Creating a simple explanation for the gold standard is itself far from simple. The basic theory is easy to describe, but how the gold standard evolved and functioned in modern, complex economies is not.

A perfect gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by the authority that issued it. And each note can be exchanged for its value in gold. That’s it—a fairly simple system.

But the gold standard’s basic rules would be repeatedly bent in the face of modern economic realities.

An ideal gold standard existed briefly in 17th century England—not with banks as we know them, but with goldsmiths (artisans who worked with gold). If you were a rich 17th century Londoner, you might’ve stored your gold in a goldsmith’s vault. If you wanted to make a major purchase, you would have to take a heavy sack of gold out of the vault and lug it through streets crawling with every sort of rogue and scallywag.

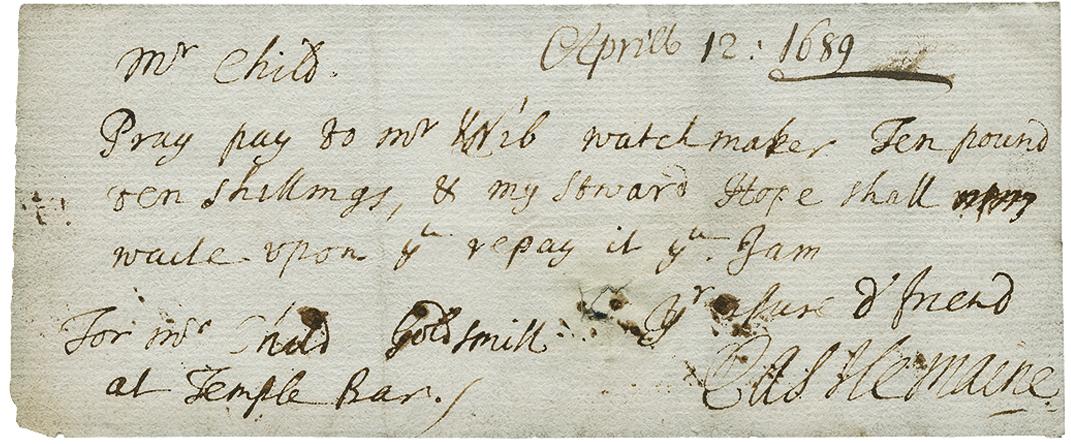

But your goldsmith might have offered an attractive alternative: an official receipt for a specific amount of the gold you have stored in their vault. It began as mere convenience, but with time, those notes became transferable. People could trade the note for items or services—and the recipient of the note could then do the same. The gold stayed put, but its tradable value circulated in the economy like a $20 bill does today. As casual as they seem, goldsmith notes, like the one below, are considered the root of bank notes in England and, by extension, the United States and Canada.

"Pray pay to Mr. Knib watchmaker 10 pound ten shillings…” ($2,400 today). This goldsmith note asks Sir Francis Child, goldsmith, to pay a bill for Robert Palmer, 1st Earl of Castlemaine, by transferring an amount of gold to a watchmaker.

Source: 10 pounds & 10 shillings, goldsmith note, Robert Palmer, United Kingdom, 1689 | NCC 1963.48.40

Goldsmiths would later take on the role of modern bankers, offering loans and bills of exchange (an early form of today’s cheques). With such convenience available, why would you remove your gold from the vault? Goldsmiths soon recognized that they could (figuratively and literally) make money by issuing more notes than the amount of gold they were holding—usually in the form of loans. After all, not everybody would attempt to withdraw their gold at the same time. And that assumption forms the basis of the gold standard as it was practised well into the 20th century.

The trouble with gold

For centuries, a gold coin could be used anywhere no matter who issued it, as long as its purity was trusted. Well into modern history, all you had to do was weigh a gold coin to know what it could buy in your area and at that time. And that was the problem with gold—the trading value of gold coins was constantly changing because it was tied to the market value of gold itself.

