The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art? Assistant Curator Krista Broeckx talks to Shebageget about the artwork and its relevance to the Museum.

To create Free Ride, Shebageget collected fifty $5 bank notes, one from each year of his life. He arranged them in a grid as a record of his treaty annuity payments. The artwork’s title is engraved repeatedly inside the frame.

Source: Frank Shebageget, Free Ride, framed bank notes, 2022, NCC 2022.36.1

The following interview was conducted at the Bank of Canada Museum on May 1, 2023. It has been edited and condensed for the blog.

Meet the artist

Can you start by introducing yourself?

My name is Frank Shebageget. I am Ojibway Anishinaabe from Northwestern Ontario. I grew up in a small town called Upsala, which is about 100 kilometres west of Thunder Bay. My dad’s reserve, Lac des Milles Lacs First Nation, is close by. And my mother is from Ojibways of Onigaming First Nation, which is closer to the Ontario border with the United States, near Minnesota. I went to the Ontario College of Art and Design and graduated in 1996. Then I went to the University of Victoria for my fine arts master’s degree. My disciplines are sculpture and installation. My work is conceptual, and numbers have an important meaning for me. I like to mix materials together to see how they work with each other to give you a visual history of my culture.

Tell me about Free Ride : how and why did you make the artwork?

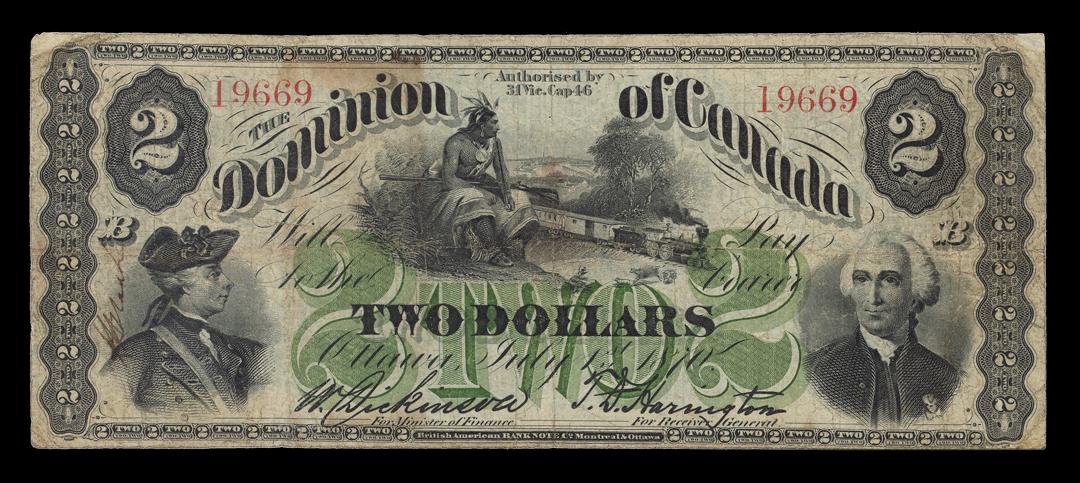

I’ve always wanted to do something with the $5 bill because it has cultural and historical references for me. What you have is fifty $5 bills, which is because I’m 50 years old now. The artwork has to do with the treaty payments that some Indigenous people in Canada get. I’m from Treaty 3, which was signed between First Nations and the Crown in 1873. That’s what the artwork is based on. The whole point of Treaty 3 was that the Crown wanted to have road and waterway access from Fort Garry (now Winnipeg) to Fort William (now Thunder Bay). It was a treaty about goods, land rights, and hunting and fishing rights. As part of the treaty, we get a $5 annuity payment for life. And 150 years later, it’s a contract that’s still being honoured—at least parts of it are.

