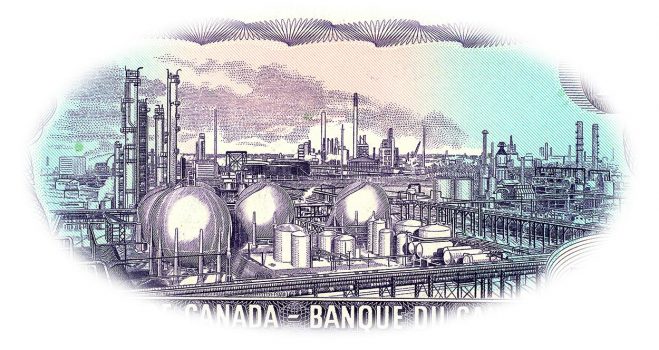

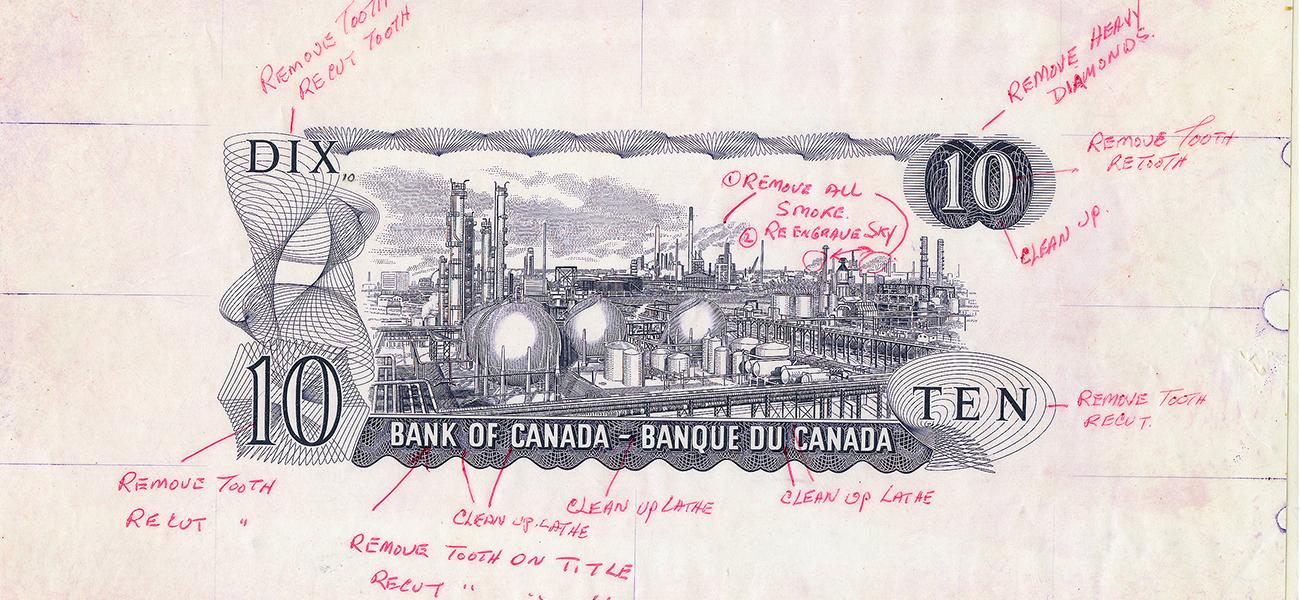

The Scenes of Canada $10 bill

The Scenes of Canada bank note series of the 1970s and 1980s was themed loosely on landscapes with an element of human activity. But the scene on the $10 note was purely industrial—perhaps the last such image we’ll see on our money.

