350 years of the Hudson’s Bay Company

What most of us know as a department store was for centuries a company whose primary purpose was to acquire fur. Over its 350-year lifespan, the Hudson’s Bay Company has had an enormous impact on Canada’s economy and how the nation was settled.

Founding the “Company”

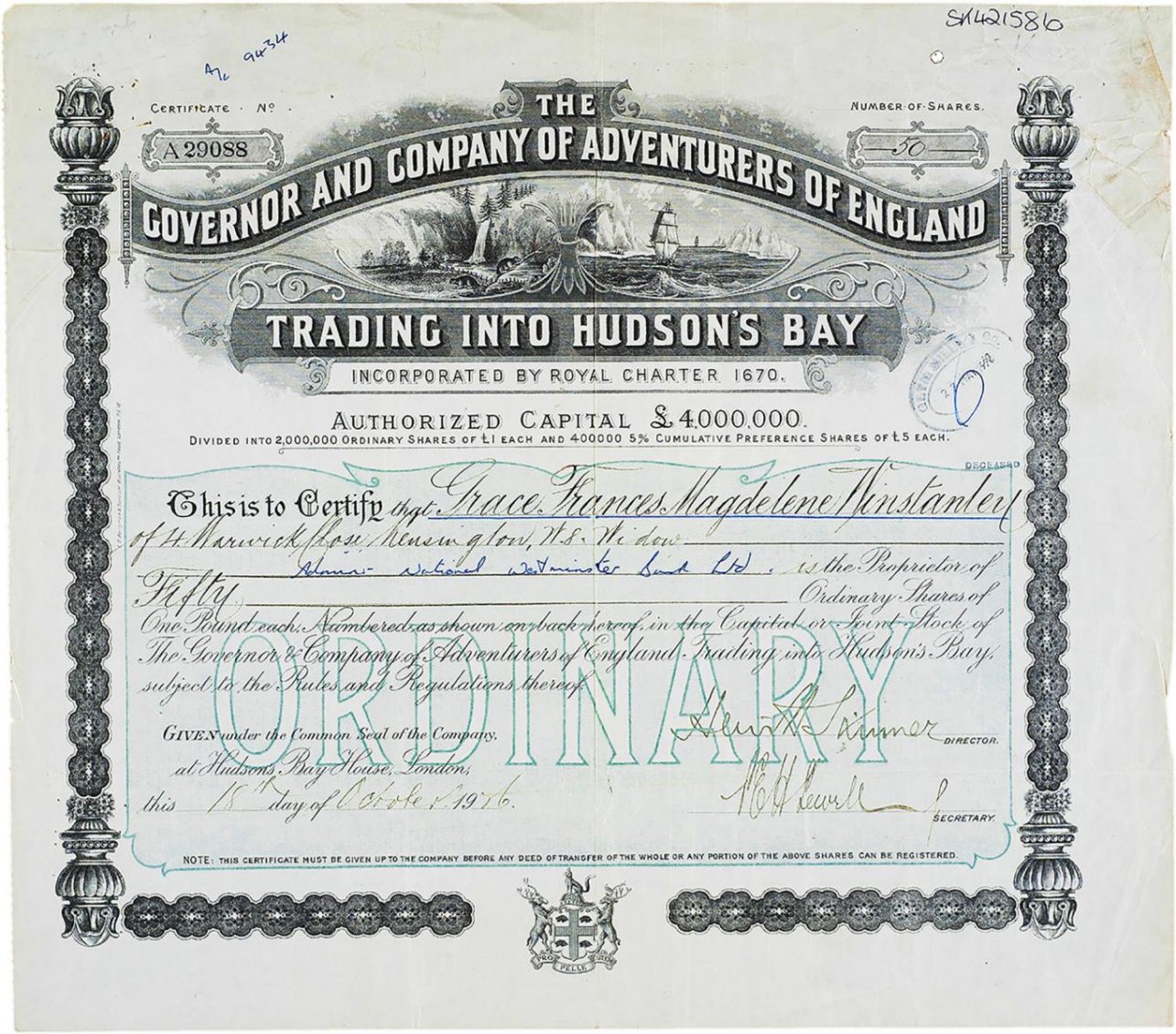

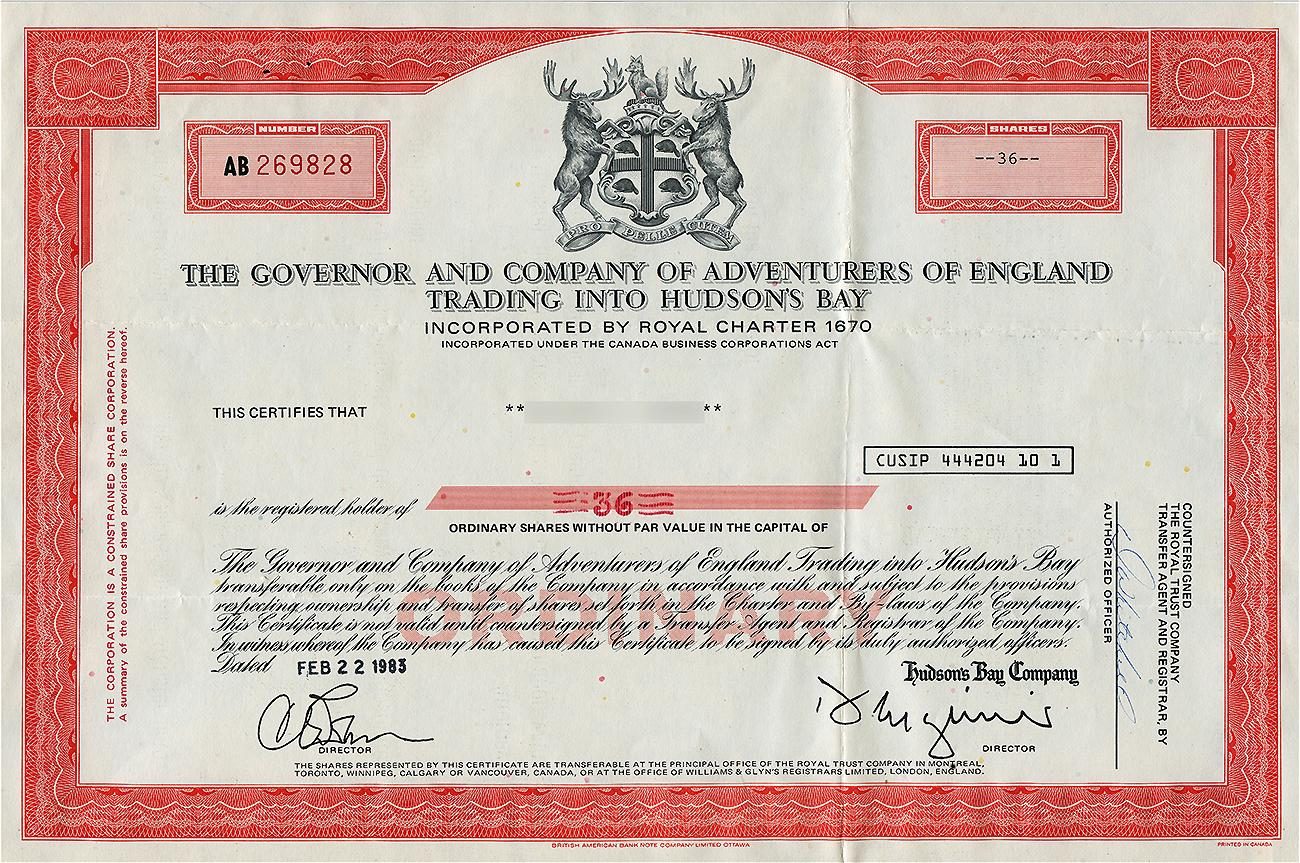

Back in the 17th century, wearing a hat made from beaver felt was expected of every well-dressed man—and Europe had nearly run out of beavers. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was founded mostly to fulfill this need. Established in a London coffee house in 1670, the HBC was initially known as “Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into the Hudson’s Bay.” Its plan was to exploit the enormous supply of beaver swimming around the ponds and creeks of North America’s vast, northern interior for export to European markets.

Though it seems an extremely remote location, Hudson Bay provided traders with immediate water access into the interior. It also allowed traders to avoid conflicts with the French, who controlled the St. Lawrence River.

Although it is evident today that the British Crown had no claim to the land, a royal charter granted exclusive trading rights to the HBC in the Hudson Bay watershed. This vast landscape included the ancestral territories of many Indigenous nations. However, the Crown did not recognize the sovereignty of non-Christians. The region included present-day Manitoba, Saskatchewan and parts of Alberta, Ontario, Quebec and the Northwest Territories. It was renamed Rupert’s Land after Prince Rupert, Charles II’s cousin and the HBC’s main backer. Naming it was effectively claiming it.

Over its history, the HBC—along with the rivals it would absorb—established around 500 trading posts across Canada. Some were mere crossroads in the bush; others became cities and towns we are familiar with today.