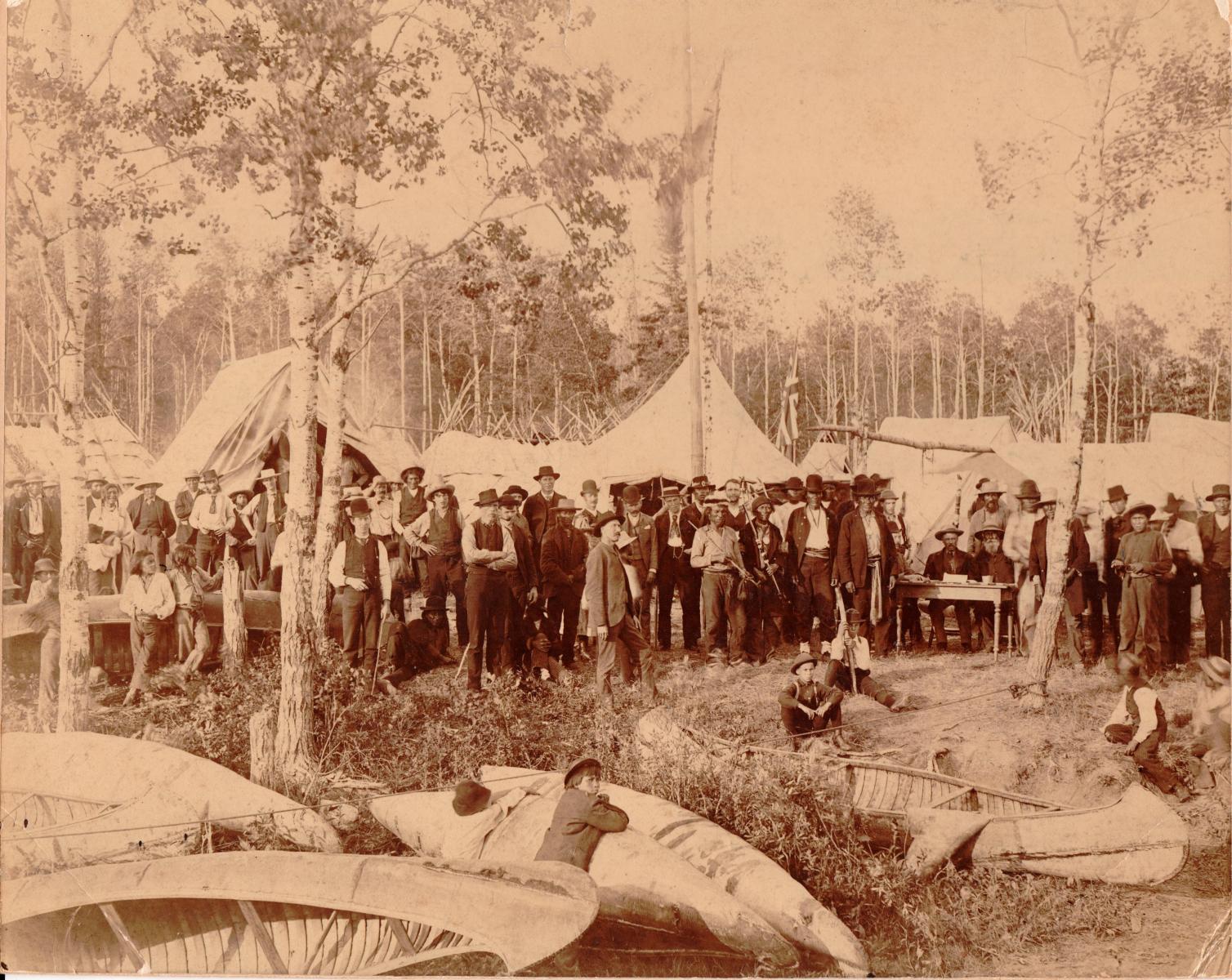

Treaty 3 negotiations took place over three years. The treaty was signed at the Northwest Angle, near Minnesota along the border of Ontario and Manitoba, on October 3, 1873. This photo shows treaty negotiators, some of whom are wearing treaty medals and holding ceremonial pipes.

Source: Wright Bros. Photographers, Rat Portage [Kenora], Ontario, 1873.

Image: Courtesy Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, Manitoba

But Indigenous people deal with racism and stereotypes: some people think that their tax dollars are paying for me—that I get everything for free and that my people have it easy. Yet we face many issues in our communities: poverty is rampant, suicide is rampant, alcoholism is rampant. So the artwork acknowledges that history and layers it with my personal history as well.

How did you come up with the title of the artwork?

The title relates to racism and the stereotypes about Indigenous people. One of the terms that I’ve heard a lot is “free ride.”

