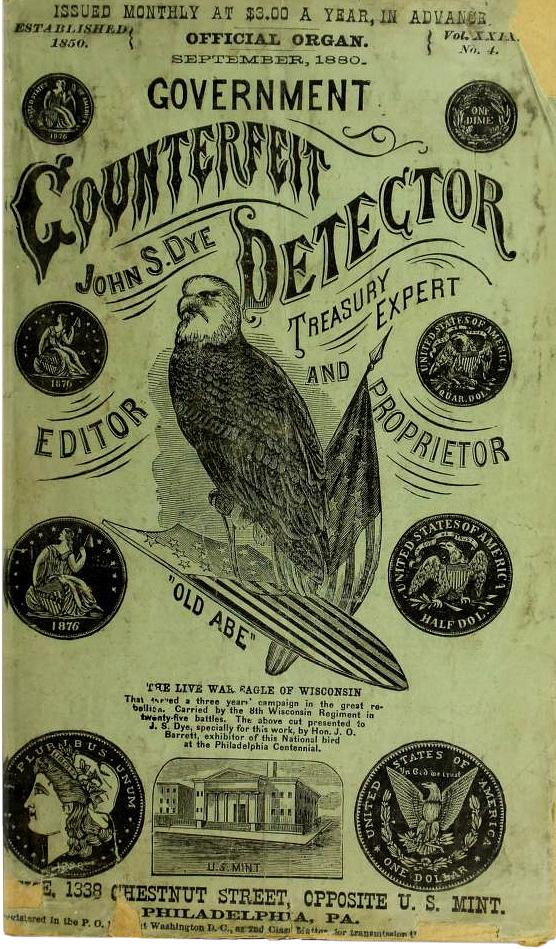

When comparing a counterfeit note with a genuine note, it is easy to see subtle differences. But in Johnson’s era, both government and commercial banks were issuing currency, resulting in dozens of different designs in circulation. It is understandable that even bankers and cash handlers would have overlooked these differences. Certainly, most members of the public were probably not accustomed to handling cash and would not be familiar enough with the security features on a note to be able to know a good one from a counterfeit.

Vital information about the circulation of known counterfeits was published in booklets called “Counterfeit Detectors.” Mostly American in scope, there were several versions that reported on Canadian currency and financial documents. Bankers, cash handlers and merchants subscribed to them monthly to keep track of all the dubious currency in circulation—including Johnson’s counterfeits.

Professional money-makers and money-fakers have acknowledged the superior quality of Johnson’s work. Yet Johnson’s meticulous work would betray him. His counterfeits were far more believable than the usual amateur knock-offs. They were sometimes better than the originals—an aspect that law enforcement officers were able to concentrate on.

[T]he banks took them over their own counters… Officials whose signatures were forged could not tell the forged signature from the genuine.”

