Economic bubbles from flowers to bytes

An economic bubble is aptly named. It is a delicate thing that rises and floats on a warm updraft of enthusiastic optimism. But, just like a soap bubble, an economic bubble has a tendency to burst. And somebody, or a lot of somebodies, will get soap in their eyes.

An economic bubble? What’s that?

An economic bubble is a buying cycle with a steep price rise followed by a similarly vertical drop. Many such bubbles are boosted by speculators—investors who believe the price will continue to rise and who want to turn a quick profit. Typically, the buying behaviour is best described as frenzied. When the price is so high that buying slows and stops, the price drops and the bubble bursts. An equally frenzied sell-off then follows as speculators scramble to salvage what profit—if any—they can.

Broadly speaking, a bubble has five stages:

- Interest: A new technology or buying opportunity catches the attention of investors.

- Growth: Investors begin to buy, pushing the price up and creating even more interest.

- Intoxication: Optimism reigns. Prices skyrocket. FOMO (fear of missing out) takes hold.

- Profit: Nervous—or shrewd—investors begin to sell and take their profits out.

- Panic: The price drops. Investors scramble to sell. The bubble bursts. The price crashes.

We can see this familiar cycle appear throughout our economic history.

Human nature is a feature of the economy

There is more than a dash of human psychology in every economic bubble. In his wonderfully titled 1841 book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Charles Mackay explored the psychology behind mass belief and gullibility. One of his interests was market speculation or what he called “money mania.”

Every age has its peculiar folly: Some scheme, project, or fantasy into which it plunges, spurred on by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the force of imitation.

Charles Mackay, poet and social scientist, made an early study of the psychology of crowds and popular myth. He was a debunker of such things as ghosts, alchemy and fortune telling. Image: Wikimedia, the Gutenberg Project

Mackay cited three historic economic bubbles to illustrate his money mania theories.

Tulip Mania: The Netherlands, 1634–37

Artist Jan Brueghel the Younger painted a satire on tulip mania around 1640. It’s worth looking at closely to see what the monkeys are up to. Image: Frans Hals Museum

During the early 17th century, the Dutch fondness for tulips became something of an obsession. The prices at tulip markets rose to ridiculous levels as more and more people bought tulip bulbs in the hope of turning a fast profit. It was the first documented speculative bubble. When the bubble burst, the price of certain bulb types fell from that of a fine Amsterdam house to that of an onion.

The South Sea Bubble: England, 1719–20

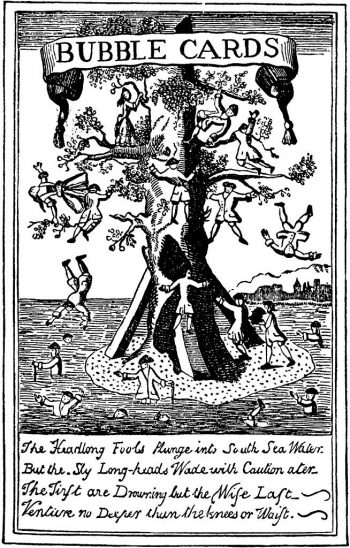

“The headlong fools plunge into South Sea Water. But the sly long-heads wade with caution after.” An illustration from Mackay’s book. Image: Wikimedia, from Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

The South Sea Company was a joint-stock company, one that sells shares in its business to raise money. Its aim was to take over England’s massive public debt and pay it off by selling shares. To provide the necessary boost in stock prices, the company led investors to believe it had a monopoly in South American trade. Investors clamoured to buy the stock, and the value rose by 800 per cent in 8 months. The company really did have a monopoly, but there was no trade. And the bubble burst.

The Mississippi Bubble: France, 1718-20

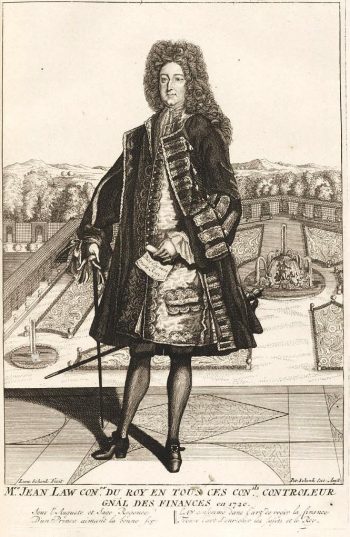

John Law enacted many of his pet economic theories, some very advanced, on the French economy. At heart a gambler and a scoundrel, he created corruption and chaos that would take generations to untangle. Image: Wikimedia, Beineckie Library, Yale University

John Law, a Scottish renegade financier, gambler and convicted murderer, became the French government’s financial advisor in 1715. He established a central bank, issued bank notes and secured a monopoly over development in France’s American territories. Investors became desperate for a piece of this lucrative pie, and prices rocketed. Alas, Law’s promises were empty. The stocks crashed and so did France’s economy.

