The imagining and re-imagining of the 1975 $50 bill

Bank note development is a process that can involve more than a dozen contributors at any given stage. And at every stage, major changes can occur. But for the Scenes of Canada $50 bill, these changes seemed especially dramatic.

Sometimes the colour drives the image choice

There could be few more stereotypically Canadian scenes than a lonely, snow-covered cottage on the rocky shores of a frozen northern lake. This was the image originally intended to appear on the back of the 1975 $50 bill. For a series of bank notes with a theme of “landscape with human activity” it seemed an ideal choice. But there was a problem.

The original photograph chosen for the back of the $50 bill is here reproduced as a painting in preparation for engraving. Painting, Canada, 1971, NCC 1993.56.576

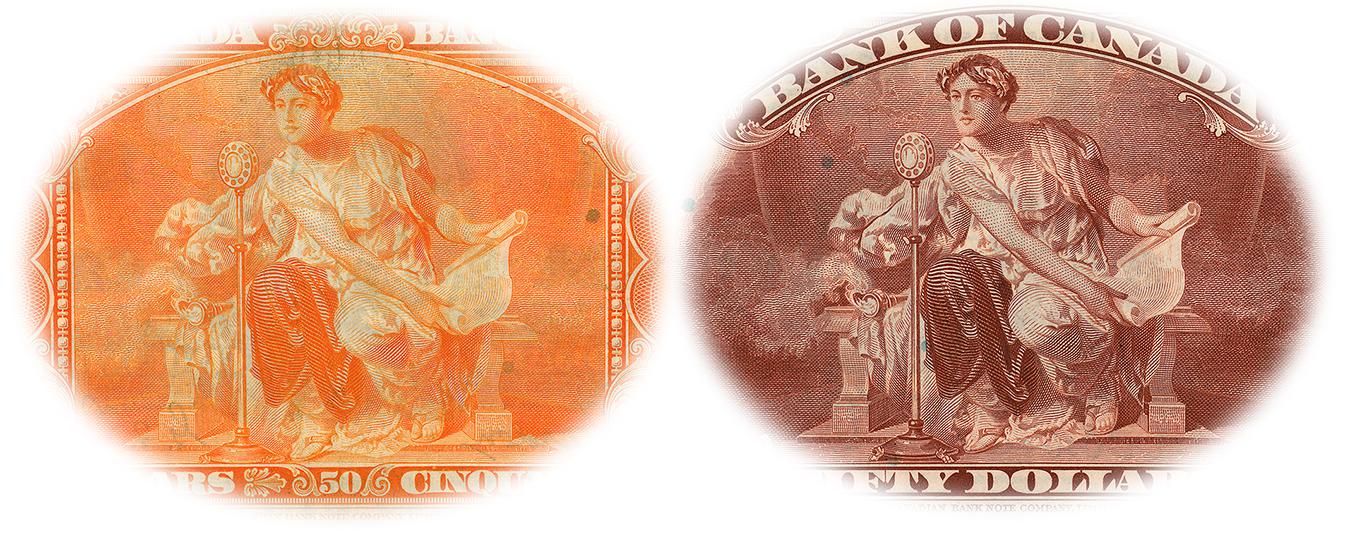

The issue was with the colour. The established thematic colour of Canadian fifties was a bright orange. Unfortunately, it showed few images well—engravings tended to lose contrast and depth. With its many subtle tones, the frozen lake scene was not a good candidate for this colour. So, a new photograph was chosen.

The visual disadvantage of the orange ink is clearly demonstrated by comparing the 1937 (left) with the 1935 version of our $50 bill. 50 dollars, Canada, 1937 NCC 1974.59.2 / 1935, NCC 1984.23.3

Sometimes the image drives the colour choice

Curiously, the new choice was not a landscape at all, but a scene of a ballet company in performance. It was an elegant image and the George Gundersen engraving of it a magnificent example of the engraver’s art. Ironically, at about the time of choosing an image more suitable for the orange theme, the development team decided to abandon the colour.

As it turned out, the ink had more than one strike against it. The flattened tonal range that so limited the choice of images also made spotting a counterfeit more difficult. But the decisive strike was in the ink itself: poisonous heavy metals. The team instead opted for slate grey, a dark greenish colour.