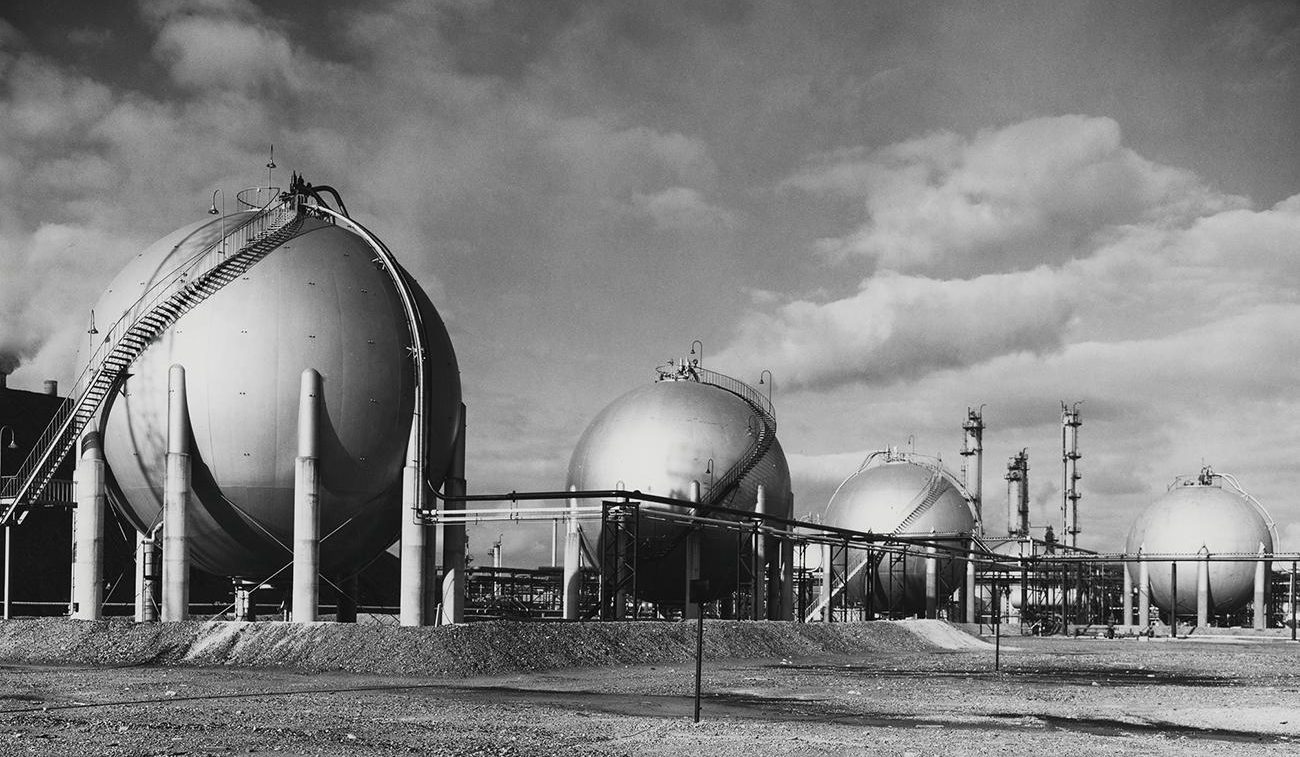

This engraving of the Polymer Corporation plant in Sarnia, Ontario, was derived from a photograph by George Hunter, who also provided the photo used for the $5 bill of this series.

