For centuries, people have added alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection.

The love token: a numismatic definition

A love token is a coin that has been smoothed flat on at least one side and then re-engraved with a new message. To fully qualify, it should originally have been an officially-issued, circulating coin or token—and re-worked by hand. Unlike one altered for political or advertising purposes, a coin transformed into a love token is a gift that usually does not go back into circulation.

Despite the name, not all love tokens are expressions of love. The genre also includes commemorations of important occasions, such as births, marriages and life-changing events. These pieces are really mementos but are nevertheless referred to as love tokens.

Rooted in ancient ritual

The roots of the love token may be found in the historic association money has with luck—as a medium able to carry and transfer it. From the earliest days of money, people have used coins ritually, as offerings to the gods or to ancestors to obtain good fortune for themselves or others. Remnants of these practices can still be seen scattered on the bottoms of fountains and decorative pools. Grooms have also given coins to their brides at weddings as symbols of togetherness, commitment, love and contractual obligation.

It was once believed that a monarch had the God-given ability to heal the sick by touching them. Touch pieces are coins handled by such a monarch. They were pressed or worn against the bodies of the sick in the hope of being cured.

Source: 10 shillings (1 angel), touch piece, Charles I, England, 1632 | 2019.6.1

Although many varieties of love tokens have been around since Roman times, the earliest common use of coin-based love tokens emerged in 13th century England. They were not usually engraved with messages but were simply coins bent into a wave shape. Sometimes called “benders,” they were often given by men to women they were attracted to. The coins acted as symbols of both love and intent. Bending the coin prevented it from being spent and identified it as symbolic and not practical. Sometimes the coin was pierced and worn on the body, maybe next to the wearer’s heart.

To be clear, defacing any government-issued currency has been—and remains—illegal in most countries. Still, that never stopped an ardent lover…

Romantic Victorians (and Edwardians)

Stereotypically speaking, the Victorians were a sentimental lot. But by the mid-19th century, the popularity of love tokens had already begun to wane in Great Britain—just when they were beginning to peak in North America. Most love tokens in the Bank of Canada Museum’s Collection are from this era and the early 20th century. Our most recently-made love tokens are from the 1930s.

Like most of the love tokens in our Collection, this one was likely engraved by an amateur with a bit of talent. The new profile is carefully worked into the existing effigy of King George V as if the man with the pipe were the king.

Source: love token, Canada, early 20th century / 1 cent, Canada, 1920 | 1977.22.7

Silver coins were a popular choice for Victorian love tokens. Silver is beautiful and soft enough to be easily worked by hand. Also, coins such as US silver dollars and British crowns of that era were quite large, leaving lots of working space. The messages on love tokens were chiefly the initials or names of sweethearts. Memento tokens were more likely to have content beyond initials such as dates, locations and images. It’s not uncommon to find love tokens with eyelets, piercings or pins attached—the better to show off your love token. And they weren’t necessarily made from local coins, either. Canadian love tokens have been based on coins from all over Europe and even Egypt.

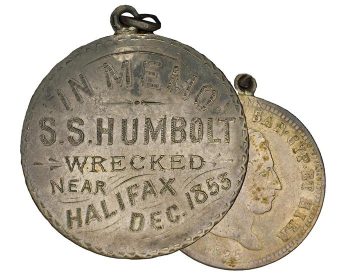

The S.S. Humboldt was an American steamship that struck shoals as it approached the entrance to Halifax Harbour in heavy fog. The inscription on this memorial love token reads: “IN MEMO S.S. HUMBOLT WRECKED NEAR HALIFAX DEC 1853.”

Source: souvenir love token, Canada, 1853 / 2 lire, Sardinia, 1825. | 1971.29.5

An important qualification of a true love token was (and still is) that it be made by hand. Several methods may have been employed such as engraving, stamping or pin-punching. In this last method, the new images and words were made up of tiny dimples punched into the surface of the coin with a nail or other sharp point. Regardless of the method, the process nearly always began by rubbing out the original coin design using a tool or an abrasive material and then smoothing the surface to prepare a clear working space.

