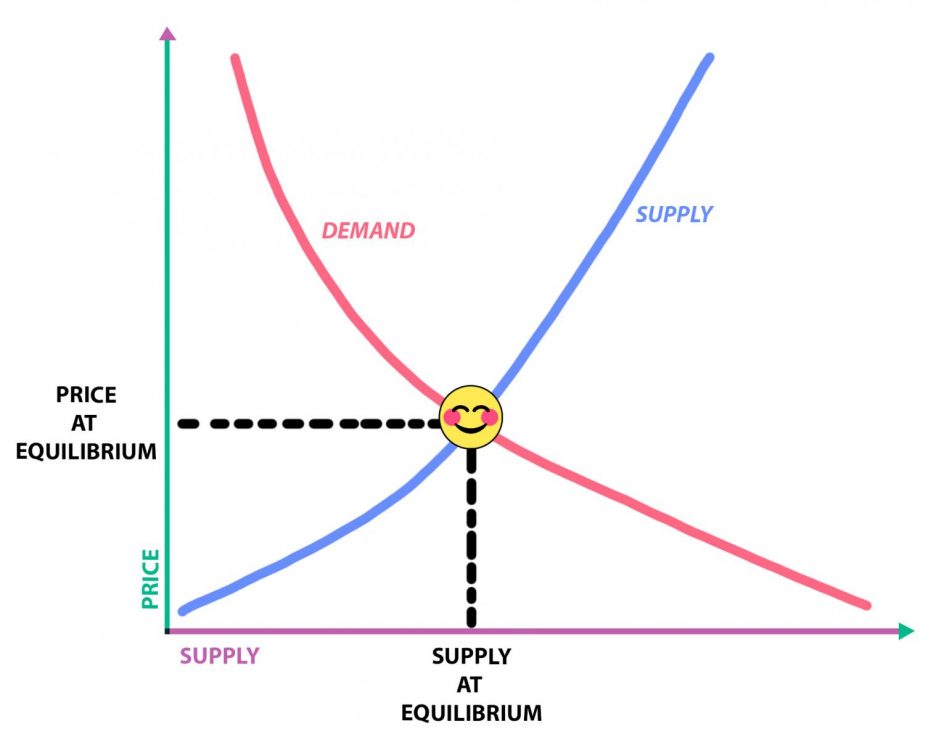

The law of supply and demand

Supply and demand is part of the very bedrock of an economy, generating the price of any product or service.

Alchemy was a medieval pursuit of, among other things, a way to convert cheap metals into gold. It failed miserably—no surprise there. So, what would have happened if an alchemist, let’s call him Elfric, had managed to chemically alter lead and turn it into gold? He’d have become a medieval millionaire, right? Not necessarily.

For one thing, it would be hard to keep such a discovery to yourself, and Elfric is only human. So, he tells his buddy Hammon about it. Later at the inn, after a few flagons of mead, Hammon talks too much about his pal Elfric’s discovery. Soon, every Thomas, Richard and Harold are making gold. People are rolling gold dice and eating off gold plates, and the village council is considering paving the streets with the stuff. Everybody has as much gold as they could possibly want, and its value plummets. “But, ‘tis gold!” Elfric protests. “What the hecketh is going on?”

Elfric just learned a painful lesson about supply and demand—and another about trusting Hammon with a secret.

An economic concept as old as money

European economic thinkers have been studying supply and demand since the 18th century. They recognized a product would only sell at a price that the consumer found fair but that also allowed the producer to make a reasonable profit. British economist David Ricardo stated that the price of an item was directly related to the labour it took to make it. Good solid thinking. But hang on a minute, smart guy. What if nobody wants the product?

