From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

A collection with many purposes

When curators propose new acquisitions for the National Currency Collection, they consider the collection’s many different purposes. It is an important repository for our numismatic heritage, and it tells unique and personal stories about individuals’ experiences with money and the economy. Each object is carefully collected with these different functions in mind.

Preserving our numismatic heritage

A landmark collection of two-dollar coins (toonies)

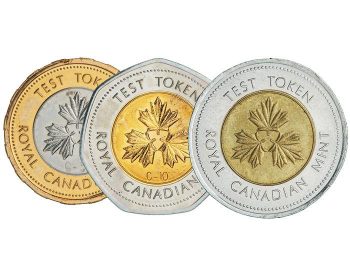

In June, the Bank of Canada Museum acquired a significant part of the Jaime Flamenbaum collection of Canadian $2 coins, widely known as toonies (or the variation, twoonies). While we have collected circulating examples of the $2 coins since their first appearance in 1996, this acquisition adds rare varieties. It also allows the Museum to recognize Mr. Flamenbaum—one of Canada’s foremost expert on collecting $2 coins—and document his contribution to numismatics. The Museum has greatly benefitted from Mr. Flamenbaum’s research and analysis, and it can finally boast of having one of the best collections of Canadian $2 coins in the world!

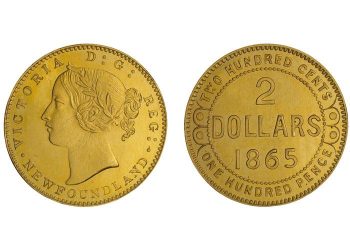

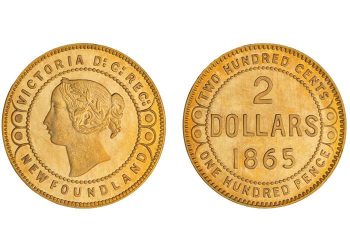

Unique Newfoundland and New Brunswick pattern coins

The Museum acquired several unique and significant coin patterns from two prominent Canadian collectors who passed away in recent years: Harvey Richer and Geoffrey Bell. Dr. Richer was a professor of astrophysics at the University of British Columbia and an avid coin collector. In 2017, he authored the definitive book The Gold Coins of Newfoundland 1865–1888 and was a well-known authority on the subject. The Museum acquired the crown jewel of his collection, a unique $2 gold pattern from 1865. It is one of three different types, of which one was already in the National Currency Collection and the other in the UK-based Royal Mint Museum collection. Harvey passed away in 2023.

The other prolific collector, Geoffrey Bell, was a trailblazer in the Canadian numismatic industry and was active on many fronts in the hobby. A school principal in New Brunswick by profession, Geoff was a member of many coin-collecting clubs, societies and organizations at both local and national levels. A long-time advisor to the Bank of Canada Museum, he served as a Director on the Museum Acquisition Advisory Committee and consulted on collection development for over a decade. Following his death in July 2024, his collection of New Brunswick patterns was sold at auction, of which the Museum acquired the following pieces to complete its collection: the 1 cent from 1862; the 5 and 10 cents from 1870 (having once belonged to King Farouk of Egypt); and the 5 cents with the H mintmark, struck in 1875 at the Heaton Mint in Birmingham, England.

By 1870, New Brunswick was already part of Canadian Confederation. So, there was no need for the province to have its own coins. Likely these were made as presentation pieces by the Royal Mint for the World Exhibition in Sydney, Australia in 1870.

Source: 5 and 10 cents, pattern coins, New Brunswick, Canada, 1870 | 2025.19.2; 2025.19.3

Likely another presentation piece, this coin is from the Heaton Mint (hence the “H” mintmark at the bottom on the reverse). Heaton was a subcontractor for the Royal Mint to strike coins. New Brunswick was already part of Canada by 1875, so the coin was not required for circulation.

Source: 5 cents, pattern coin, New Brunswick, Canada, 1875 | 2025.19.4

Telling personal stories

Métis scrip through an artist’s eyes

Museum collections are important because of the stories they tell. By collecting objects with important personal histories and showing them in the Museum, we can ensure that visitors see themselves reflected in narratives about Canada’s economic and monetary history.

