A look back at the money of tomorrow

Among the laser pistols, hover cars and androids of science fiction, there’s an elderly elephant in the room: money.

Remember The Jetsons, those campy Flintstones of the future? Their world of 2062 had collapsible flying cars, floating buildings and robot maids, yet they still paid for everything with little green pieces of paper. OK, sure, the creators of The Jetsons were not among the glitterati of futurist prophets, but their vision was far from unique in popular science fiction. There just seemed to be a blind spot when it came to payment methods in the age of the silver suit—it was a place mainstream futurists didn’t like to go.

In space, nobody sees you pay

“Luke! Have you got any cash on you? He won’t take my debit card.” Image: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons

For example, those of us raised on the original Star Wars film will recall a scene where Luke Skywalker’s Uncle Owen buys the robots R2-D2 and C-3PO from the Jawas. He seems to be a hard bargainer, yet only for the briefest of shots do we see Uncle Owen appear to pay the Jawas. Well, he is putting something small into the Jawa’s hands (perhaps the Jawa just dropped its keys), but he’s certainly not looking into a retinal scanner or touching his index finger to a reading device. Still, I can understand how it would be just a little awkward to have your protagonist pull out a wad of $20 bills to buy a robot. It’s not very sci-fi. We presume Uncle Owen didn’t stiff the Jawas, but how did he pay? Payment methods, it would seem, are just not as cool as light sabres.

You see, money doesn’t exist in the 24th century.

Capt. Jean-Luc Picard, Star Trek IV: First Contact

The interplanetary society of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek was often characterized as moneyless. It was a universe where the seemingly infinite availability of all things among dozens of planets would make money obsolete. In the original series, however, in order to obtain a cuddly little tribble (“The Trouble with Tribbles,” Star Trek season 2, episode 15), members of the crew would have needed to pay interstellar trader Cyrano Jones with “credits.” Aha! Not only was it extremely difficult for science fiction to create a suitably high-tech payment method, it is darn near impossible to create a society that functions without a medium of exchange. Money would occasionally pop up in the numerous iterations of Star Trek, for example, the Ferengi’s “gold-pressed latinum” in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine or when Dr. Crusher asks a merchant to charge her for something in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Money, it seems, is simply unavoidable.

In Utopia, you simply can’t pay

And the inescapable necessity of money vexed futurists long before popular science fiction. As in Star Trek, the use of currency was almost taboo in utopian societies.

“Money is the root of all evil.” This 15th-century proverb originates from a biblical quote: “For the love of money is the root of all evil…” (1 Timothy 6:10). There’s a crucial difference here: the later version shifted the blame for some of society’s problems from the act of loving money to money itself. This version appeared to inform the thinking of many utopians of the 18th and 19th centuries who wanted to do away with money altogether. But to be without a medium of exchange was a big roadblock to a functioning society and demanded a lot of imagination of the utopian.

Nineteenth-century social reformer Robert Owen felt that money’s only real value was to represent the occurrence of a transaction. Though his ideal society would have no money, Owen was a practical man who recognized that this was extremely unlikely. Instead, he proposed that money did not need to be physically valuable. In his day, and for part of the 20th century, a paper dollar was supposed to represent a dollar’s worth of gold stored in a vault someplace. Owen’s plan for a future money resembled our own system in that the value of the currency would be guaranteed by the government and not linked to gold.

So, currency, for Owen, could simply be a cardboard token. But for a society to function without currency at all, its very foundations would need to be replaced.

