Retired Cash

When money loses its legal tender status

“Legal tender” means a coin or bank note that has been declared by the government to be acceptable for all payments and purchases. So what happens when that status is revoked?

Old money still at work

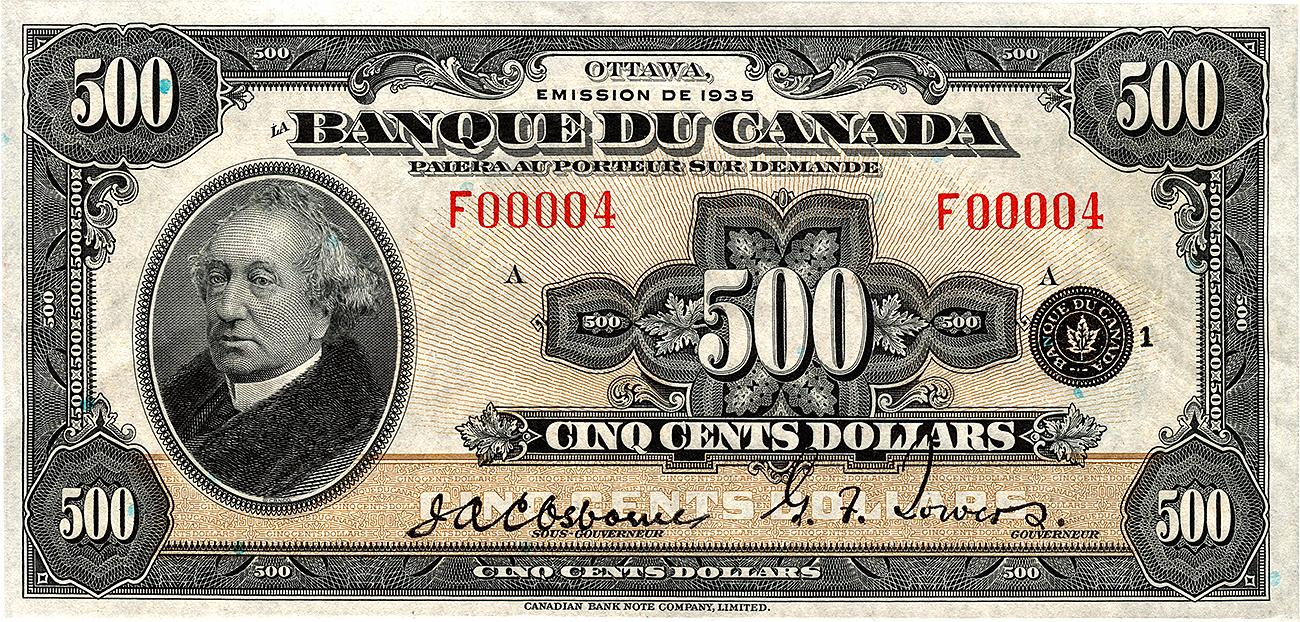

A man walks into a bar and orders a beer. The bartender pours him his drink and says, “That will be $6, please.” The man then slaps down a rather battered Canadian 1935 $25 bill. The bartender could simply place the bill in her cash register and then hand the man his change. This is because bank notes issued by the Bank of Canada typically remain functional money until they disintegrate. No matter their age, those notes are still “legal tender.” But unless our bartender is well informed about Canadian currency policy and numismatic history, she is very likely to refuse that payment. (Or introduce him to the bouncer, depending upon what sort of bar it is.) However, in 2021, she’ll be entirely justified in declining that bank note.

This unique bank note design was issued to celebrate the 25 years of King George V’s reign. It was Canada’s only $25 bill and starting Jan 1, 2021, will no longer be legal tender. 25 dollars, Canada, 1935, NCC 1977.12.1