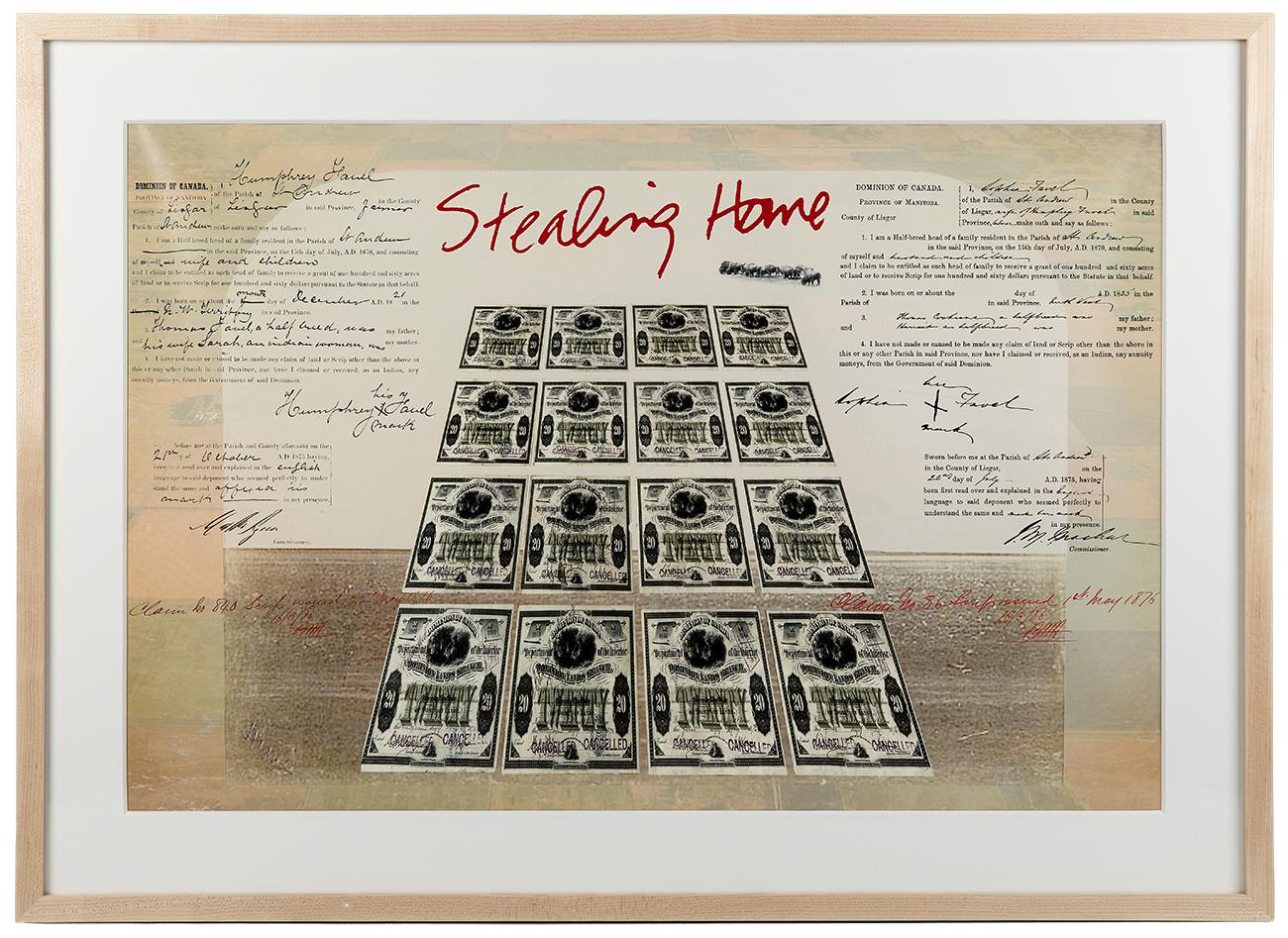

This year, the Museum acquired Stealing Home by Métis artist Rosalie Favell. The artwork tells the story of the Métis scrip system — a system run by the Canadian government from the 1870s to the 1920s. Scrip was the government’s alternative to Treaties for Métis communities in Manitoba and the Prairies: it was a way to extinguish Métis’ Aboriginal title to their traditional homelands, so that the land could be opened for white settlement. The system was badly administered, and many Métis families lost their land. For Métis, the cultural and economic consequences were devastating, while land speculators and commercial banks profited. Rosalie Favell’s artwork tells this important history through the personal lens of her own family’s experience.

Rosalie Favell’s great-grandparents were each entitled to $160 worth of land, issued to them in $20 certificates illustrated at the centre of the artwork. The affidavits her ancestors completed to qualify for scrip are reproduced on either side against a Prairie landscape background.