A First World War soldier named

Edward Atkinson created the message on this memorial love token by tapping a sharp point into the surface of the coin to build letters and shapes.

Source: love token, Edward Atkinson, Canada, around 1919 / 5 lire, Italy, 1861–78 | 1972.49.6

Convict tokens

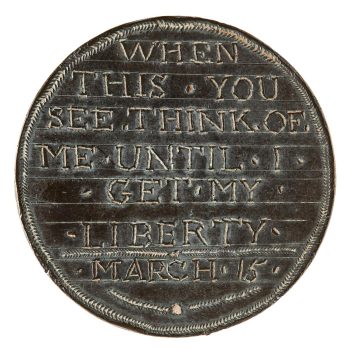

“WHEN THIS YOU SEE THINK OF ME UNTIL I GET MY LIBERTY MARCH 15.” “When this you see think of me…” was a popular phrase on convict tokens. It’s commonly found in sailors’ farewells, messages given by mariners to loved ones before disappearing on long voyages.

Source: convict token, T. Lucas, United Kingdom, 1834 | National Museum of Australia 2008.39.158

From 1788 to 1868, roughly 160,000 British and Irish convicts were sentenced to be “transported” to Australia. Transportation, as it was called, served the dual purpose of relieving overcrowded British jails and populating a distant colony. For most convicts, it was an acceptable alternative to years in a miserable jail or execution—and even thieves were executed at that time. Transportation was no picnic, however, and was in many cases a death sentence. Few who completed their prison terms had the wherewithal to come back. A sentence of just a few years usually resulted in a permanent move to colonial Australia and a complete severance of the convict’s personal relationships. So, love tokens given by convicts served a different purpose than your standard message of love: a heartfelt farewell letter inscribed in metal—a forget-me-not memento. Roughly 20% of today’s settler Australians are descendants of transported convicts.

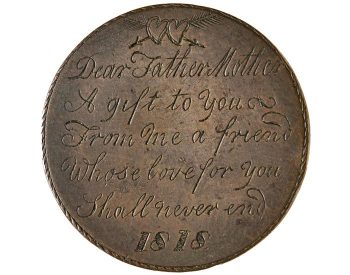

“Dear Father Mother a gift to you from me a friend whose love for you shall never end 1818,” wrote 15-year-old John Campling before being shipped to Australia for stealing a watch. He may have paid somebody to make this elegant token.

Source: convict token, John Campling, United Kingdom, 1818 | National Museum of Australia 2008.39.26

Convict tokens were usually made from copper coins. It’s a simple case of the economics of the under classes. During the late 18th century, the most common coins used were “coppers.” Strictly speaking, these were themselves tokens, not coins, issued by merchants as small change. The Royal Mint began issuing copper pennies in 1797. At 36 mm across and 3 mm thick, these “cartwheel pennies” were enormous and became the medium of choice for convict tokens.

A love token show

The Museum has hundreds of love tokens in its vaults. They run the gamut from crudely scrawled inscriptions to elaborate productions of flourishes and gloriously overblown lettering. Though the sentiment is often the same, each love token is unique.

Tokens of modern love

Love tokens are still made today. But like everything else, they have become more sophisticated. Since they are quite private things, we can’t know how many are being made in the traditional manner. But there is a niche market of ready-made ones—just add your message. They may sometimes be jeweled or enameled but are likely no longer made from coins. No matter, modern love tokens still carry the same messages for the same reasons.

Because people—and their feelings of love and affection—don’t change.

A popular form of modern love token is the love lock. The names or initials of both halves of the relationship are inscribed on a padlock, which is then locked to a fence or a bridge. There are hundreds of love locks on the Corktown Bridge over the Rideau Canal in Ottawa.

Source: photo: Joanne Clifford, Wikimedia Commons

The Museum Blog

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.