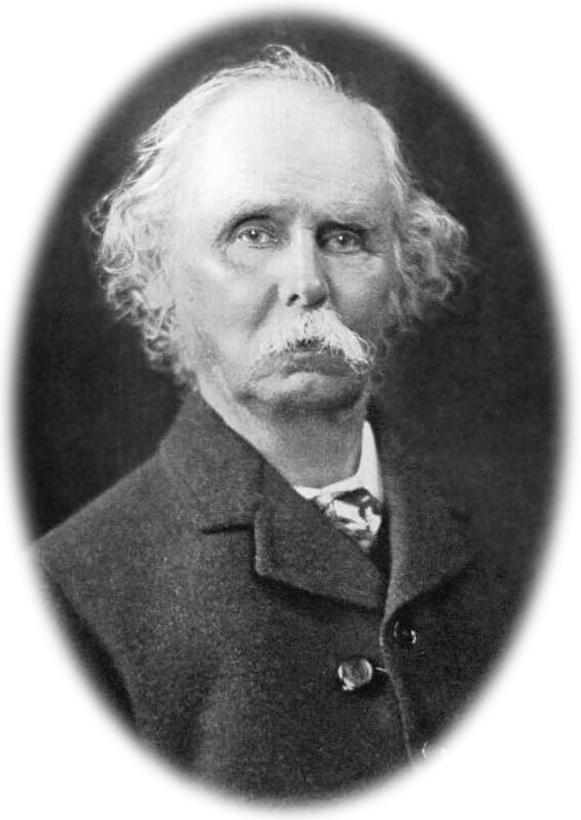

An answer emerged the late 19th-century courtesy of a British professor of political economy, Alfred Marshall. Though he took Ricardo’s point, Marshall’s observations convinced him that the demand for the product was the true generator of its price. Consumers didn’t care how much it cost to make something; the price would only be what they were willing to pay for it. If that price was too low to provide reasonable profit, the product wouldn’t succeed.

At the intersection of supply and demand

Meanwhile, feeling a bit burned after his alchemical failure, Elfric decides to produce something he knows will always sell. Everybody needs shoelaces, so Elfric begins manufacturing them to sell at the village market. But at what price? Elfric is having difficulty meeting the villagers’ shoelace needs and continues to raise his prices to finance his rising production. After a couple of months, Elfric is making a decent living and people seem happy with his prices. Everyone is satisfied.

Demand trumps greed every time

Everyone but Elfric. He reasons that if he could produce more shoelaces, he’d make more money. So, by working nights, he begins pumping out shoelaces left, right and centre. However, with their shoelace needs satisfied, few people are likely to buy any more of them at this time. He has hit the shoelace horizon.

In every case the more of a thing is offered for sale in a market, the lower is the price at which it will find purchasers.”

Alfred Marshall

Elfric is now sitting on a big pile of laces that he spent all his cash to make. And they’re not selling. He has little choice but to lower his prices and have a big sale to cut his losses. The new price nudges people to buy a spare pair of laces, and the demand begins to rise. Soon he will be out of stock, so Elfric begins to raise his prices . . . well, you can imagine where this is going.

Manipulating demand

A store in Slovenia had just received its order of hula hoops in 1959. Who could resist trying one out?

Source: Photographer unknown, Večer (newspaper), Slovenia, 1959

No demand? Create it.

Nobody needed a hula hoop. But Arthur “Spud” Melin, co-founder of the Wham-O Corporation, wasn’t in the business of satisfying needs. The hula hoop was most definitely a “want.” And it sold. In 1958, Melin sent Wham-O representatives to the playgrounds of Southern California, where they gyrated and swung their hips, demonstrating this crazy toy. The kids went nuts. A demand had been created, and roughly 25 million hula hoops were sold in the first four months of production.

Not selling well? Raise the price.

This advice might seem nuts, but some manufacturers of items like luxury cars or watches learned this lesson early on. If your product’s appeal is about showing people how rich you are, then dropping the price to attract more buyers isn’t your smartest move. There’s even a name for this variety of products: “Veblen goods,” named for the economist Thorstein Veblen. A true Veblen good would not offer better quality or performance, just higher status. But it takes the best of economic times to support this type of market.

Want to empty the shelves? Start a craze.

In 1976, Xavier Roberts began selling chubby little handmade dolls in Cleveland, Georgia. A wild success, he couldn’t begin to cope with the demand. In 1982, toy giant Coleco signed a manufacturing deal with Roberts and they called them “Cabbage Patch Kids.” An aggressive marketing campaign followed. As Christmas 1983 approached, the dolls reached a level of popularity resembling mania. At stores in the US and Canada, riots and fist fights broke out among crazed parents. The $17 doll was often purchased by “scalpers” who resold them at $50—$150 each! History repeated itself in 1996 with the “Tickle Me Elmo” doll. Ruthless Elmo profiteers were demanding $500 a copy and giggling all the way to the bank.

It’s all been said before

Taqī ad-Dīn Aḥmad ibn Abd al-Halim ibn Abd al-Salam al-Numayri al-Ḥarrānī was a medieval Islamic scholar, theologian and philosopher. More commonly known as Ibn Taymiyyah, he was a highly influential interpreter of the Qur’an and studied politics, religion, the law, and economics. Centuries before Marshall or Ricardo, Ibn Taymiyyah observed:

If desire for goods increases while its availability decreases, its price rises. On the other hand, if availability of the good increases and the desire for it decreases, the price comes down.”

It’s as simple as that and will never change.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.