Our humble cent carried with it a legacy that spans over a century and a half of Canadian history—from before Confederation into the second decade of the new millennium.

A whole generation of Canadians are coming of age who have (literally) never spent a penny. Since 2012—and the death of our one-cent coin—we’ve all gotten used to rounding off the prices of things we pay cash for. But the cent is still the basic denomination of our currency system and has been since before Confederation.

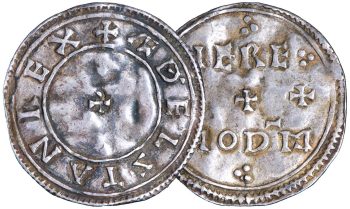

8th Century: The real penny

A pound of silver was minted into 240 pennies. This was the basis of the Carolingian currency system created by 8th century Frankish (French) Emperors. This Anglo-Saxon (English) penny of the same period was based on the same system—one that functioned in the United Kingdom until the 1970s.

Source: 1 penny, Kingdom of England, NCC 925–939 CE | NCC 1965.3.115

Did you know, Canada has never issued a penny?

Canadians (and Americans) have been referring to their one-cent pieces as pennies for as long as these coins have been issued. “Penny” is deeply engrained in our culture and language—much like “loonie” is for our dollar. But cents were never pennies. The true penny was originally an 8th century British silver coin that was a bit smaller (and much thinner) than our nickel. Valued at 1/240th of an English pound, 240 of them were minted from an actual pound of silver. Silver pennies were the basic denomination of the late Anglo-Saxon monetary system and continued in that role in England well into the 16th century—weathering every kind of economic disaster, including invasion and civil war.

The penny may have been England’s lowest denomination, but it wasn’t small change. In the 14th century, you could’ve bought a couple of chickens with just a penny. So, for a large part of the population, the silver penny was simply too valuable for most daily transactions. To make change, it was sometimes necessary, though illegal, to cut a penny in half, into quarters or even into smaller bits. Halfpennies and farthings (1/4 pennies) were introduced by the mint, but in later years this problem was better solved with copper tokens and coins—pieces most of us can better identify as pennies.

18th Century: The coming of copper

The biggest problem with any currency made of valuable metal is the constantly fluctuating market price of the metal itself. This means that a coin’s buying power could also fluctuate. Over the centuries, silver prices rose but generally parallel to the prices of most items—requiring only the occasional adjustment in the penny’s size. However, the 16th century saw significant shifts in the price of silver, making it increasingly difficult to continue issuing the silver penny.

And a great need still remained for smaller denominations, a need that wasn’t being met by the Royal Mint. When it did issue silver half pennies, so small were they that there was a constant risk of losing them. To address these issues, 17th century businesses and other organizations in the United Kingdom began issuing copper tokens that circulated in the economy as both advertising and small change. Popularly known as “coppers,” most of these tokens (many were restamped farthings) were worth half a penny or a quarter of a penny. As silver prices skyrocketed in the mid-18th century, the United Kingdom finally gave up on the silver penny, choosing to issue its first copper version in 1797.

At the same time, it outlawed the use of coppers.

The “Canadian penny”

British soldiers are believed to have brought hundreds of these Wellington copper tokens to Canada during the War of 1812. Tokens similar to this—often called coppers—filled a currency gap in the Canadian economy until replaced by government-issued bank notes and coins.

Source: ½ penny, token, Great Britain / Canada, 1812 | NCC 1964.43.504

1858: Canada’s first cent

Prior to Confederation, the original provinces issued their own copper cents. They were a shade bigger than our modern quarter. Unlike the British penny, Canadian cents were based on a decimal system: 100 cents to the dollar. The Province of Canada (today’s Ontario and Quebec) issued its first one-cent pieces in 1858 and 1859. But the government had overestimated Canadians’ need for copper coins. The Royal Mint in London produced 10,000,000 of them! At the time, plenty of big copper tokens and coins still circulated in the economy, and the “little” government copper coins weren’t so attractive. The new Dominion of Canada didn’t bother issuing another cent until 1876.

1908: A locally-made penny

Until 1908, all of Canada’s coins had been made in the United Kingdom, then shipped to Canada—an expensive and risky operation. So, the Royal Mint opened a branch plant in Ottawa in 1908. In 1931, the facility was transferred to the Canadian government and became the Royal Canadian Mint. But the dies (engraved steel stamps used to make the coins) were still made in England and would be until the 1940s.

1920: The big shrink

Just as they did with the British penny, rising copper prices began to affect the cost of minting the Canadian cent. The First World War had accounted for a large part of the world’s available copper, pushing its price to the highest levels it would see for a century. The big cent was costing far too much to make, so the Mint shrank it from 24.4 mm to 19.05 mm across.