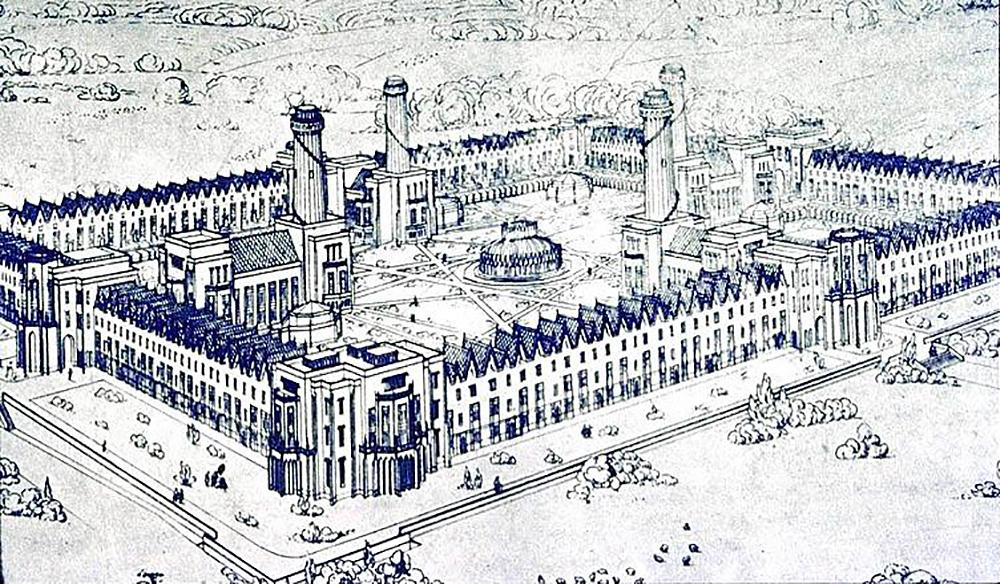

Owen established a utopian commune, New Harmony, in Indiana. He planned to build a grander community, as seen here. But New Harmony’s 1827 economic collapse destroyed his dream.

Image: Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Bellamy was an American whose book Looking Backward inspired legions of followers wishing to change the social order from capitalism to state-owned production. Image: Library of Congress online collection, Wikimedia Commons

And replacing the foundations of society is just what Edward Bellamy, another 19th-century utopian, proposed doing. He dreamt of an America in the year 2000: a state that would own all production and capital and distribute the wealth to the public. Instead of money, Bellamy imagined something he called a “credit card” upon which each citizen was allotted an annual share of the nation’s output. The cards were redeemable for items in standardized shops. It was a system that stripped money down to its most basic function: merely negative and positive entries in a ledger. This sounds an awful lot like the basics of a cryptocurrency. But Bellamy had no technology with which to further his vision of the next millennium. He couldn’t possibly have imagined the internet.

The internet’s the thing

Bellamy wasn’t alone; nobody would imagine such a thing as the World Wide Web for another 60 years. And prior to envisioning the internet, we couldn’t even dream of money’s future. Once the possibilities of computer networking were understood, however, a new future for money leapt into visionary imaginations—at least economically inclined imaginations. In 1965, Thomas J. Watson Jr., chief executive officer of IBM, outlined a futuristic transaction:

To draw down or add to his balance, the customer in a store, office or filling station will do two things: insert an identification into the terminal located there; punch out the transaction figures on the terminal’s keyboard. Instantaneously, the amount he punches out will move out of his account and enter another.

Though Watson got the debit transaction spot on, he could only glimpse the vast possibilities of a worldwide computer network.

