Money. What do kids want to know about it? What do they need to know?

We invited kids to tell us what they wanted to know about money. A whole lot, as it turned out. More than 800 thoughtful, complex or just plain fun questions flooded in from across the country. And we answered each and every one.

We chose a handful of questions that we felt best revealed what kids really ought to understand about money. Then we answered them with an exhibition: ten play-based activity stations that provide a foundation of what kids need to know to help them manage their financial futures. It’s a space for parents and children to play and learn—very economically.

Exhibition highlights

What did money look like back in the olden days?

Money has been all sorts of things: tea, shells, even beans. We call this commodity money because it’s made of something that is useful. But before it could be used to pay for things, everybody had to agree on what it was worth. “How many beans for that tomato?”

Instructions: Nearly all of these things were used as money. Can you spot the impostor? Click on an image to reveal how it was used as money—or not!

The fanciest men’s hats in Europe used to be made of beaver fur from Canada. Furs were so valuable that traders used them as money.↺

The Aztecs of Mexico believed cocoa was a gift from the gods. Aztecs made it into a drink and used cocoa beans as money.↺

IMPOSTOR! No, coffee was never used as money. But tea was. Made into solid bricks, it bought everything from rice to horses.↺

Centuries ago, most people in China worked on farms. So, their coins were often shaped like the tools that were so valuable to them.↺

The older parmesan cheese gets, the more it is worth. In Italy, there’s a bank that will loan you money in exchange for it.↺

Soldiers in New France were paid with French coins. But sometimes they were paid with playing cards when the coins ran out!↺

Salt is great for preserving food and cleaning wounds. It used to be hard to find, which made it valuable.↺

Seashells were a great form of money. They are easy to carry and hard to copy. Also, their value increased the farther you got from the sea.↺

Money changes, just like people

People’s needs change. And money has changed right along with them—from cows to coins to computer code. Nowadays, almost all money is digital, and technology is giving us new ways to pay. So, how do you think you’ll pay for stuff in the future?

Can money be dinosaur bones?

Dinosaur bones could be money—if all of us agreed that they were. Most things that work best as money are alike in 5 ways. They are long-lasting, easy to carry, uncommon, hard to counterfeit, and they can be divided—like a dollar into quarters. So, does dinosaur bone money make sense to you?

Instructions: Answer the questions below to see if these things could be used as money instead of coins or bank notes. Anything can be money if we all agree to use it that way.

Could this object be money? Is it:

- Long-lasting?

- Easy to carry?

- Uncommon?

- Hard to counterfeit?

- Easy to divide?

Who thought of putting influencers on our money?

The people on our currency might not be on social media, but they were all influencers in their time. Originally, only the Bank of Canada and the government chose who appeared on bank notes—usually past prime ministers and members of the Royal Family. Today, the government still makes the final choice, but for the vertical $10 bill, the Bank asked Canadians whom they wanted to see. In this case, human rights activist Viola Desmond.

Symbols of a nation

You see all sorts of things on a bank note besides an important person. They are symbols, carefully chosen images that represent us and our country.

Why do we have to work for money?

Sorry to break it to you, but without work, money wouldn’t exist. Money represents the time and effort we put into our jobs. So, when you buy a new bike, you are paying for the time and effort it took for people to design, make and sell that bike.

How can kids earn money?

Meet Mya Beaudry, a young entrepreneur, and check out her story about creating her own business.

Some ideas for how you can make money

There are lots of ways for a kid to make money—they just have to look around their neighbourhood and see what’s needed.

- Selling used toys online.

- Dog walking or pet sitting.

- Doing chores for neighbours.

- Helping with yard work.

- Hosting a neighbourhood car wash.

- Putting on a performance and selling tickets.

- Taking photos at local events.

- Collecting and returning cans and bottles.

- Selling their artwork.

- Growing vegetables and selling them.

- Giving music lessons.

Questions about the Collection

Many kids asked us questions about the artifacts in the Museum’s collection.