Of tally sticks and trade silver

For the first 200 years of the HBC’s existence, the beaver was the basic unit of account in the company’s ledgers. This meant that any item supplied by a trading post was priced in “made beavers.” A “made beaver” was a winter beaver skin in prime condition. These pelts were brought into trading posts by Indigenous hunters who trapped in the fall and winter and travelled to the posts on Hudson Bay in the summer. Starting in the mid-1700s the HBC opened more trading posts in the interior. They hired French Canadian voyageurs to transport furs from the inland posts to the coast by paddling enormous freight canoes along the vast network of rivers that drained into Hudson Bay. Away from the major trade routes, some Indigenous trappers acted as agents for communities without direct access to trading posts.

A simple payment system was set up for trade between the HBC voyageurs and Indigenous hunters. Initially, the fur suppliers were paid with a variety of local items: tally sticks, bone (or stone) discs and shells or beads. They could then exchange these objects for supplies or goods at one of the hundreds of trading posts throughout Rupert’s Land. Later traders used small silver decorative items made from melted coins. Each represented a specific number of made beavers.

As the fur trade expanded, so too did the variety of supplies available for purchase at the posts. Common trade goods included rifles and knives, pots, kettles, tobacco, cloth, glass beads and liquor. The iconic Hudson’s Bay point blankets were used as currency among Northwest Coast First Nations through the potlatch system. Debts were paid in blankets, and other goods were denominated in terms of blankets. In providing the Indigenous people with European products, the HBC also created a need for such items—shifting self-reliant Indigenous economies toward a certain level of dependence upon Europeans.

Paying the suppliers, paying the shippers

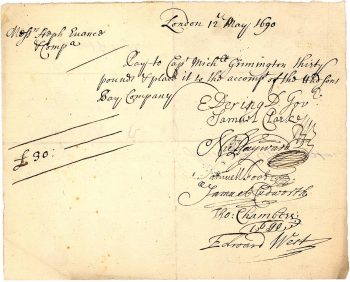

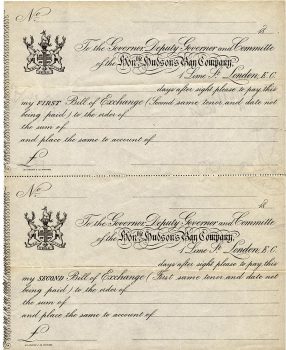

The people who supplied the items stocked in the trading posts were hardly going to accept beaver furs as payment. So, suppliers and shippers were paid in ways more familiar to them. The HBC relied upon “commercial paper:” pay orders, bills of exchange, drawn notes and cheques. Although they were each different payment options, these were all basically like a modern cheque: documents authorizing movement of money from one bank account and another.

Until the 20th century, the European monetary system was based on hard currency in the form of paper notes and specie—money in the form of gold or silver coins. Commercial paper represented that hard currency when required, avoiding the risky transfer of precious metals from one firm to another. With an efficient accounting system, far fewer gold or silver coins actually needed to leave the financier’s vaults.

This pair of bills of exchange was used by the Hudson’s Bay Company to pay its suppliers in London. Bills of exchange were issued in triplicate and sent on different vessels in case a ship was lost. Only one of the bills was paid out and the others were automatically cancelled.

Source: Bills of exchange, Hudson’s Bay Company, Canada, c. 1885, NCC 1973.67.1

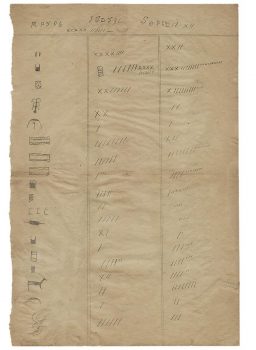

In the bush, the HBC employees also kept meticulous records showing the flow of supplies through the trading posts. A ledger kept by Eshkemanetigon First Nation Chief Sahquakegick, the manager of an HBC post in the Georgian Bay area, shows an itemized list of goods and the numbers of them that had left the post. Pictograms in the left column represent the available blankets, kettles and tools, while columns on the right hold strokes or Xs that indicate how many of each were traded over the summer—a record of the trading post’s inventory.

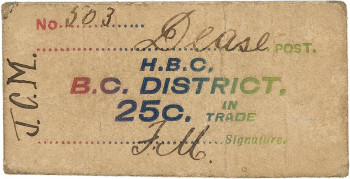

Settlers’ currency: HBC notes and other cash

The HBC’s primary purpose was trade and export of goods. Although the company was not formed with the specific intention of encouraging settlement, this occurred as a natural result of establishing a trade network.