John Wilson Murray

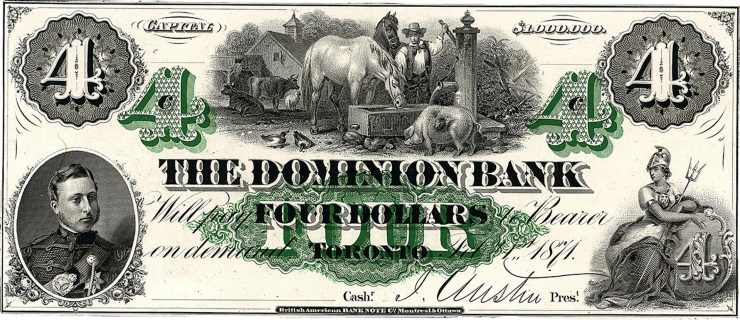

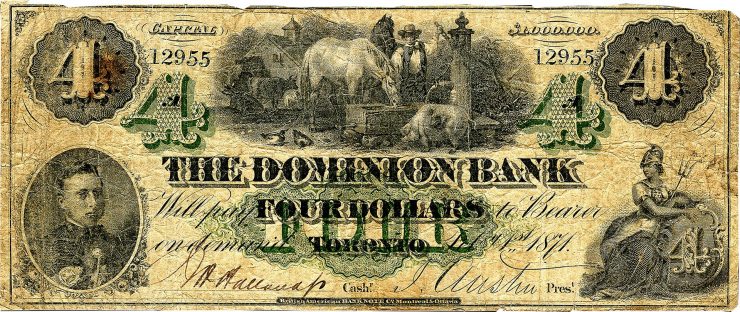

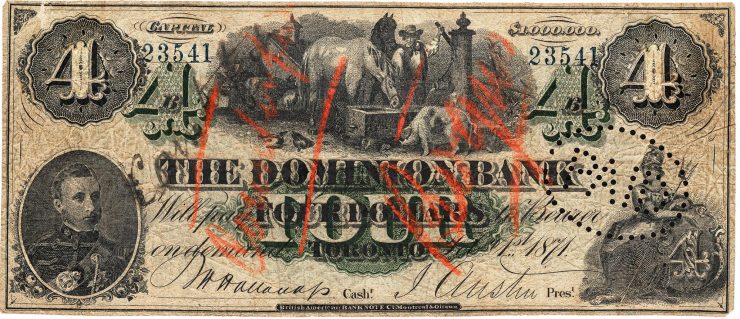

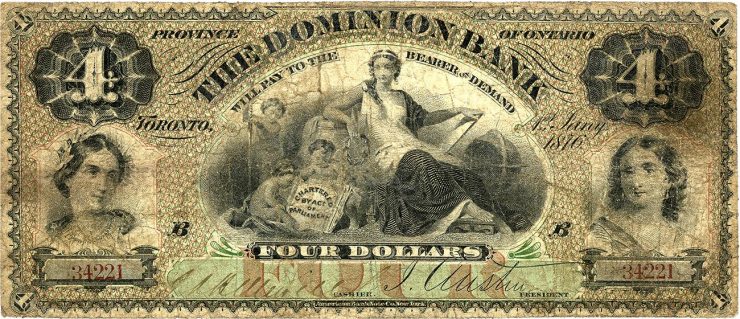

The Dominion Bank

The $4 note issued in 1871 by the Dominion Bank (now TD Bank) is a good example of Johnson’s craftsmanship. This is a very complex note with many design elements. Johnson’s engravings are more refined than those on the genuine note, and the facial features in the portrait of Prince Arthur are more realistic. This stunning counterfeit forced the Dominion Bank to issue a new, more complex and secure $5 note in 1876. The new portraits, a large central vignette and, most important, a red and green background tint, greatly enhanced the security of the note. The addition of colours required more plates and further steps in the printing process, which added to the difficulty of counterfeiting the note.

The Canadian Bank of Commerce

Johnson’s counterfeit of the 1871 Canadian Bank of Commerce $5 bill is perhaps his poorest note. Queen Victoria’s facial features lack finesse but are clear and distinct on the genuine $5 note. Despite the inferior quality of the engraving, the Counterfeit Detectors noted Johnson’s work as “very dangerous.” The spread of these counterfeits prompted the Bank of Commerce to issue a new $5 note in 1879 and to pull the old notes from circulation.

With genuine notes from 1871 being virtually unknown, one from 1867 is used for comparison with Johnson’s counterfeit. This note represents some of Johnson’s poorest work.

5 dollars, Canadian Bank of Commerce, Canada, 1867; counterfeit, 1871

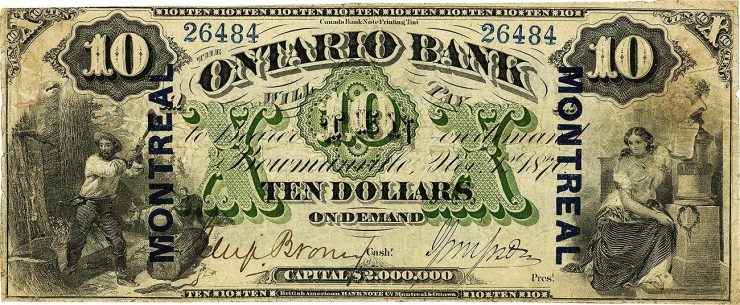

The Ontario Bank

The counterfeit 1870 Ontario Bank $10 note is well executed. However, the Counterfeit Detectors drew attention to the facial features of the lumberjack in the vignette on the left. Upon close examination, they resemble those of a werewolf. A new design for the $10 note was released in 1882 to stifle the spread of the fraudulent notes, although none of these newer notes is known to have survived.