A little history on legal tender

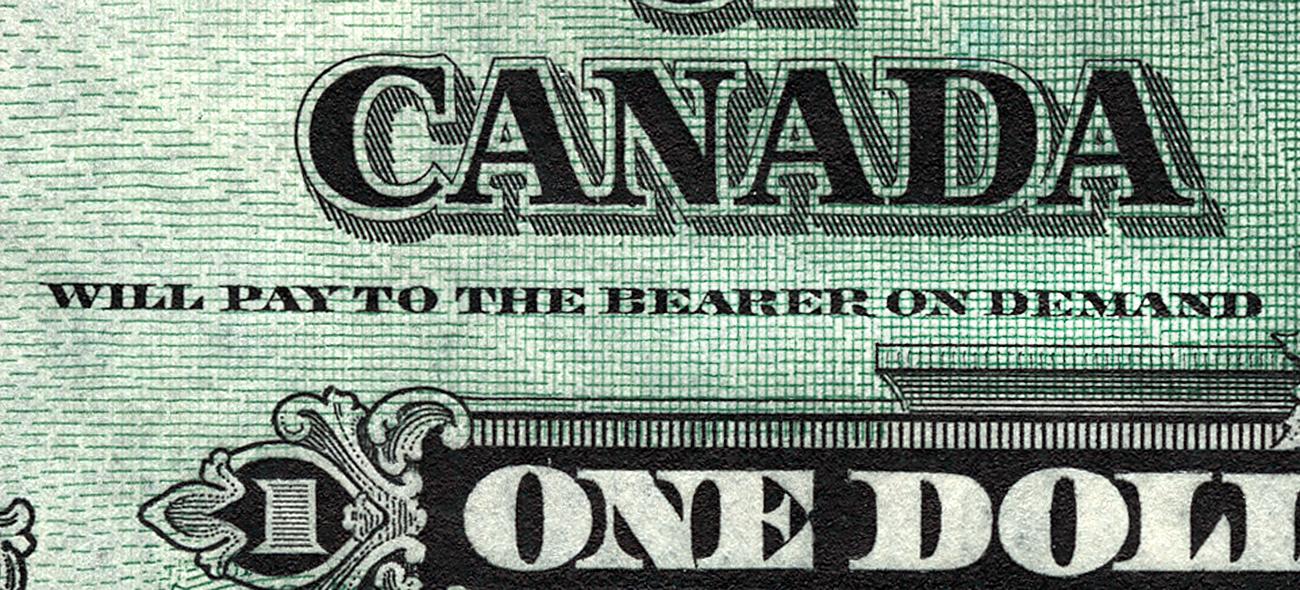

“THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER” has appeared on the face of every bank note issued by the Bank of Canada since the Scenes of Canada series was introduced in 1969. Prior to that, the phrase on every Canadian government bank note read, “WILL PAY TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND.” These are legal terms that reflect two very fundamental differences in how paper currency works.

Up until the Great Depression, Canada was on the “gold standard.” What this meant was every Canadian dollar represented, theoretically, a dollar’s worth of gold held in the government’s vaults. You could go to your bank with a $10 bill and “demand” that the teller exchanges it for $10 in gold coins. This notion of storing the gold but trading the ownership was a centuries-old form of financial convenience.