1936: The year of the dot

After the death of King George V in early 1936, King Edward VIII stepped up to the British throne—then stepped back down 11 months later. This left mints all over the British Commonwealth scrambling to produce coins with an effigy of Edward’s replacement, King George VI. To meet immediate public demand, the Royal Canadian Mint was obliged to re-issue some of its 1936 coins: the 1, 10 and 25 cents. A discreet little dot was placed on them to indicate that they were 1936 coins issued in 1937. In the end, the one-cent dot coins were never issued, and the three known examples are valuable indeed.

1937: The maple leaves we all know

In 1936 and 1937, a competition took place to develop a more Canadian look for our coinage. Unhappy with the submissions for the low-value coins, the Royal Canadian Mint turned to the Royal Mint for additional design options. George Kruger Gray, an extremely prolific British coin designer, created a design of two maple leaves for the one-cent piece. Though the maple leaf had always been a secondary part of the cent design, Kruger Gray’s big, realistic leaves were the star feature of the new coin. The maple leaf twig would remain unchanged to the end, becoming a true Canadian icon.

1967: The maple leaves take a break

For 30 years, the only things that changed on the cent were the date and the reigning monarch. But to commemorate Canada’s centennial in 1967, the Mint temporarily changed all its coinage. This commemorative series of six coins was designed by the much-respected Canadian artist, Alex Colville. His strikingly simple designs feature animals that he felt represented the Canadian spirit. For the cent coin, he chose a rock dove. Though it is closely related to the less respected urban pigeon, Colville felt the bird has “…associations with spiritual values and also with peace.”

1977: The little penny that couldn’t

The price of copper was again on the rise, and the Mint was interested in reducing the cost of issuing the penny. So, it proposed shrinking its diameter by 3.5 mm, necessitating a major redesign. The Mint was at the point of striking test coins when it was brought to a halt by a city transit authority. The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) had for decades been issuing tokens designed to fit into the hundreds of turnstiles that stood in its 48 subway stations. The proposed new cent was the same size as the TTC’s tokens. This would have left the commission open to massive fraud or forced it to modify its turnstiles and issue new tokens. The TTC, and a number of other organizations that used similarly sized tokens, protested to the Mint, halting production of the new penny.

1982: The dodecagon

Curiously, after its 1977 proposal to shrink the cent, the Mint made no immediate attempt to reduce its copper content. The copper was mixed with a little more tin, making it technically a bronze coin. But at 98%, it was about as copper a coin as it had ever been. It did change shape, however—subtly. At first glance, it might appear to be a round coin, but the edge of the new penny actually had 12 sides. This change was designed to make cents easier to distinguish from nickels in the pockets of the blind and partially sighted.

1997: Goodbye to copper

When the Mint finally decided to reduce the copper content of its one-cent piece, it did so dramatically. In 1997, the cent went from 98% copper content down to 1.6%. It effectively became a zinc coin electroplated with a whisper-thin coating of copper to retain its traditional appearance. The penny also returned to a smooth round shape.

2000: The steel penny

In a continuing effort to reduce costs, the Mint changed the content of all its coins to steel with a pinch of nickel. The one-cent piece also received a heavier copper coating for extra corrosion resistance. For the first time in its life, the coin’s copper content actually went up. But at 4%, it was still miniscule. This formula would remain unchanged until the Mint shut down the one-cent presses in 2012.

2012: Rest in peace, Canadian penny

Canada stopped issuing pennies for purely economic reasons. At the time of its demise, each cent cost 1.6¢ to make. This would be reason enough to cease production of any currency. But there was also little you could buy with one cent. A mid-19th century cent had the purchasing power of 35¢ when converted to today’s value. By 2012, it was primarily used to make exact change. The United States Mint began phasing out its one-cent piece in 2025. Each one was costing nearly four cents to produce, an estimated US$56 million in costs.

From 1908 to 2012, the Royal Canadian Mint produced 35 billion one-cent pieces. Just before they began to be taken out of circulation, 6 billion of them were estimated to be in the economy (many likely in jars and ashtrays or under couch cushions). In 2013, stores stopped giving them out as change, rounding prices up or down to the nearest five cents. Businesses collected every cent coin they received and delivered them to banks. Bank account deposits surged as people emptied their coin banks, penny jars and dresser organizers. The Mint shipped over 14 million kilograms to be melted down for their valuable metal content. In all, the federal government predicted it would save $11 million a year by not issuing cents.

But culturally, the penny looks to be here for a while yet. In the English language, the word has been synonymous with spending and saving for more than 1,200 years. “Saving your pennies,” “a penny for your thoughts,” “penny pinching” and “worth every penny” are English phrases we still hear almost daily. (The Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms has 16 penny entries.) Misnamed as it was, the penny is nevertheless foundational to our currency system and not as easy to remove from our culture as the coin was from our economy.

That’s our two cents on the matter. (Couldn’t resist that one.)

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.