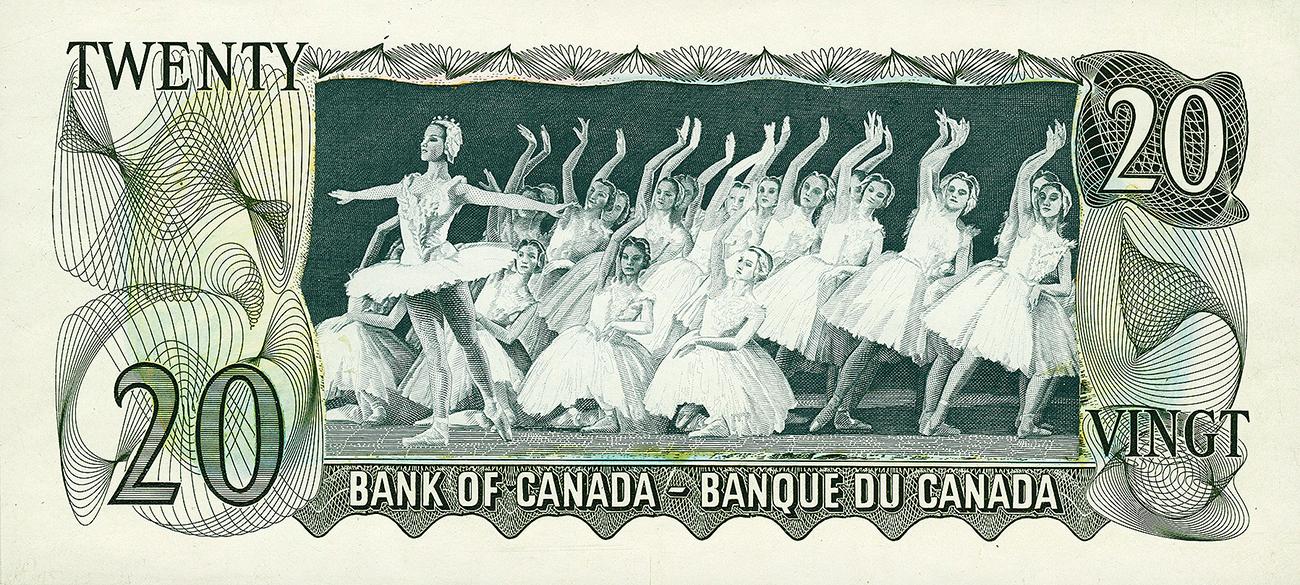

The National Ballet of Canada performs a scene from Swan Lake. The engraving was tested in slate grey ink on a $20 back frame. The $50 back design had not yet been developed. $20, test note, Canada, 1965–70, NCC 1993.56.495