If a British 1-guinea gold coin weighed less than this official test weight, either bits of it had been shaved off (called clipping) or the coin was very worn. It might also mean the coin was counterfeit. Regardless, it was no longer worth its official value.

Source: 1 guinea, coin weight, Great Britain, 1772 | NCC 2013.2.971; 1 guinea, Great Britain, 1769 | NCC 1973.90.1

Gold’s ever-shifting market value made using it to back paper money seriously problematic—so much so that it was sometimes necessary for authorities to legally set the price of gold to stabilize a nation’s currency. This happened during the Great Depression when the United Kingdom went off the gold standard in 1931, raising fears that the United States would do the same. Foreign holders of US currency got nervous and attempted to exchange their cash for gold in an effort to secure their investment. Desperate to stop the flow of gold from going to foreign investors, US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt changed the value of gold from $20 to $35 an ounce in 1934 and outlawed private ownership of bullion. At the same time, the US Federal Reserve Bank raised interest rates. The value of the US dollar rose, encouraging investors to keep their US currency. These interventions stabilized the gold reserves and the value of the currency—all to maintain a system that could be seen as bit of a charade. A charade because an ideal gold standard has never functioned in a modern economy—there has always been far more cash value in circulation than gold value to support it.

The economy: A tree that must continue to grow to survive

For an economy to grow, its money supply needs to grow along with it. Under a gold standard, there would therefore be a constant demand for more and more gold. But there is only so much gold in the world, both discovered and undiscovered. This would certainly keep inflation in check, but it would also keep economic growth in check—or strangle it, depending on your point of view.

Piracy was also a way to get gold into the economy. Privateers—pirates authorized by the British government—cruised the Caribbean during wars with Spain, hunting for treasure ships to rob. The Spanish gold doubloon was the great prize, an icon of pirate lore.

Source: 8 escudos, Spain, 1714| NCC 2015.24.1

To allow economic growth, governments and bankers issued more bank notes than could be exchanged for gold. It’s worth noting, though, that notes were also often backed by other things that could be converted to gold, such as government debentures (bonds) and bank notes, bills of exchange or silver coins.

Like goldsmiths 200 years earlier, authorities assumed that few people would demand gold in exchange for their bank notes and the paper money would simply circulate around the economy serving its basic function. And it generally did. This is similar to today’s fractional reserve banking, where only a fraction of depositors’ money is held in an immediately accessible form (cash, nowadays) while the rest is loaned out—again, working on the assumption that few will attempt to withdraw all their money.

Of course, this can get out of hand. For all of banking’s early history, from China to Sweden and France and England, the urge to issue way more notes than there was valuable metal to back them proved to be a temptation far too great. And it backfired for note issuers in all these nations, causing the values of paper money to plummet, public trust to evaporate, and banks to fail.

During a gold and silver shortage, Sweden issued copper coins the size of dinner plates. This currency was so awkward that Sweden’s first bank, the Stockholms Banco, issued paper money to represent this enormous currency—leaving the coins in storage. It went bankrupt in 1667. This plate money pictured here is very similar, though from a later attempt to use copper currency in Sweden.

Source: 1 daler, Sweden, 1746 | NCC 1966.3.5

The standard in good times

The British sovereign and the American eagle were the backbone of the gold standard during its heyday, around the turn of the 20th century. The eagle is more than twice the weight of the sovereign, though they are close to the same diameter.