Source: 10 dollars, Canada, 1971 | NCC 1971.256.1

Where there’s smoke, there’s progress

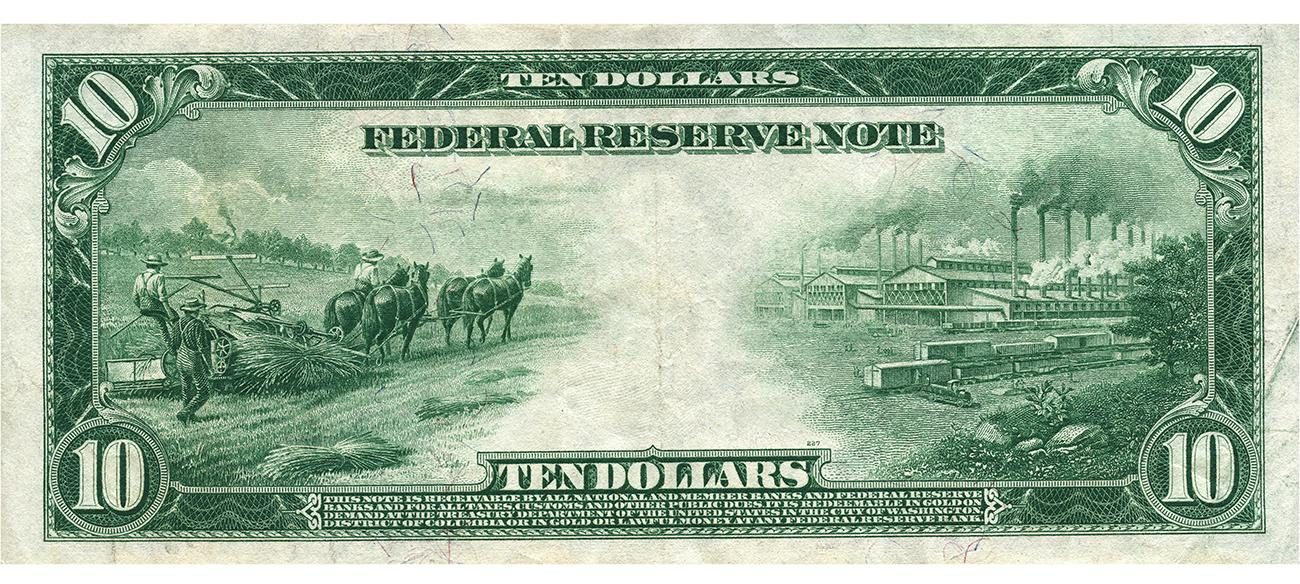

From the late 19th until the early 20th century, “progress” for a nation meant flourishing industry. Nations eager to promote their modernity often did so on their bank notes and stamps. Sometimes these featured sprawling factories, speeding locomotives, industrious steam tractors or vast ocean liners. One thing common to many of these images was smoke—and lots of it.

A little over a 100 years ago, nothing seemed to better characterize an economy at full throttle than forests of belching smokestacks. Industrial cities of the era were horribly polluted, largely from burning coal. Yet images of dense clouds of smoke rolling out of factory chimneys were thought to express positive messages of economic growth and modernity. If nothing else, a thick industrial cloud certainly added atmosphere to an engraving.