E-Bubbles, 2017-18

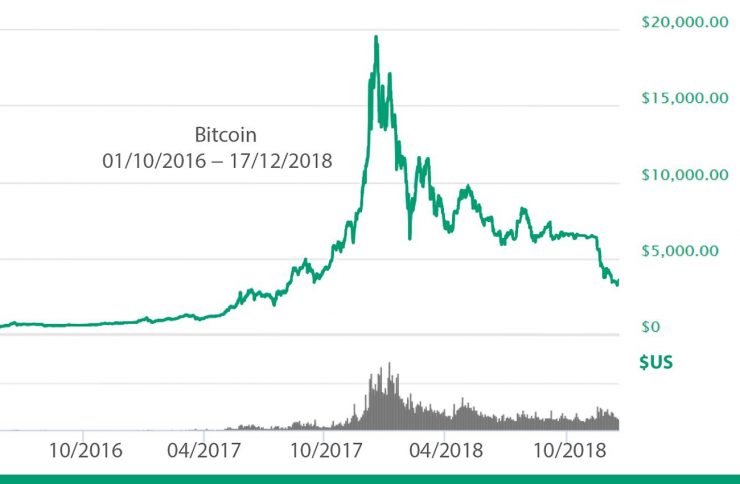

The seemingly modest price spikes following Bitcoin’s epic 2017 peak are actually explosive changes of as much as 200%. Image: Wikimedia, coinmarketcap.com

Speculative bubbles are still with us today. Beginning in early 2017, a buying mania swept the Bitcoin market. From January to November, the price rose from US$1,100 to $6,700. Major investment firms created new Bitcoin investment opportunities and wildly optimistic predictions were made by highly influential people—all pitching buckets of gasoline onto a raging bonfire.

Bitcoin is now at $16,600.00. Those of you in the old school who believe this is a bubble simply have not understood the new mathematics of the Blockchain, or you did not care enough to try. Bubbles are mathematically impossible in this new paradigm. So are corrections and all else.

Tweet: John McAfee, founder of computer security firm McAfee LLC, December 7, 2017.

The price rose in a near-vertical climb, hitting US$20,000 on December 18. Then, with a very loud “pop,” came an equally spirited decline. One volatile year later, the price was around $3,600—a loss in value of roughly 80 per cent. But that price is still around three times what it was in 2016. So, the bubble never entirely deflated, and long-term holders of Bitcoin are still ahead.

Bubble watching

Many people have referred to the recent steep rise in house prices in Vancouver and Toronto as a bubble. While it’s true this currently overheated housing market shows many hallmarks of an economic bubble, it also has a very rational basis: there are simply not enough houses for the people who want them. Several factors have contributed to this rise, including speculation and low interest rates. Borrowing rates have been kept necessarily low in the years following the global financial crisis to stimulate a slow economy, but have had the side effect of heating up the housing market.

Keeping inflation low, stable and predictable preserves the value of money, but central banks such as the Bank of Canada also work to promote a stable and efficient financial system. The Bank pays careful attention to how interest rate adjustments work their way through the economy so that bubbles have a chance to deflate gradually rather than burst.

But as always, “caveat emptor”: let the buyer beware.

Resources and further reading

- G. Davies, A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002)

- N. Ferguson, The Ascent of Money (New York: Penguin, 2008)

- M. Goodwin and D. E. Burr, Economix: How Our Economy Works (and Doesn’t Work) (New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2012)

- “What is a Bubble” (Investopedia, Available at https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bubble.asp)

- T. Lane, “Monetary Policy and Financial Stability—Looking for the Right Tools”(speech to HEC Montréal, Montréal, Quebec, February 8, 2016)

- T. Lane, “Decrypting ‘Crypto’” (speech to Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, October 1, 2018)

- N. Smith, “Yep, Bitcoin Was a Bubble. And It Popped.” (Bloomberg, December 11, 2018. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-12-11/yep-bitcoin-was-a-bubble-and-it-popped)

- C. A. Wilkins, “The Age of Leverage” (speech to the UBC Vancouver School of Economics and CFA Society Vancouver, Vancouver, British Columbia, March 14, 2019)

The Museum Blog

Notes from the Collection: Moving Forward

By: Raewyn Passmore

Notes from the Collection: A Buying Trip to Toronto

By: Paul S. Berry

Director’s chair : A little help from our friends

By: Ken Ross

The Cases are Almost Empty

By: Graham Iddon

Curators Begin Removal of Artifacts

By: Graham Iddon

Notes from the Collection : 2013 RCNA Convention Winnipeg

By: David Bergeron