I saw—I think it was on social media—someone said Indigenous people get a free ride from the government. It always felt like no one had an accurate understanding of my people, so I was always doing a lot of explaining. For example, if you live on a reserve, you don’t own the land. You don’t even own the house you’re in. Also, a lot of things were illegal back in the day: we couldn’t have a lawyer; we couldn’t have a job off reserve. We couldn’t sell things off reserve. So it was hard for Indigenous people to make a living.

But because of this treaty agreement, I have rights within Canada to do certain things. Maybe that’s part of where all the stereotypes and racism come from. Do those rights get honoured? Sometimes. Most of the time they don’t, but that’s what was agreed upon in the treaty. I went the route of engraving “free ride” within the frame, so the title is part of the artwork. It’s serious, but it kind of pokes fun at things as well. It plays on the idea that the $5 payment is the answer—that it will solve all the problems in our communities.

The title Free Ride is an important part of the artwork. It is engraved twelve times on the inside of the frame, subtly referencing the unfair stereotypes that frame the way many non-Indigenous people understand the treaties.

Source: Detail of Frank Shebageget, Free Ride, framed bank notes, 2022, NCC 2022.36.1

Treaties and annuity payments

What is an “annuity,” and how did you learn about it as a kid?

It’s a yearly payment that is part of the treaty. It was negotiated, and it represents a monetary value for sharing the land in the Treaty 3 area. My first experience was getting a government cheque in the mail when I was a kid, then I asked my mother about it, and she said, “You’ll get this for the rest of your life.” And then I found out more about it and that it was all part of that treaty—part of our hunting and fishing rights as well. It’s something that kind of stuck with me.

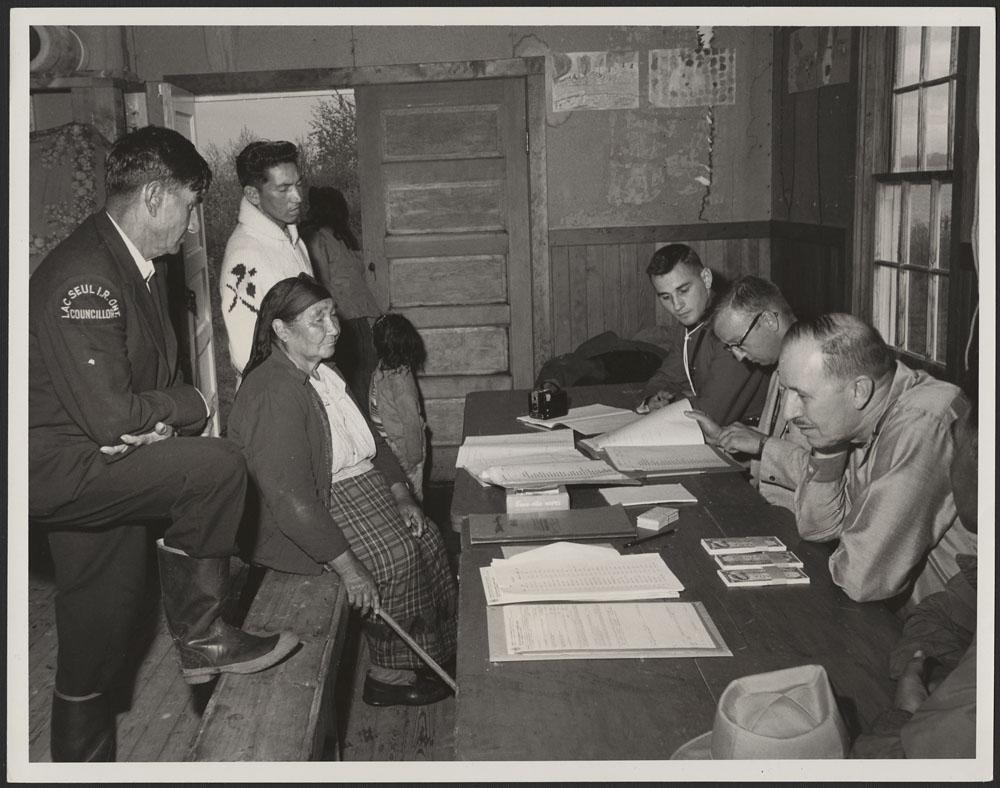

But back in the day, the government would come to the community. They had a ledger book and the money, and you had to show up in person to get it. My wife once volunteered at a treaty payment event when she worked in government. She went to a community outside of Winnipeg, and the treaty event had a carnival aspect to it, to make it fun for the kids.