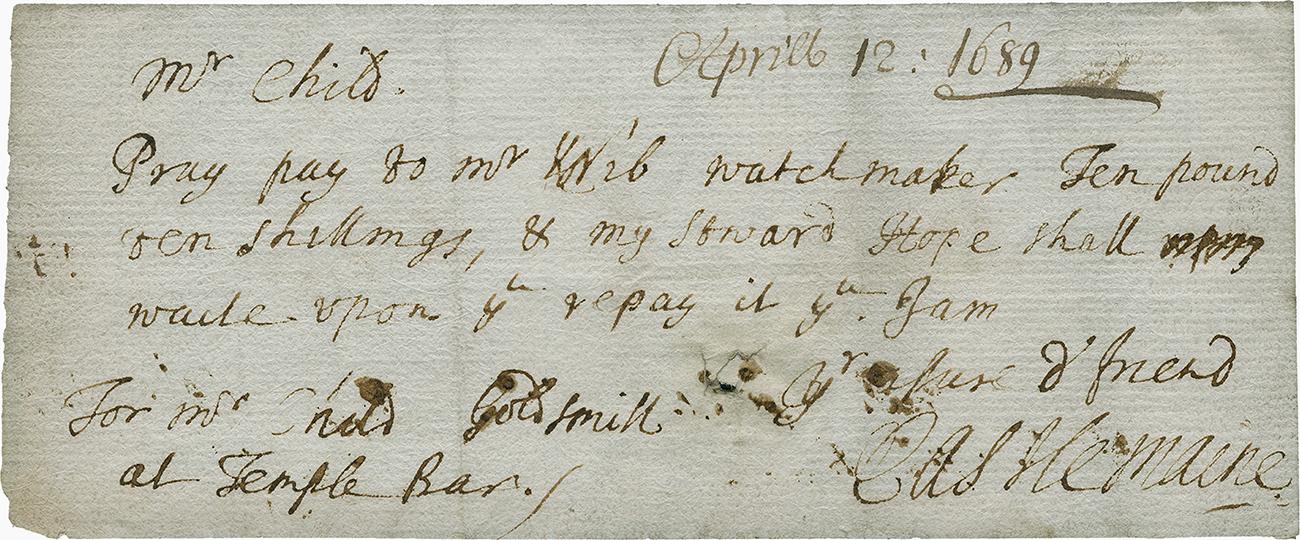

By the time this note was issued, exchanging paper currency for gold was no longer practiced. 1 dollar, Canada, 1937, NCC 1973.1.0

One of the earliest varieties of European paper currency was deposit slips from 17th century English goldsmiths. As well as making you a wedding ring, goldsmiths would store your gold in their vaults. When you wanted to trade this gold for something, it was simply easier to hand over a goldsmith’s deposit receipt rather than transfer all that heavy gold. Clever goldsmiths then began issuing notes representing fractions of their clients’ gold. These notes circulated as money while the gold stayed put in a vault. It was a practical and convenient system.

This deposit receipt from a goldsmith may have passed through many hands before the gold itself was withdrawn from the goldsmith’s vault. 10 pounds and 10 shillings, England, 1689, NCC 1963.48.40

“Legal tender” first began to appear on bank notes when nations went off the gold standard in times of extreme economic need, such as during war. Up until the late 19th century, money was traditionally understood to be gold or silver coins. A bank note was essentially a receipt for coins held in storage, so it was difficult to convince people that legal tender was functional money. But today, such currency is the norm and called “fiat” currency, meaning it is not backed by a commodity such as gold or silver. Rather, it is guaranteed by the government that issued it. Curiously, “legal tender” didn’t appear on Canadian bank notes until the late 1960’s, decades after we went off the gold standard.

This “greenback” is from during the American Civil War. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 allowed the US government to print money not backed by gold to help finance the war. 1 dollar, United States, 1862, NCC 1966.28.9494

Why some notes will no longer be legal tender

The federal government is removing legal tender status from a selection of bank notes because the Bank wants to make sure that the currency is as modern as possible. If an older note is still in circulation and acceptable as payment, it’s a target for counterfeiters—a much easier target than a new polymer note with its state-of-the-art security features. As well, retailers may not even recognize our older money and certainly machines won’t recognize it. The Bank just wants to make sure our circulating currency is as secure and functional as possible.

And we’re not unusual for removing legal tender status from old money. Currently, more than 20 central banks have the right to do so. The Bank of England regularly removes legal tender status from an old design when it issues a new note, and countries in the European Union did the same to their national currencies when they adopted the euro.

Notes you can take to the bank

The notes losing legal tender status are all denominations long out of circulation: $1, $2, $25, $500 and $1000. Most of these notes will be entirely unknown to the majority of us and it’s unlikely you will ever come across any in your change from the doughnut shop. But, if you do come across some of these denominations, don’t despair; they are still worth their face value. You just need to take it to your financial institution, where you can either exchange it for new currency or have the value of the note deposited into your bank account. You can also send it to the Bank of Canada to be redeemed.

This is a sampler of the denominations and series that will lose legal tender status. For a complete grid of these bills, see the Bank’s webpage on the subject. 500 dollars, Canada, 1935, 1 dollar Canada 1937, 2 dollars Canada, 1954, 2 dollars Canada, 1974, 1000 dollars Canada, 1986

Don’t judge a bill by its denomination

According to statistics, there are millions of old bank notes that the Bank has been unable to remove from circulation and therefore still constitute money—money it is still responsible for. Though many are in collections, it is likely that the vast majority have been lost or destroyed, especially the low denomination notes. But they do occasionally pop up in circulation. If not too damaged or badly worn, some of these notes will be worth more than their face value on the collectors’ market. And our thirsty customer’s commemorative $25 bill? Well, let’s just say he might be able buy a round for the whole bar with the value of that particular note.

Have you run across any of these notes? Before you cash them in for their face value, you might want to check in with a coin dealer or have a look at a price guide. You never know what you might have. Either way, you can’t lose!

This is the holy grail of Canadian bank notes. A handful are in collections, but so few are unaccounted for that their value can only be guessed at. 500 dollars, Canada, 1935, NCC 1984.23,73