Source: Stealing Home, ink jet print, Rosalie Favell, Canada, 2021 | 2025.9.1

Records from an immigrant entrepreneur

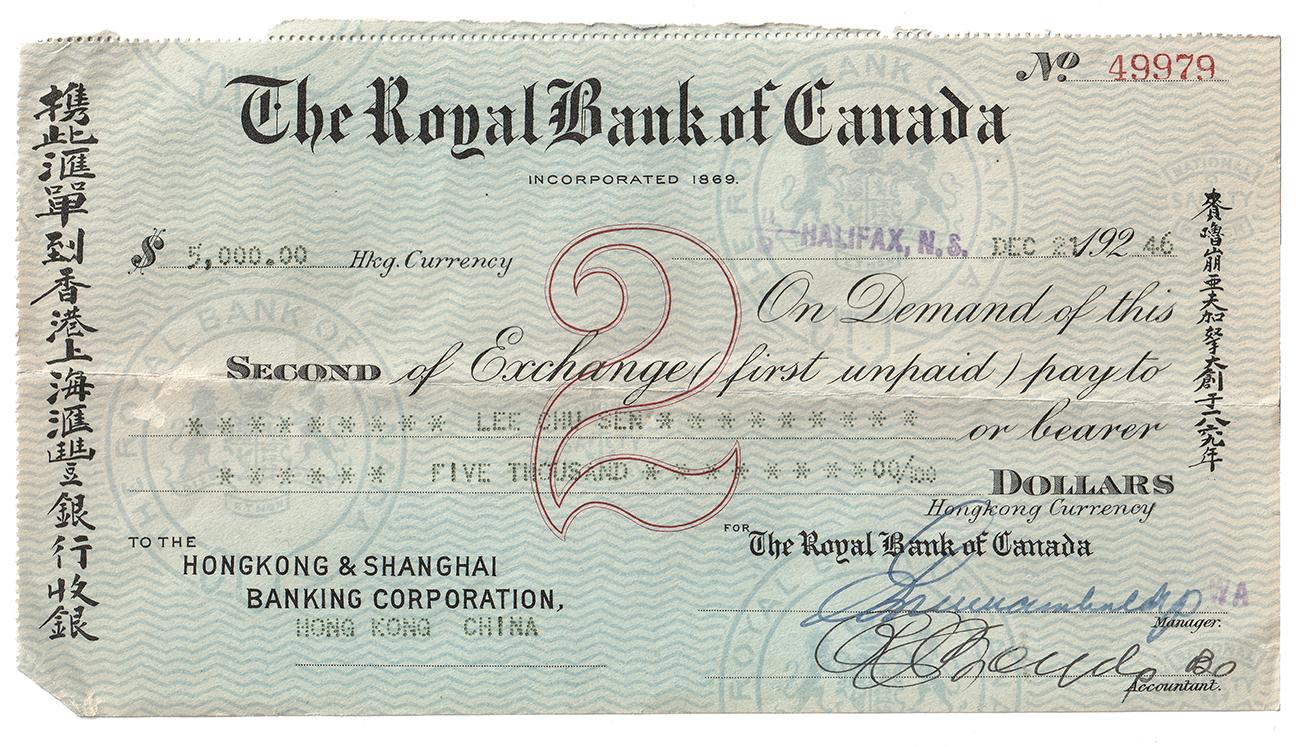

A recent donation shares the story of the Lee family from Halifax, tracing their journey from China to Nova Scotia through financial records and banking ephemera. Donor JJ Lee generously offered records from her grandfather James Tue Lee’s laundry business, which operated from 1927 to the 1950s. For nearly three decades, Lee’s income from the business supported his wife and children in China, who were unable to immigrate to Canada due to the Chinese Immigration Act (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act) of 1923.

The laundry was also a hub for Halifax’s Chinese community, serving as an informal bank for many families. JJ Lee’s important donation tells a compelling story about financial and economic aspects of the immigrant experience in Canada.

James Tue Lee was separated from his wife and children by the Canadian government’s 1923–47 ban on Chinese immigration, so he supported them in China. This bill of exchange from 1946 is made out to his teenaged son, Chew Sen Lee.

Source: $5,000, bill of exchange, Canada, Hong Kong, Royal Bank of Canada, 1946

Image: Justina Yu

Spotlight on new artifacts

As always, there are too many new acquisitions in 2025 to highlight each and every one. But here are more of the notable new additions to the Museum’s collection.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.