When you look at the historical treaty document, you can see some contentious parts of the treaty that are still active to this day, but you also see the names of the people that had negotiated and signed the treaty. Treaty 3 took at least four meetings to negotiate with numerous communities and leaders, and some things that were promised orally were not written into the treaty. Today, more than 150 years later, we are still trying to fight for those things. It’s important to celebrate the elders who signed these treaties. They knew the value of what was there and what we should get.

Though most treaty annuity payments are now made remotely, either by direct deposit or mailed cheque, First Nations treaty signatories used to have to travel—great distances, in some cases—to receive their payment in person.

Source: Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Treaty payment, Lac Seul, Ontario, 1900–76; Library and Archives Canada; Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds; e011308331

What do the annuity payments represent to you?

I think some people just see it as money, but it’s more symbolic for me. It’s about an ongoing relationship. It’s important to honour what was said and what was negotiated and not forget about it. I think in the last 10 to 15 years—maybe even 20—we’ve made huge strides in improving the visibility of our culture. We’re here, and we’re not going anywhere. So remembering that history—that’s why it’s important.

More than just money

Why did you use genuine $5 bank notes in the artwork?

I thought it would be great to have all the bank notes from 1972 to 2022 to show the history within my lifetime. I wanted to focus on ideas that I’m familiar with—that I’m living with. And I think it shows how connected Indigenous people are to the government or to the Crown.

We made room for newcomers—we signed these agreements to share the land. Whatever the monetary value of the treaty is, that’s what pays for the reserves, for health care, education. But some people would rather believe that it comes out of their tax dollars. It’s frustrating, you know. Using the actual $5 bills, it just reinforces all of that.

By using real $5 bills from each year of his life in his artwork, Shebageget illustrates his ongoing relationship with the federal government through treaty. It’s a relationship that is often misunderstood by non-Indigenous people, leading to unfair stereotypes.

Source: Detail of Frank Shebageget, Free Ride, framed bank notes, 2022, NCC 2022.36.1