A re-imagined vision of Canada

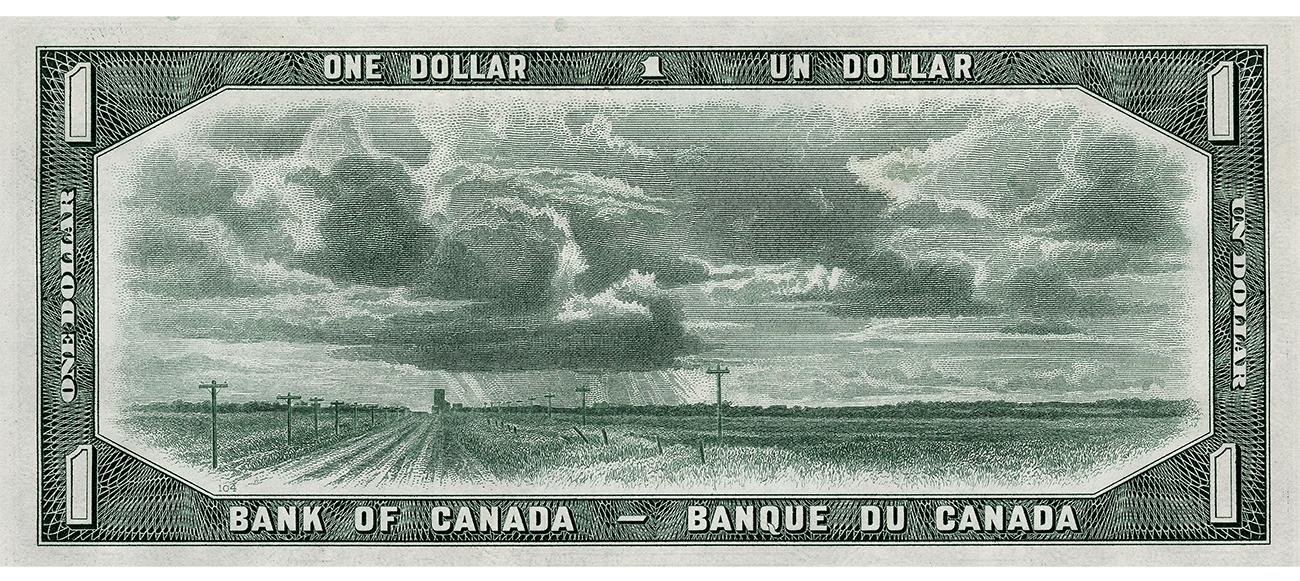

At least on its government bank notes, Canada rarely promoted an industrialized image of itself. It tended to highlight its resource extraction rather than its much younger production industries. After the Second World War, such images disappeared completely, to be replaced by pristine landscapes with very limited signs of humanity: the 1954 Canadian Landscape series.

For the Scenes of Canada series, the Bank expanded on the landscape theme, adding a greater presence of people: Canadians at work on the land. For the most part, these images showed traditional, and somewhat nostalgic, Canadian views: fishing, hunting, logging, Mounties, a historic seaport, mountains, a petrochemical plant. Wait, what was that last one?

Though it was part of the 1954 Canadian Landscape series, this prairie view of farmed fields actually presents a landscape substantially altered by human activities.

Source: 1 dollar, Canada, 1954 | NCC 1965.43.1

The engineered landscape

Choosing such an image was as much about counterfeit prevention as it was about the message the image conveyed. A Bank memo stated, “[it] provided detail ideally suited to engraving.” A petrochemical plant certainly provides an opportunity for some really fabulous engraving. Its extraordinary detail would be a challenge for the most accomplished of engravers—from either side of the law.

Of course, choosing an industrial facility for a bank note is not a casual decision. At the end of the 1960s, such places were earning a bad reputation for pollution. An industrial plant is not as uplifting as an awesome range of mountain peaks, so there must have been a good reason for choosing such a scene. There was, actually, but it may not have been obvious to many Canadians.

The war in the Pacific comes to Canada

This $10 bill’s message was really about achievement during war—but not in battle.

War creates a great need for all sorts of materials, and a nation’s response can mean the difference between victory and defeat. The creation of the Polymer Corporation near Sarnia, Ontario, was just such a response. But the provocation was 8,000 kilometres away.

Japan’s 1941 attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, was only one part of a coordinated attack on targets from Singapore to Hong Kong. Almost overnight, Imperial Japan had gained control of much of Southeast Asia, which included 90 percent of the world’s supply of natural rubber. And without reliable access to rubber, the Allied war machine would (literally) grind to a halt. For want of a tire, the war could be lost.