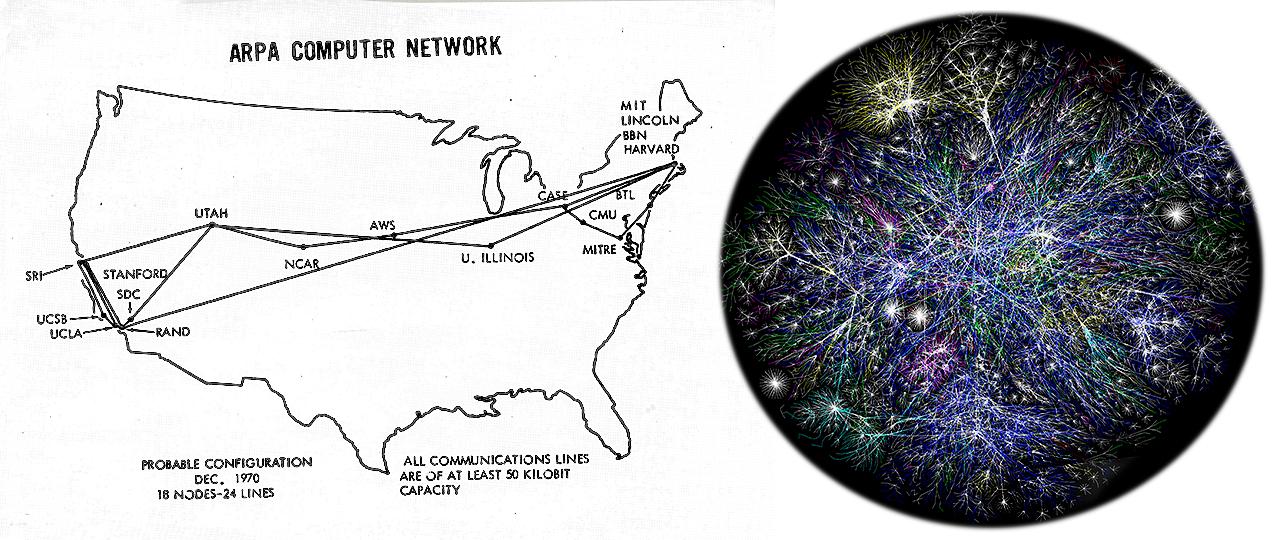

Four years later, reality would begin to catch up. On October 29, 1969, the true mother of the internet was born: ARPANET, or the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network. Direct communications between individual computers were already relatively common. But the developers of this new network invented a process that enabled information to be delivered as small packages in the gaps between messages on telephone networks. It was only four computers, but ARPANET demonstrated a realistic potential for moving and storing vast amounts of information. Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor, and internet visionary, J. C. R. Licklider noted at the time:

It's just fundamental that if one wants to deal with information, he ought to deal with the information and not with the paper it's written on.

And that paper would soon include money. With the pre-dawn of the internet came inklings of a completely cashless, chequeless, tokenless economy—one that didn’t demand the dismantling of modern society. It was a vision of today’s interconnected banking system and e-money. Too bad this never made it to the movies.

On the left is the entire ARPANET of 1971 while on the right is a representation of a mere 30% of the internet in 2005.

Images: UCLA Library/opte.org, Wikimedia Commons

And what does the Bank say?

The Bank of Canada is not in the science fiction business. But it is putting considerable effort into researching the real future of money. And this means keeping a sharp eye on all aspects of “fintech,” or financial technologies. Payment options are multiplying like tribbles, but many of them are just variations on a theme. Some stand out, like cryptoassets. Take a look at this article, which lays out the Bank’s position on, and concerns about, future payment methods in clear and sensible terms. No silver suits, no hover cars.

The Museum Blog

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

An item is said to have cultural value when it can be directly associated with the history, people, beliefs or rituals important to a society. It’s the same with a rai—its value can be greater depending upon who authorized it, who carved it and who subsequently owned it.

Decoding Canadian economic data

Develop data literacy skills by interpreting charts of Canadian economic data.Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon

What the stock market crash of 1929 did was starkly reveal the weaknesses of economic systems that had evolved from the unregulated capitalism of the late 19th century.

Welcoming Newfoundland to Canada

By: David Bergeron

Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation marked the end of an era when Canadian provinces issued their own coins and paper money.

Connecting Canadian industries

Explore different industries in the Canadian economy and see how they are interconnected and evolving.March Break at the Museum

Share part of your March Break with us at the Museum. Drop in for free family activities about counterfeiting and how our bank notes are designed to prevent it or check out our online activities.New Acquisitions—2023 Edition

It’s that time of the year again—the wrap-up of the Bank of Canada Museum’s annual acquisition program. Here are a few highlights of the latest additions to the National Currency Collection.

Winterlude Weekends 2024

Pop in, warm up, and enjoy fun, indoor family activities every Winterlude weekend.Mo’ money, mo’ questions

But what do you do with money once you have it? That’s for you to decide. A budget can really help. It will allow you to keep track of what you earn (income) and what you spend (expenses).

Understanding cryptocurrencies

By: Graham Iddon

Most of us are aware of them, but how much do we really understand about cryptocurrencies?