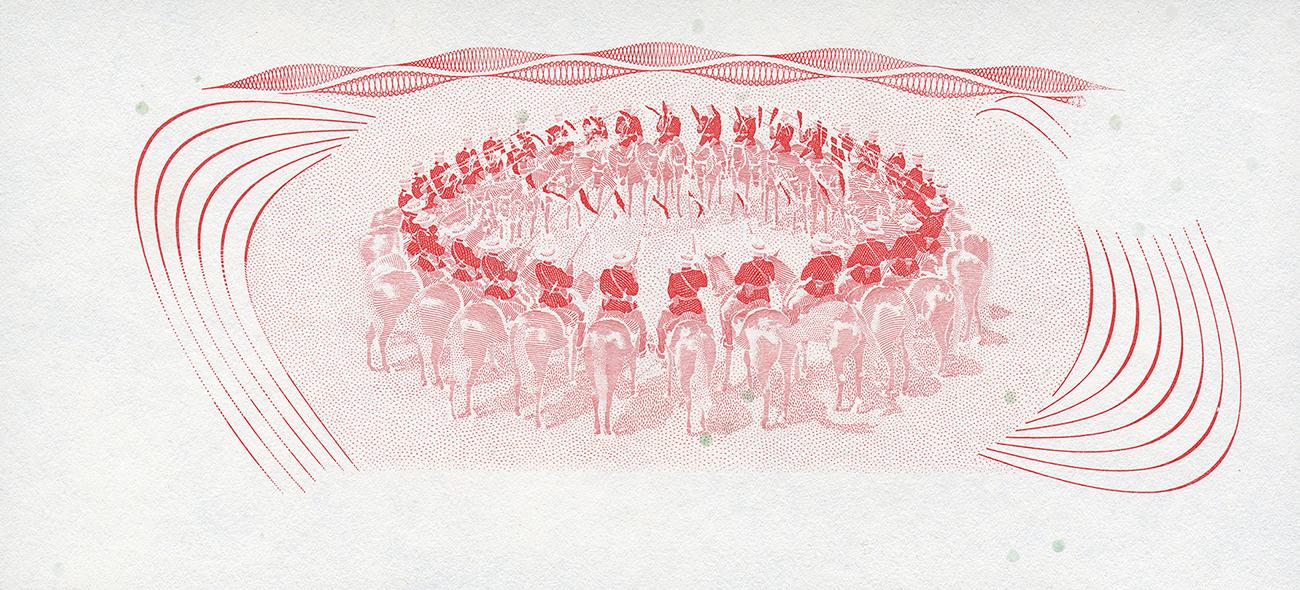

Dark inks in the grey and green ranges show engravings well. The high contrast brings out fine details, presenting a serious challenge to a counterfeiter. But engraver George Gundersen was not happy with this ink choice. Despite a reproduction rich in detail, he felt slate grey made the image appear lifeless. To show the ballet vignette to its best advantage, Gundersen recommended a colour in the purple to red range: between what he called orchid and claret. The grey was rejected, and the red $50 bill was born. But then the image was changed again!

