Apart from commemorative designs, the reverse sides (tails) of our pocket change have remained the same since 1937. Or have they?

A parade of sovereigns on the obverses of the coat of arms 50-cent piece. The various portraits of Queen Elizabeth II are named “Laureate,” “Tiara,” “Diadem” and “Uncrowned.”

Source: 50 cents, Canada, 1937, 1959, 1965, 1997, 2003, 2023 | 1969.156.3.5, 1978.58.413.5, 1965.141.5, 2002.73.25, 2009.56.18, 2024.5.13

First, the small changes in our small change

Since 1937, the only real changes that have occurred to the tails sides of our coins are the dates. For many years, only the first three numbers of the dates were on the master coin dies, and the final numbers were added to the production die by hand. This resulted in a few unplanned variations that take a pretty sharp and educated eye to spot. For the vast majority of us, the designs introduced in the late 1930s—the maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous—appeared unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms changed, so did the coin.

Canada’s less-than-simple heraldry

We have to step sideways for a bit and talk about the Coat of Arms of Canada and heraldry in general.

First off, arms are symbols used to represent a person, family, organization, city, province, nation—even a corporation. They could be animals, shields, flowers, flags, weapons, etc. A coat of arms is the whole deal: crests, animals, flags, helmets and plants together in one complicated symbol.

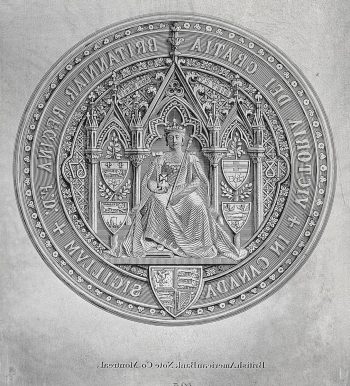

Just after Confederation, Queen Victoria granted the right to create official arms to the four founding provinces: Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. She also decreed that the four arms should be integrated into the Great Seal of Canada, a design that was embossed on documents to mark them as officially authorized. But there was still no official coat of arms for the Dominion of Canada.

During the First World War, a serious and contentious effort was begun to create an official coat of arms for Canada. Not officially authorized until 1921, the final version carried symbols of France, England, Ireland and Scotland but without even a whiff of Indigenous presence (though the idea was discussed). The design closely resembled the British coat of arms, but with a major departure: a branch of three maple leaves.

Arms on money

This is the first use of what appears to be a coat of arms on a Canadian government bank note—but at that time there was no Canadian coat of arms. The Coat of Arms of Canada was first printed on the 1954 series of notes and every note through the Canadian Journey series. It has since reappeared on the Vertical 10.

Source: 2 dollars, Dominion of Canada, 1914 | 1964.88.882

In the late 1930s, with the crowning of the United Kingdom’s King Edward VIII, Canada (along with several other Commonwealth nations) decided the time was ripe for modern and more relevant coin designs. The subject of the 50-cent piece was the first of the new series to be approved—in July 1936. However, the coin pattern differed substantially from the official coat of arms. Designer George Kruger Gray did not include the helmet or flourishes, the lion, the floral elements or the ribbon carrying “A MARI USQUE AD MARE” (from sea to sea). But he enlarged the crown and created more breathing space around the items in the shield. The result was a bigger, simpler and far clearer version of the arms than would later appear on the 50-cent pieces. Those designs would be faithful to the official symbol.

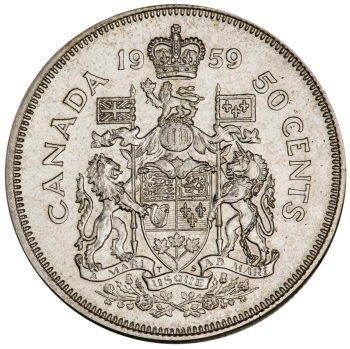

1959: redesigned arms, redesigned coin

In the late 1950s, the Coat of Arms of Canada was simplified, and a few details were changed. It was redrawn by artist Alan Beddoe, a historian, archivist and founder of the Heraldry Society of Canada. He changed the crown from a Tudor design to the St. Edward’s Crown, as used by Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III in their coronations. He also greatly simplified the flowers along the bottom and toned down the rather exuberant flourishes around the helmet. Apart from the leaves, the shield was still basically a version of the British crest.

With a changed coat of arms came a changed 50-cent piece, including a new design by the Mint’s head engraver, Thomas Shingles. And an astonishingly detailed coin it was. Though a small and fussy design, it was far more faithful to the official heraldry than the original coin was.

1997: a more Canadian coat of arms

For nearly 40 years, the coat of arms on the 50-cent piece went largely unchanged, with the occasional tiny adjustments to improve the life of the stamping dies. There was a slight shrinking of the entire coin in 1968 with the transition from silver to nickel. However, after the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was enshrined in our constitution in 1982, many felt that the coat of arms needed to be updated again. They wanted to see Canada’s highest honour, the Order of Canada, incorporated into the arms, much like the United Kingdom’s Order of the Garter is represented on theirs. Cathy Bursey-Sabourin designed the new arms in the late 1980s. It finally received Royal approval in 1994.

And so, the 50-cent piece changed again to match a new interpretation of our arms—right down to the outlines and flowers. Throughout the first decades of the new millennium, the coat of arms on the 50-cent coin has remained as it was in 1994, despite the addition of commemorative dates or the moving of the legend to the back for some special releases. There has simply been no need to change it.

A Coat of Arms of the future?

In June 2008, Patrick Martin, the Member of Parliament for Winnipeg Centre, forwarded a motion in the House of Commons requiring a change to the coat of arms. Martin was calling for the inclusion of symbols representing Inuit, Métis and First Nations peoples in Canada’s heraldry, a suggestion first made by heraldry designer Edward Chadwick in 1917. (Another Winnipeg MP, Robert-Falcon Oullette, called for the same action in 2019.) Suggestions for changes included making the supporting animals Canadian or adding another sea to the motto to include the Arctic coast.

Whatever happens to the Coat of Arms of Canada, the 50-cent piece would likely follow suit.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.