Image : Michelle Beauchamp

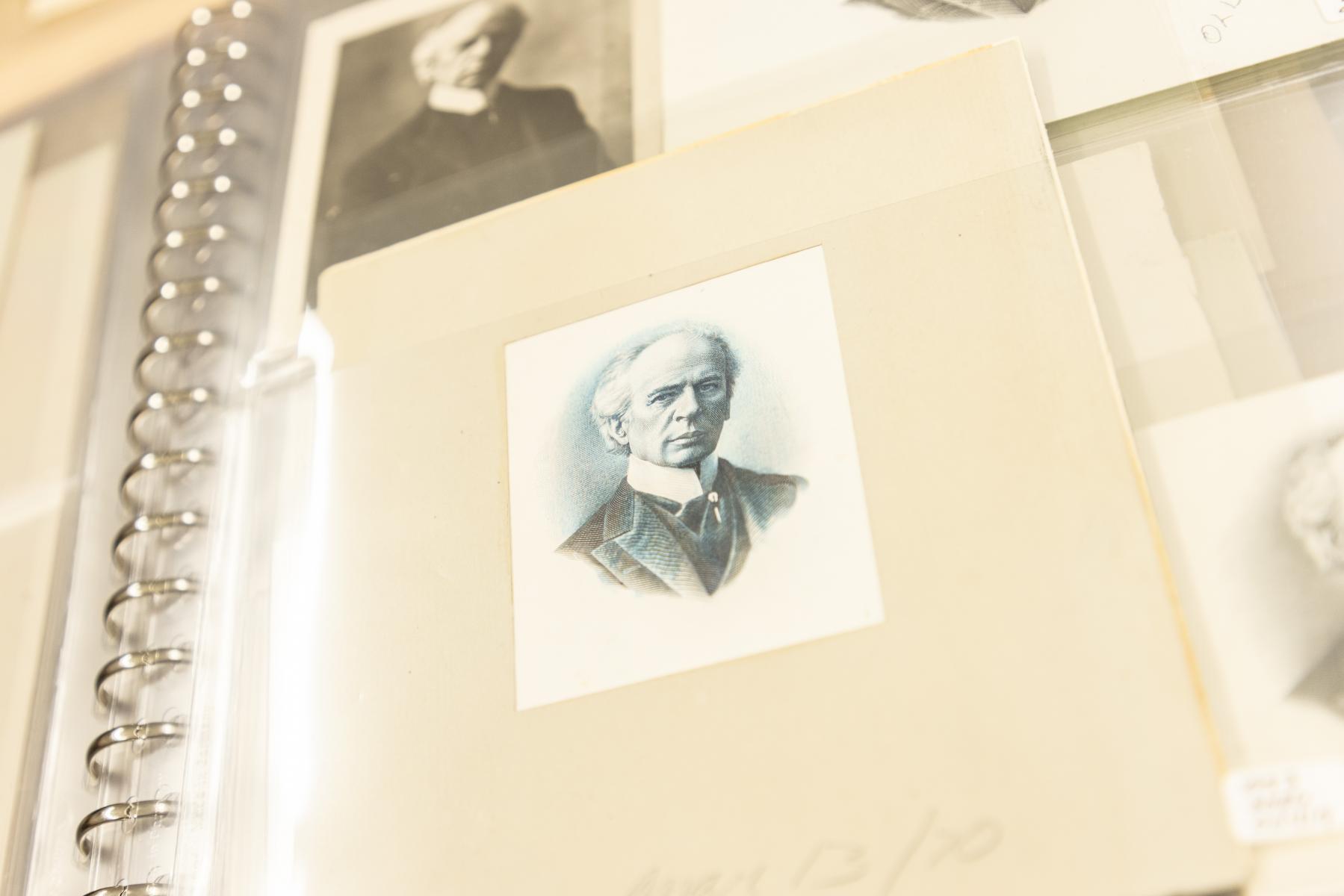

It’s striking to see Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s portrait repeated across the artwork. What does that image mean to you?

He is probably the most iconic Canadian prime minister other than Sir John A. MacDonald. Laurier was prime minister when Treaty 8 was signed. Like Treaty 3, Treaty 8 was about expansion westward. Part of Wilfrid Laurier’s legacy is getting a railway built. He was definitely into nationalism as well: separating more from the Crown and forging relations with the United States. But like most prime ministers, his relationship with Indigenous Peoples was, you know, good and bad. So having any prime minister on the bank note reinforces those connotations with history and prompts the question: what was that relationship like?

I think maybe the next step for me would be to look at some of the older bank notes, especially ones with images of trains, railways and Indigenous people. That kind of imagery would be something interesting to work with.

Shebageget visited the Bank of Canada Museum to examine artifacts related to his artwork, Free Ride, including this printing test of Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s portrait. The portrait appeared on the $5 note from the Scenes of Canada series (issued 1969–79).

Source: Canadian Bank Note Company, die proof, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 1971, NCC 2011.67.796

Image : Michelle Beauchamp

Free Ride and the Bank of Canada Museum

How do you see Free Ride fitting in with the National Currency Collection?

I think the idea of visibility and representation is important for reconciliation. You have bank notes from the time of the treaty, the Hudson’s Bay Company tokens, the trade silver—you can make connections to Indigenous cultures. You know, we are a founding people of this country. But there was a history of erasure here, especially around the time of the treaty and with the residential schools. So just showing that history is important. But personally, I don’t know what reconciliation will look like—that’s the big question everyone has.

This token from the Hudson’s Bay Company was used to help tabulate transactions at its fur trading posts. Trade between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans involved ceremonial protocols, gifts and negotiating the value of natural resources—much like a treaty relationship.

Source: Canada, Eastmain District, Hudson’s Bay Company, 1 made beaver, token, c.1857, NCC 1961.9.2

Settlers often offered silver ornaments as gifts to Indigenous trading partners during the time of the fur trade. Gifts are also an important part of treaty relationships, given as a symbol of the obligations each treaty partner has to the other.

Source: Canada, trade silver, brooch, around 1817–28,

NCC 1966.160.1335

What do you hope the artwork will communicate to viewers?

I hope that it will be a positive learning opportunity. Maybe it will make people want to research the Numbered Treaties. You know, the French–English founding narrative is very ingrained in our nationalism. So inserting the Indigenous view might help people understand that the original intent was to share and prosper together. Everyone just wants to succeed. Even 150 years ago, Indigenous people just wanted to succeed and look after their families.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.