Timing changes everything

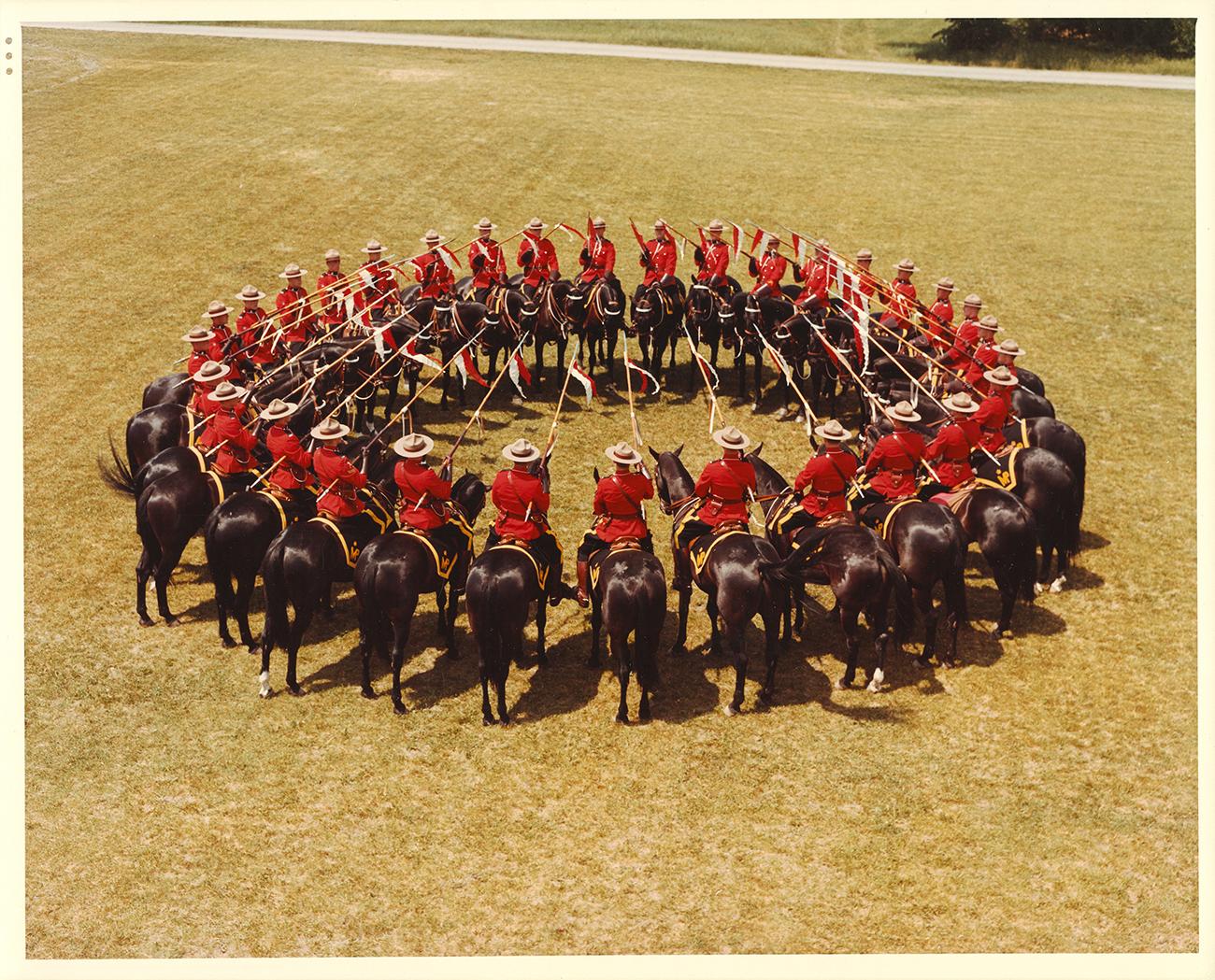

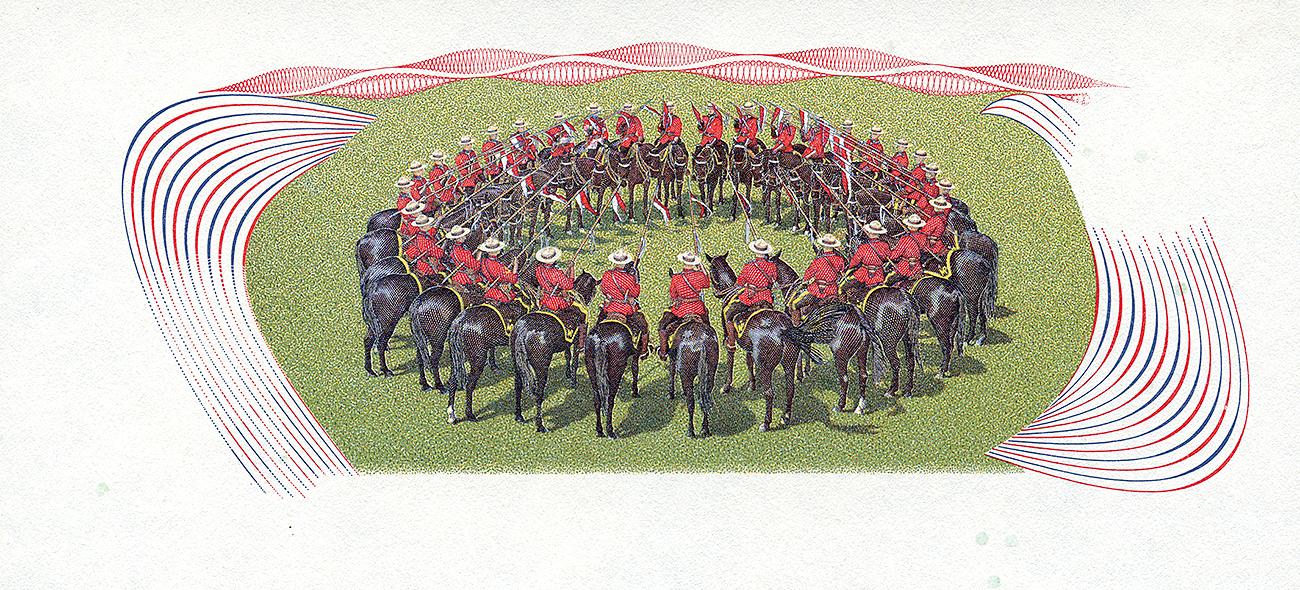

George Hunter, who shot the images for the $5 and $10 bills, was on hand to shoot this image. But he was moved aside to allow the RCMP photographer the camera position. Photograph, Donald K. Guerrette, Canada, 1972 NCC 1990.57.30

The development of this note coincided with the centennial of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). A scientific advisor in the Currency Department proposed that the note could honour the RCMP during its time of celebration. This proposal was accepted. So, yet another image was selected for this note: a photograph of the RCMP Musical Ride in its dome formation. But this note’s long design journey was far from over.