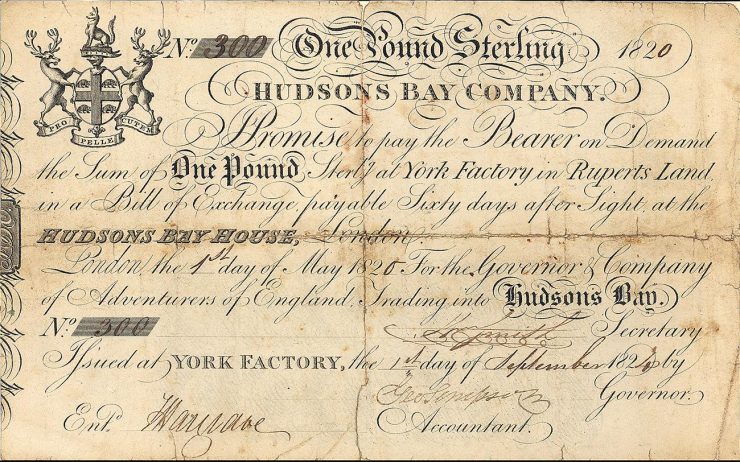

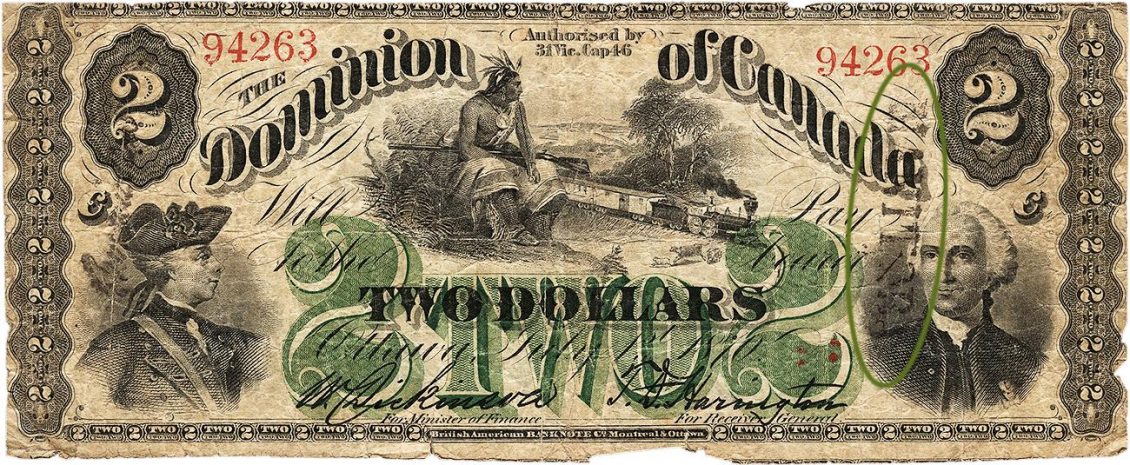

The settlers of Rupert’s Land and the employees of the trading posts needed to be paid in a modern currency that could circulate locally. Andrew Bulger, Governor of the Red River Settlement (Winnipeg), requested a supply of cash from George Simpson, Governor of the HBC’s Northern Department at York Factory (northern Manitoba). In 1820, the HBC shipped £3,000 in promissory notes of 5 shillings and of 1 pound to York Factory. The notes were received in November 1820, but Simpson decided that there was no need for them. Four years later, after receiving direct orders from London, Simpson finally sent the shipment of notes to the Red River Settlement in 1824. HBC promissory notes continued to be put into circulation there until 1870. At that time, Rupert’s Land was sold to the Dominion of Canada government and its paper money replaced HBC notes in Manitoba.

Colonial economies

The 350-year history of the HBC reveals how the monetary system in Canada has evolved alongside the country’s economy. It also illustrates the consequences of British economic expansion into sovereign Indigenous territories. The HBC’s expansion through what was known to settlers as Rupert’s Land paved the way for the eventual acquisition of that territory by the Dominion of Canada.

The fur trade fell throughout the 19th century. With that came an economic decline for an Indigenous population that had lost much of its traditional economy. This pressed communities into signing many treaties that, in the end, assured the expansion of the new nation westward across the Prairies.

Indigenous communities adapted to new economic conditions after the decline of the fur trade. Using their knowledge, skills and expertise, individuals supported their families by acting as guides for tourists and government officials, and by operating trading posts. The tourism industry also created a new market for Indigenous-made souvenir art. Nevertheless, HBC stores continued to be a fixture until the late 1980s in many northern Indigenous communities, where they were often the only store around. This echoes the trade monopoly granted to the company in the 1670 royal charter. The examples of HBC currency in the National Currency Collection are important forms of exchange media that help illustrate the company’s complex history that began with the 17th century fur trade.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.