In 1896, three enterprising men struck gold in the Klondike region of the Yukon. Their story is just one that illustrates the allure of gold through the ages—many more tales lie behind the outstanding gold coins in the National Currency Collection.

Gold fever in Canada

In mid-August 1896, American George Carmack and Tagish First Nation members Keish (Skookum Jim Mason) and Kaa Goox (Dawson Charlie) discovered gold in Rabbit Creek, a small tributary of the Klondike River in the Yukon. The creek was later renamed Bonanza Creek, and over the next several years prospectors stampeded to the region hoping to get rich. Though it was relatively short lived, the Klondike Gold Rush caused a media sensation that people throughout North America experienced, whether they were prospectors or not. It left its mark on both the Canadian and American psyche and has been immortalized in literature, film and music.

The allure of gold

But gold fever was nothing new. The precious metal has been highly prized by different cultures throughout human history. It figures prominently in myths and sacred texts, in art and popular culture. Its mythic qualities are largely connected to its physical properties: gold is resistant to corrosion and highly malleable, and its constant lustre is visually appealing. It’s also rare—a quality that made it suitable to be turned into money.

Prospectors faced an arduous journey to reach the Klondike goldfields. From the Alaskan ports of Skagway and Dyea, they trekked hundreds of kilometres to the Yukon River carrying one year’s provisions on their backs.

Source: Photograph, Packing up Chilkoot Pass, c. 1898–99, Library and Archives Canada / C-004490.

Ancient coins

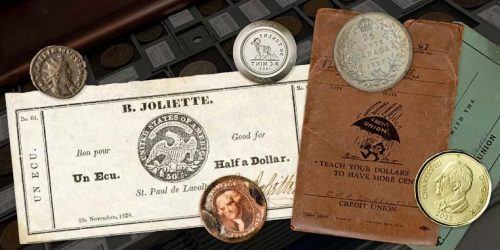

Most historians agree that the first coins were struck in the Kingdom of Lydia, in present-day Turkey, around the 7th century BC. They were made of electrum: a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. Later, during the reign of King Croesus from 560 BC to around 546 BC, the Lydians developed methods to separate the metals to mint both pure gold and pure silver coins. One gold piece was worth 10 silver ones.

In addition to simplifying trade, coins became an important way for rulers in the ancient world to show their power and influence. These rulers stamped their portrait, or effigy, on coins that then circulated throughout their kingdoms. The coins could also be used to celebrate the life of an important person. In 140 AD in ancient Rome, Empress Faustina the Elder died. She had been well liked and respected during her life. To honour her, her husband Emperor Antoninus Pius asked the Roman Senate to deify her and had her portrait stamped on coins.

Medieval coins

Minting gold coins created a common medium of exchange that was widely accepted throughout different parts of the Medieval world. On the Mediterranean coast, trade relations between Italian city states and Islamic kingdoms in North Africa, such as the Hafsid Kingdom in present-day Tunisia, ensured a steady exchange of goods and gold across the sea. The reserves of gold amassed in Florence as payment for its exports allowed the city state to become a leader in banking and to mint its own gold coin: the florin. First issued in 1252, florins continued to be struck until 1533 by which time the Venetian gold ducat (which had been modelled on the florin) had replaced it as the trade currency of choice in Europe. The ducat remained in circulation for another 200 years.

Tunis (Tunisia) was the capital of the Hafsid Kingdom. Tunis was strategically located for trade, with access to the Mediterranean Sea and the inland caravan routes that crossed the Sahara Desert.

Source: Coin, Mohammed I al-Mustansir, 1 dinar, Hafsid Kingdom, c. 650-675 AH (c. 1263-1277 AD), NCC 2000.40.682

Gold in the Age of Exploration

During the 15th to 17th centuries AD, the widespread use of gold as a currency made it an important resource for nations to acquire. But they did not always acquire it by trade; sometimes they took it by force.

When Christopher Columbus sailed west from Spain in 1492, he had planned to go to Japan in search of the gold that Marco Polo described in his book, Travels. Instead, Columbus found himself in the Caribbean where a wealth of mineral resources lay beneath the ground. The allure of gold also brought Hernan Cortés and other conquistadors to Latin America throughout the 16th century.

Their greed ultimately caused the destruction of the Indigenous population in what historians have described as the first large-scale genocide of the modern era. Much of the gold that was plundered had initially been worked into sophisticated objects of cultural significance, but the conquistadors were only interested in the raw material. They melted the gold into ingots, which could be more easily sent back to Spain to be minted into coins or used as payment to foreign governments.

Soon, Spanish-owned gold and silver mines were established, where Black and Indigenous slave labourers pulled the precious metals from the ground. At the same time, local mints opened to process the material into coins. The resulting influx of gold and silver to Spain expanded the money supply throughout Europe, causing widespread inflation.

Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the Caribbean was sponsored by King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I, joint sovereigns of Aragon and Castille (Spain). Their crowned effigies graced the front of Spanish coins until 1537, several years after their deaths.

Source: Coin, Ferdinand II and Isabella I, excelente, Spain, 1497–1537, NCC 2008.60.1

In 1521, the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan was conquered by Spain and renamed Mexico (Mexico City). By 1536, a mint had opened to supply currency for the growing city. Gold cobs, or escudos, were minted there until the 18th century.

Source: Coin, Philip V (Spain), 8 escudos, Mexico mint, 1714, NCC 2015.24.1

West African gold

On the gold-rich coast of modern-day Ghana, the Portuguese established a trade presence around the 1460s. By the mid-1600s, competition from the Dutch, the French and the British had intensified with the British gaining control of trade in the area. England founded the Royal African Company in 1672 with the primary purpose of importing gold from West Africa. The company quite literally left its mark on British economic and monetary history: its logo can be found on some of the gold guineas minted in England at the time. The company was also involved in the slave trade. By the early 1720s it had trafficked around 150,000 men, women and children across the Atlantic aboard its ships—a horrific legacy on the West African coast.

This guinea was made with gold imported from West Africa by the Royal African Company whose logo, the elephant and castle, is visible below the effigy of James II. He was the company’s first governor before becoming king.

Source: Coin, James II, 1 guinea, England, 1687, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, estate of Josiah K. Lilly Jr., NU.68.159.3649

Evolving uses and new sources

Gold has had a profound impact on civilizations throughout the ages, both economically and as a part of cultural practices and mythologies. But its use is also wrapped up in colonial legacies and stories of human and environmental exploitation. And while our money might not be made of the precious metal anymore, gold is still an important resource, used in everything from crowns for teeth to computer chips.

These days, though, gold doesn’t always come from mines or rivers; it can also be sourced from old, recycled electronics. The wires and computer chips inside these devices contain many precious metals that would otherwise go to waste. Innovations in the ways we source and use this important metal are likely to continue as the impact of resource extraction on climate change becomes more pronounced in the coming decades.

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.