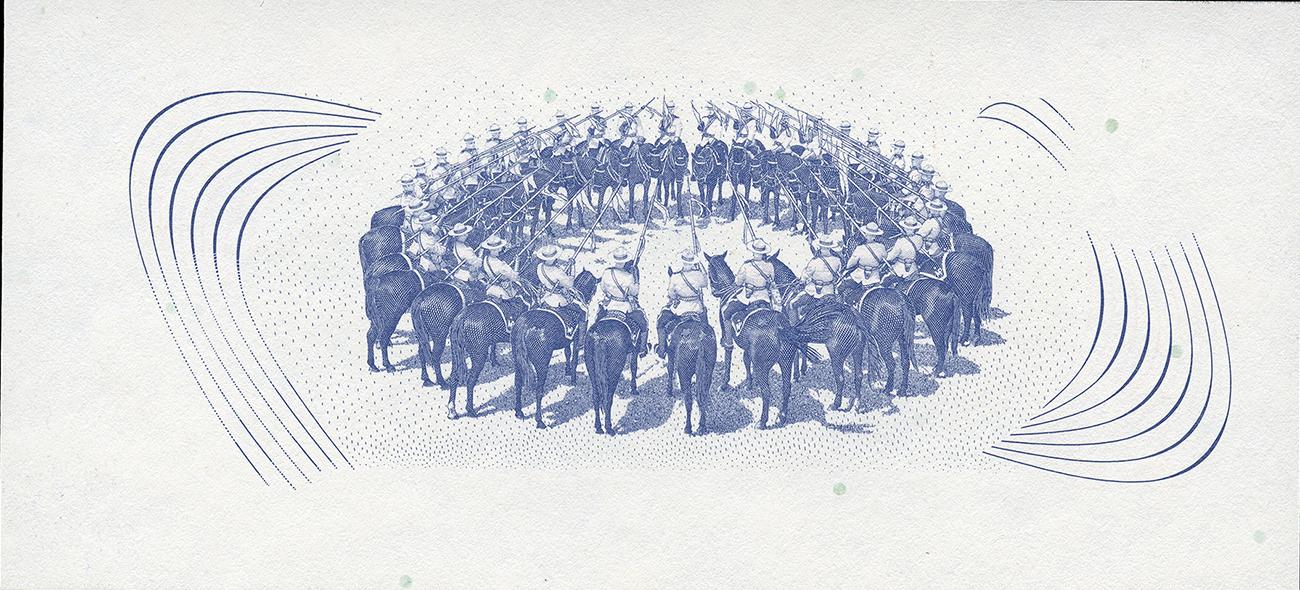

The $50 bill, like all previous Bank of Canada notes, was expected to feature a large engraving on the back. What we call “engraving” is really a printing process called “intaglio,” which begins by carving (engraving) an image onto a steel plate. The image areas are filled with ink and, under the extreme pressure of a printing press, the ink is transferred to paper. The resulting monotone prints are exquisitely detailed with a slightly raised surface. The engraver assigned to execute the RCMP image was a gifted 20-year veteran of the Canadian Bank Note Company, Yves Baril. But this engraver had an ambitious plan.

Mr. Baril’s surprising proposal

Baril’s plan demanded the highest of engraving skills—and it succeeded. But despite the beautiful results, this printing process was considered too laborious and expensive to be practical, so a final major change occurred to this note. Another printing method was proposed.