Source: 1 sovereign, United Kingdom, 1871/10 dollars, United States 1887| NCC 1970.167.14 / NCC 1970.132.11

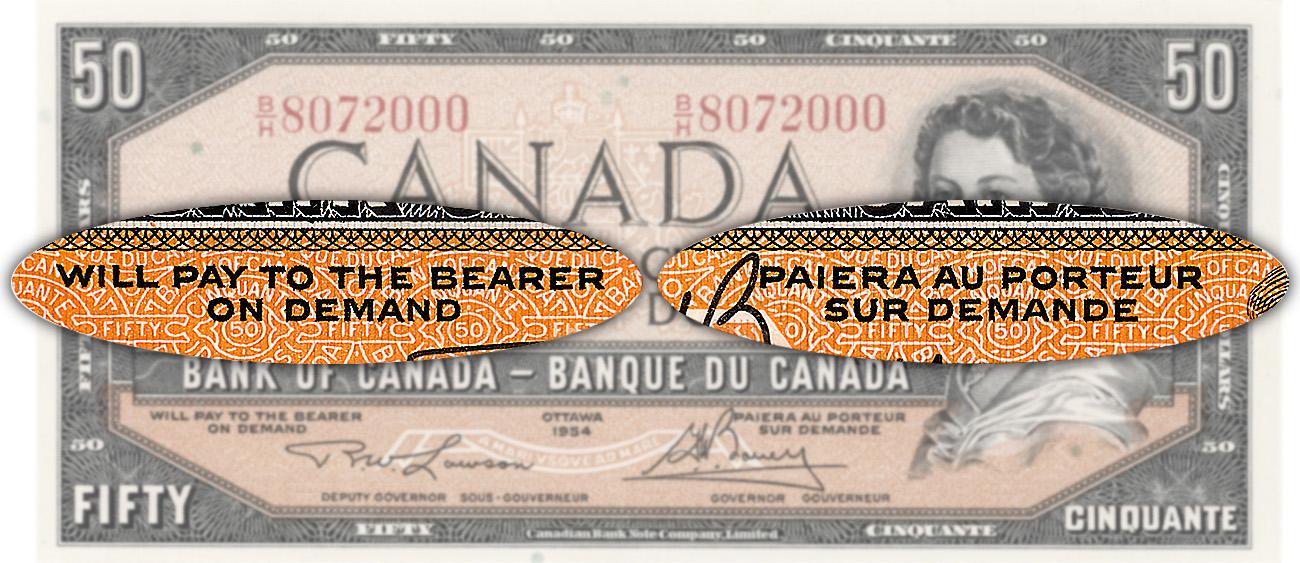

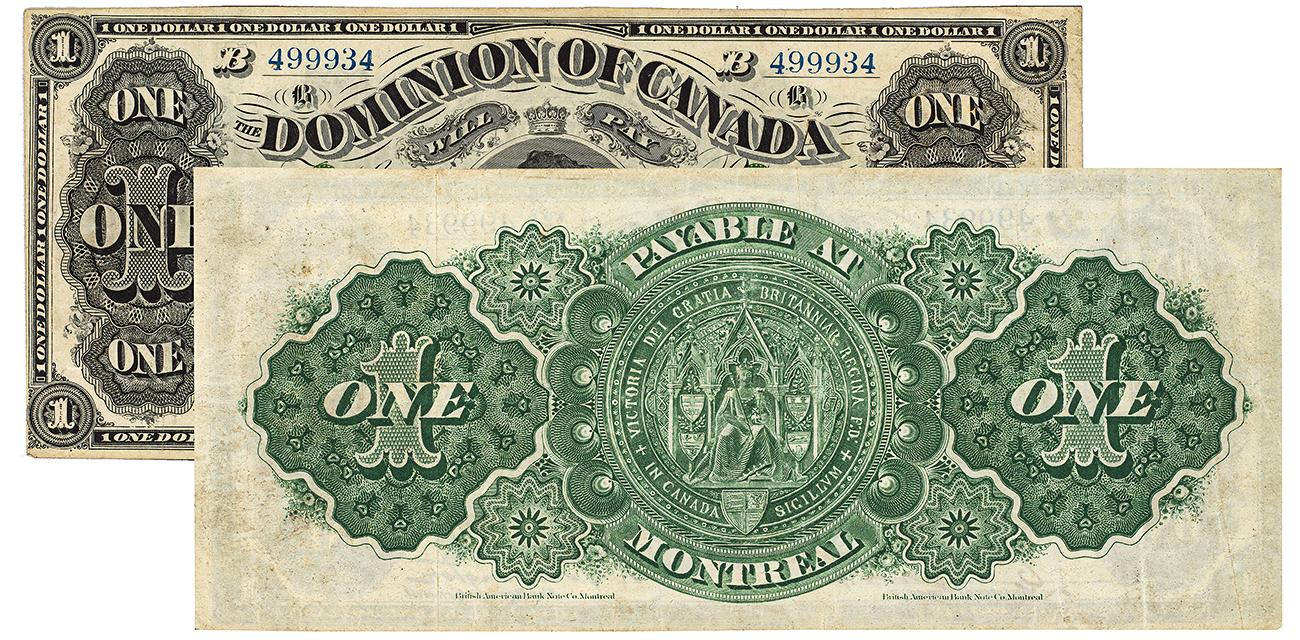

When the world’s leading economies adopted official gold standards in the 19th century, governments required that their currencies be backed by gold reserves equal to a given percentage of the value of the bank notes they issued. In 1868, the Dominion of Canada established a gold reserve requirement valued between 20% and 25% of its notes in circulation. When Canadian commercial banks issued paper money, any of their notes could be exchanged for gold. How the banks linked their notes to gold was their problem, but they could back them with items easily converted into gold, such as silver or, after 1870, Dominion of Canada notes.

Heading into the 20th century, the international gold standard functioned very well—especially in the United Kingdom, which had the most gold in the world. Industry ran at full throttle, and the money flowed freely right up until 1914 when the gold standard ran into a very solid brick wall: the First World War.

The standard in bad times

Capitalists, governments and bankers might’ve defended the gold standard to the death in peaceful times, but as soon as war was declared, many countries had to quickly suspended it. The First World War had barely begun when the British and Canadian governments temporarily prohibited citizens from exchanging bank notes for gold. This was abandoning the gold standard in all but name, which governments chose to do because they knew there was no way a war of that magnitude could be financed under a restrictive system such as the gold standard. The same thing had happened at the outset of the US Civil War.

The greenback was money issued by the US government to pay for its efforts during the US Civil War. It had no backing beyond a government guarantee of value. It circulated but resulted in inflation. The US went back to the gold standard in 1879.