Dominion of Canada notes

In his memoirs, Detective John Wilson Murray alludes to the seizure of Johnson’s printing plates for Dominion of Canada $1 notes. Yet he fails to mention which issue, either 1870 or 1878. Further, The Globe newspaper claims that a Dominion $2 note was also among Johnson’s counterfeits, but Murray makes no mention of this.

So we are left to ask: Which fake Dominion notes are the work of Edwin Johnson? Maybe all of them! We can deduce that there must have been more than one counterfeiter of the 1878 $2 note because there are several different versions in the Museum Collection. Some of them are far too clumsy to be the work of Edwin Johnson. Overall, attempts to replicate the Dominion notes fell short of their mark. The portraits, in particular that of the Earl of Dufferin on the $2 note, are crude and lifeless.

Once again, proofs provide clean, clear and uncluttered details to make it easier to compare good and bad notes. The “bad” note is not likely a Johnson.

2 dollars, proof/counterfeit/counterfeit, Dominion of Canada, Canada, 1878

The trial of Edwin Johnson

Edwin Johnson was put on trial in Toronto in the fall of 1880. He pleaded guilty to seven charges. Because of his age and his gentlemanly co-operation, Johnson was given a suspended sentence. Detective Murray asked that Johnson, along with his daughters, be turned over to the United States to appear before the authorities there. The great counterfeiter died before he could be brought to trial across the border.

Following Johnson’s death, other members of the family relocated to the United States, where they continued their sinister practices. Johnson’s sons were apprehended in different US cities. His son Charlie served time in jail and then moved to Detroit and took up counterfeiting again. He was arrested and sentenced for a second time in 1893. And it wouldn’t be the last.

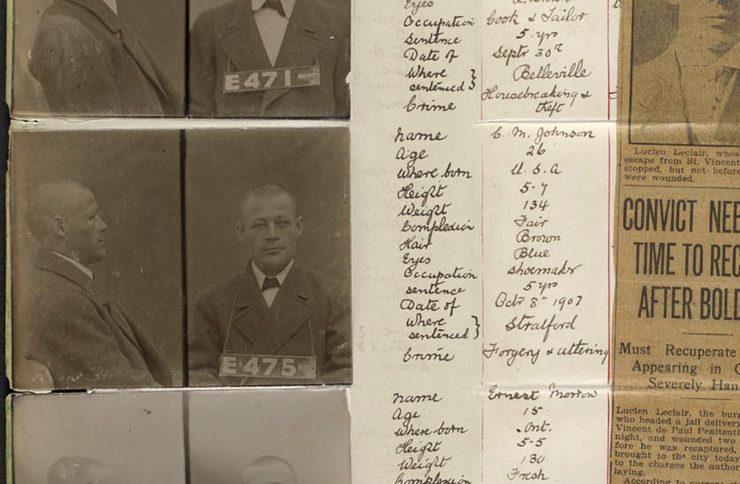

This mugshot of Charlie Johnson comes from a 1907 arrest that was followed by a five-year visit to the Kingston Penitentiary.

Library and Archives Canada, Kingston Penitentiary ledgers, e010995380

Collecting Johnson’s counterfeit notes

Although several attempts were made to counterfeit bank notes in the 19th century, few succeeded in matching the work of the Johnson family. Thanks to John Wilson Murray’s romanticized account of the million-dollar counterfeiting scandal of the late 1870s, collectors and numismatists have been able to identify the distinctive features that characterize a Johnson counterfeit. An appreciation for Johnson’s skill in reproducing genuine bank notes has inspired collectors to preserve his work. There are 370 Canadian counterfeit notes in the Museum’s National Currency Collection. Of these, around 80 percent predate the Bank of Canada, and about 45 of those are believed to be Edwin Johnson counterfeits.

The Museum Blog

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning III

By: Graham Iddon

Notes from the Collection: Recent Acquisitions II

By: Paul S. Berry

Museum Reconstruction - Part 1

By: Graham Iddon

Notgeld, emergency money from interwar Europe

Notes From the Collection: Recent Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry

We’re the Currency Museum, not the Mint

By: Graham Iddon