An engraver embraces lithography

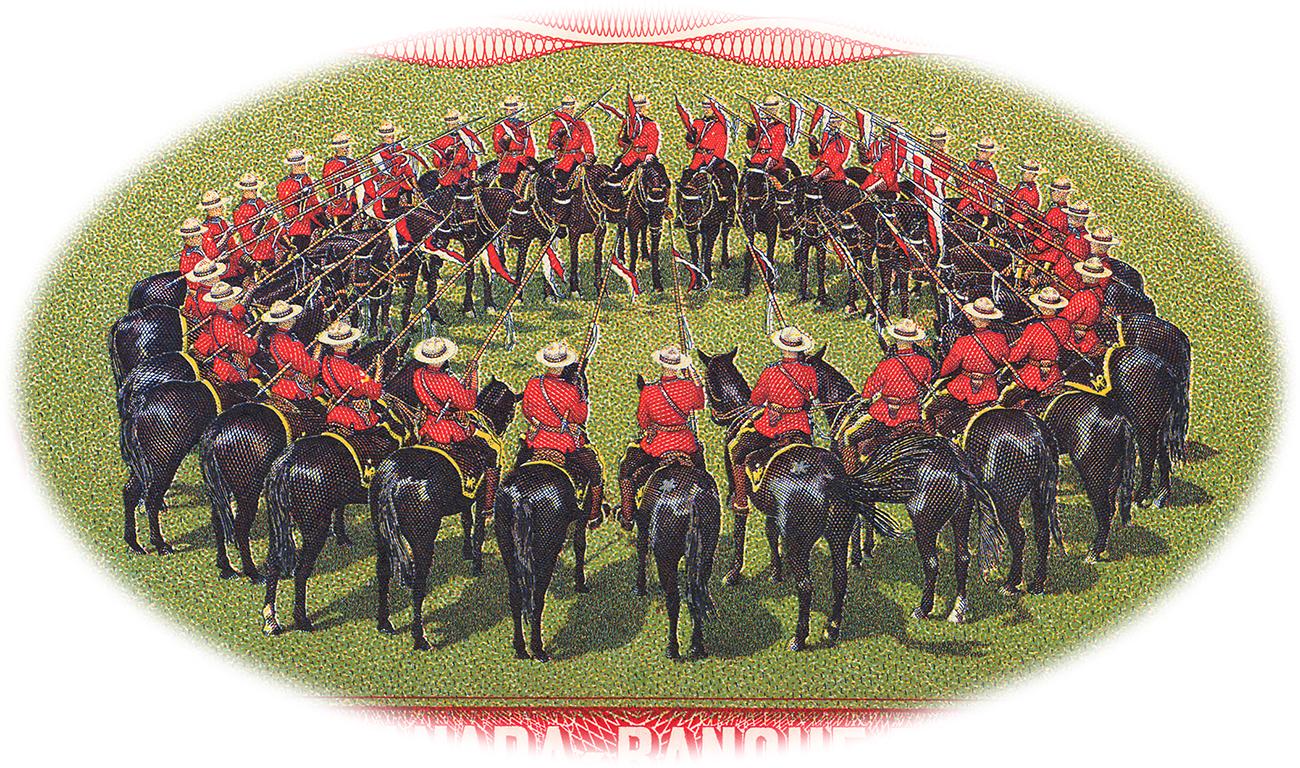

Baril proposed the same layered approach as in his intaglio experiment but using lithographic plates instead. Modern lithography uses a photographic, chemical process to create individual plates. Baril produced five lithographic plates, each carrying one of the fundamental colours seen in the image. They were printed one on top of the other, as in his previous experiment. The resulting vignette was like nothing ever before seen on Canadian money. Richly colourful, it was the signature feature of what became one of Canada’s most popular bank notes.