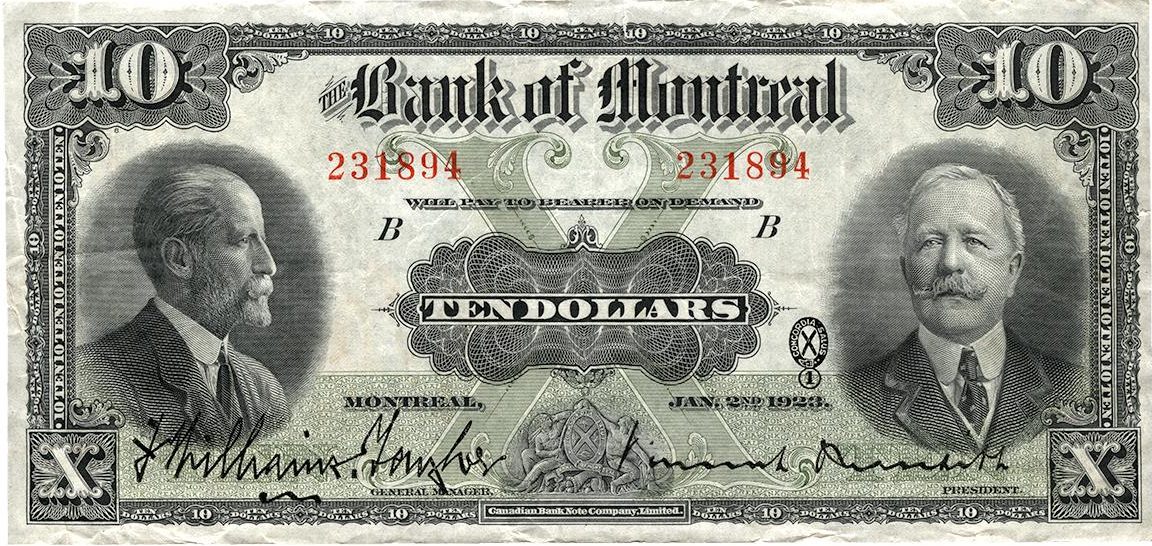

Did money look the same in all parts of Canada?

A hundred years ago, Canadian paper money was a mishmash of notes printed by dozens of banks and the government. It was very confusing. The Bank of Canada took over producing bank notes in 1935. After that, money became the same everywhere in Canada.

$10 bill from the Bank of Montreal released in 1923 | 1961.2.2

Why don’t we make pennies anymore?

Canadians just weren’t using pennies much by 2011. But the bigger problem was that each 1-cent penny was costing 1.6 cents to make. That didn’t make much sense. This Canadian penny is the last one ever made!

Last Canadian 1-cent coin, made in 2012 | 2012.42.1

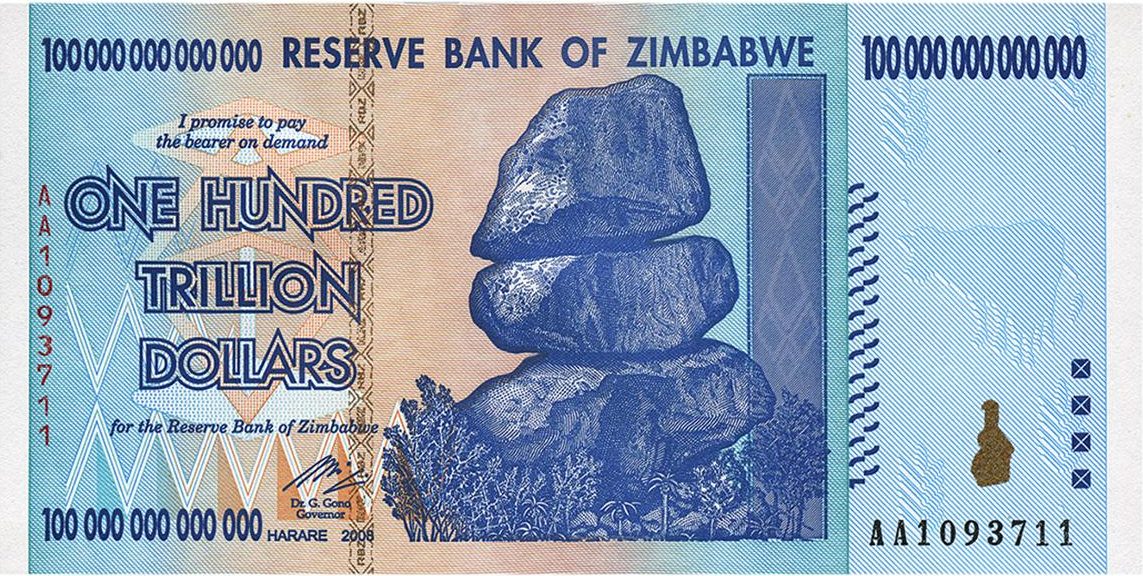

What was the largest amount of money in one bill?

The number on this bill (its denomination) is 100 trillion Zimbabwe dollars! But that doesn’t mean you could buy much with it. This bill is one of the highest denominations ever produced, but it was worth less than 1 Canadian cent! Much less.

Bill for one hundred trillion dollars from Zimbabwe, released in 2008 | 2019.60.6

Online activities

There is a need and an appetite for financial and economic literacy among young people. The Museum has activities to help you keep the conversation going:

- Learn Your Role in the Canadian Economy by playing this game.

- Our Growing Your Savings activity makes saving money fun.

- Making Sense of Currency is an activity that does just what it says.

- Help your kids prioritize their savings with Needs or Wants—that is the Question.

- With our Printable Play Money, your kids can practice counting money and making change.

- Put learning into grocery shopping with our Economics of Suppertime activity.

- Make budgeting fun while making puppets with Avatar Market.

Money in 10 Questions: Kids Edition is a recipient of the 2023 Award of Excellence from Interpretation Canada.