Source: 1 dollar, United States, 1862 | NCC 1966.98.2424

The Great Depression, however, was a different story. At first, the economic tactics of the First World War were not applied to this particular catastrophe. At the start of that war, the Canadian government knew it was about to face a need for a staggering amount of money. The idea of a government spending its way out of a depression, however, was still a foreign notion to all but advanced economic thinkers. And unlike at the beginning of the First World War in 1914, at the start of the Great Depression in 1929, governments didn’t foresee an immediate need for large sums of money. But that soon changed.

In 1931, exporting gold from Canada was prohibited. As well, banks and the government together persuaded citizens to refrain from exchanging their cash for gold. It was promoted as a patriotic duty, but its main purpose was to protect gold reserves to prop up unstable banks. Nobody said it out loud, but Canada had once again gone off the gold standard. The United States went off it that same year as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” economic recovery plan. Both countries stayed off the standard until after the Second World War.

The post-war fate of the gold standard

As the Second World War ended, 44 nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to establish the post-war economic relations of Western countries. The Bretton Woods Agreement pegged currencies of the participating nations to the US dollar, which would, in turn, be backed by the United States’ enormous holdings of gold. The gold-backed US dollar offered needed stability to the unstable currencies of countries in economic ruin, flattening the playing field for international exchange rates. This avoided the sort of instability, inflation and social unrest that plagued Europe following the First World War—all of which led, ultimately, to the Second World War. Citizens still couldn’t exchange their bank notes for gold, but this was the gold standard in a broad form.