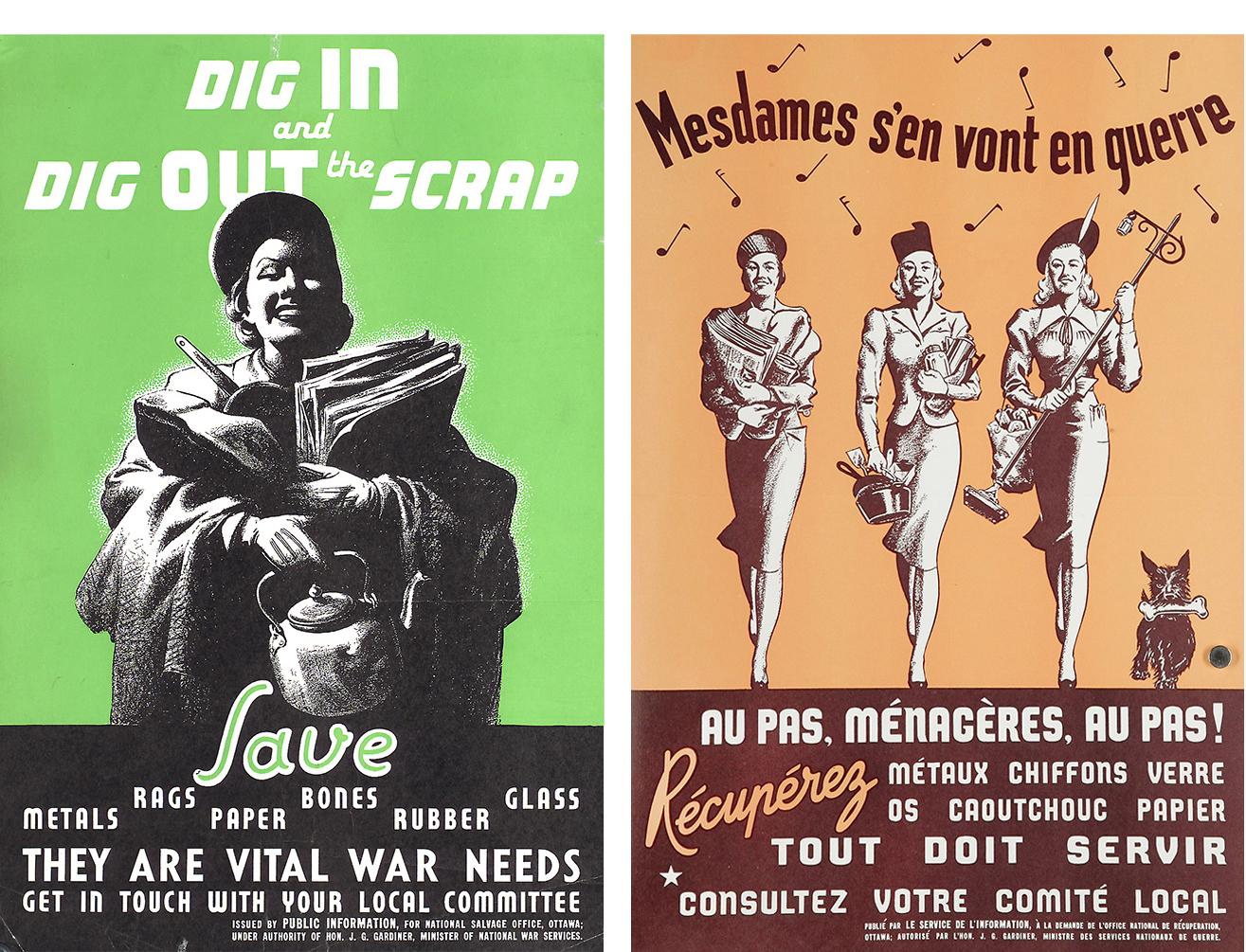

In 1941, the National Salvage Office launched a campaign encouraging Canadians to collect scrap materials for war production. The loss of rubber sources alone was considered a national emergency, and salvage was a major war effort.

Source: posters, National Salvage Office, 1940–41, (left) courtesy Toronto Public Library | (right) Canadian War Museum, 20010129-0503

On the heels of Pearl Harbour, Canada’s Minister of Munitions and Supply, C. D. Howe, authorized a very bold proposal: to make synthetic rubber in Canada. It was very risky. Scientists had known how to produce synthetic rubber since the 1880s but only in modest quantities. So complicated was the process that it had never been done on an industrial scale, at least not in the United States and Canada. At the outbreak of war, less than 1 percent of North America’s rubber supply was synthetic.

Planning began in January 1942, and a site near Sarnia was selected. Sarnia had a number of advantages. It was close to:

- major transportation routes

- petroleum supplies

- plenty of water

- industries that produced rubber products.

Amazingly, the plant began operating after only one year. It was expanded in 1944.

Polymer Corporation managed to produce more than 4,000 tonnes of rubber per month for the Canadian and US war effort as well as for domestic consumption. Such an enormous achievement went a long way to ensuring an Allied victory. And this achievement goes a long way to explain why a petrochemical plant was a fitting image for a Canadian bank note.

In a way, the 1971 $10 bill foreshadowed our Frontiers series bank notes. It may be the last time we see industry on a bank note, but it was not the last time the message would be about Canadian achievement.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.