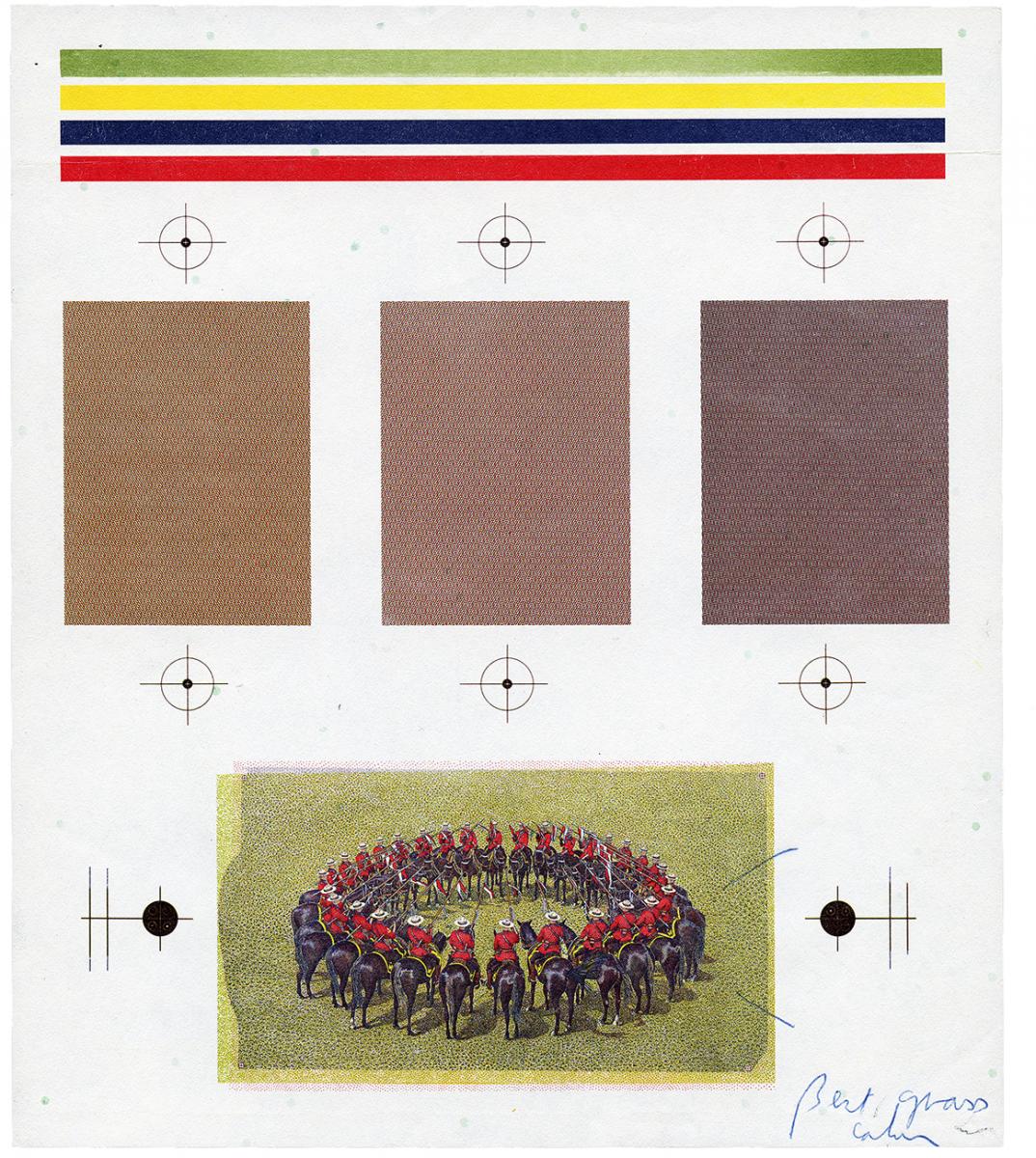

Lithography can replicate photographs, but this was never meant to look like a photograph. The careful layering of basic colours produced a far bolder image. 50 dollars, die proofs, Canada 1974–1986, NCC 2011.67.1562.032–037

A pivotal bank note

The $50 bill issued in 1975 heralded the end of the traditionally engraved vignette. Lithography took over most of our bank note imagery for all the following series. In this way, Yves Baril became the bridge between Canada’s old school of bank note printing and the future. For the 1986 Birds of Canada series, the back vignettes were entirely lithographic. Baril prepared three of the bird images for lithography and hand-engraved the portraits of Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Sir Robert Borden. He retired in 1996, just before planning began for the Canadian Journey series.

The vignette on the $50 bill was a wild departure from the monochrome images of the rest of the series and, indeed, all previous Canadian bank notes. 50 dollars, Canada, 1975 NCC 1975.70.1

Intaglio printing may have taken a back seat to lithography, but it never disappeared. Still used for portraits and other details of bank notes, intaglio’s raised print is a valued tool in the Bank’s defence against counterfeiters. And it is still a beautiful feature.

The Museum Blog

A Good Deal

By: David Bergeron

Esperanto: universal language¬—universal coinage?

By: David Bergeron

Tea brick Currency

By: Raewyn Passmore

Paul Berry is Retiring? Say it Ain’t So!

Money of the First World War

By: Paul S. Berry

Money’s Magnificent Moustaches

By: Graham Iddon