But as Europe rose from the rubble, the gold backing that had provided stability began to choke economic expansion. In the decades that followed, one country after another left the Bretton Woods Agreement. Meanwhile, the United States continued to maintain the gold standard—in varying degrees—until leaving it for good in 1971. Canada was on and off the standard in the 1950s and 1960s, finally going off forever in 1970.

The African standard

In April 2024, Zimbabwe introduced a gold-backed currency called the ZiG—the only such currency in the world today. It was designed to stabilize the nation’s sky-high inflation and move Zimbabweans away from using US dollars as their trusted currency. After several months, it hadn’t managed to do either—the public had too much trust in the US dollar and not enough in its government currencies. At the end of September 2024, Zimbabwe’s central bank devalued the ZiG by 43%. The Zimbabwe government is still hopeful the ZiG will push the US dollar out of Zimbabwe’s economy by 2030.

Trust is worth its weight in gold

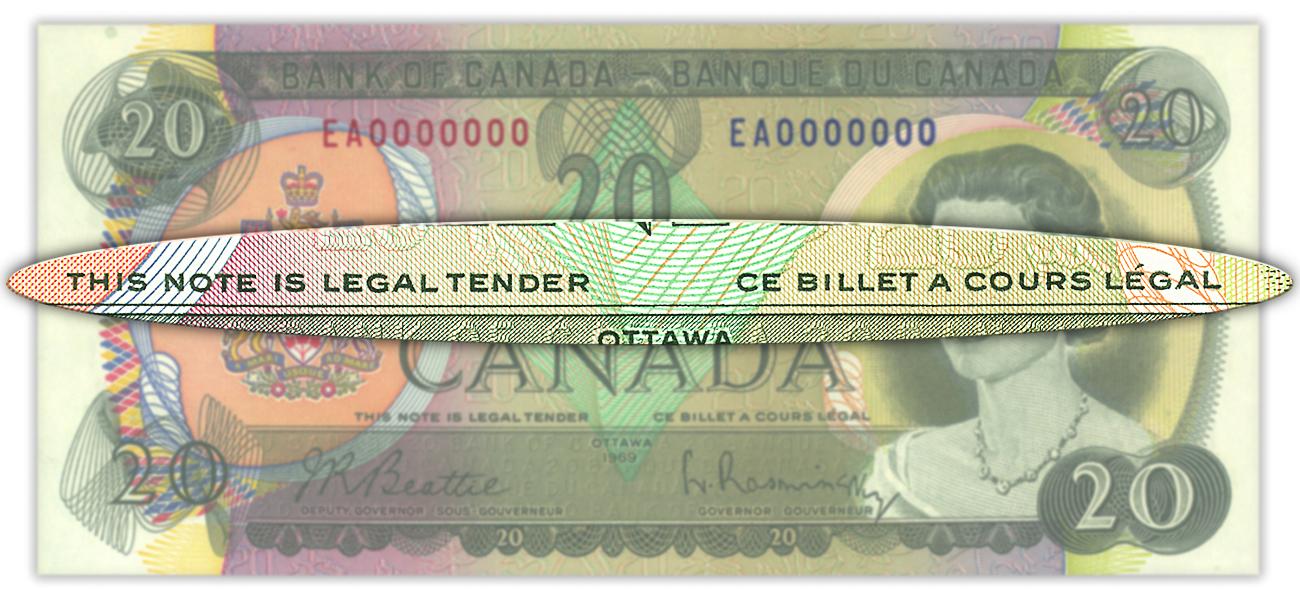

Historically, with the gold standard, prices were rarely any more stable than they were with legal tender. The reality was that only a small percentage of the value of any nation’s currency was ever backed by gold. So little, in fact, that most officially gold-backed bank notes functioned just like Canada’s modern fiat currency—money that circulates with no backing other than a guarantee by a government and oversight by a vigilant central bank.

This highlights the basic function of money: to act as a tradable token representing our skills and time, a token that need not be valuable in itself or exchangeable for precious metal. All it needs is public trust.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.