The Bank’s first bilingual notes

During the first century of Canadian banking, a bilingual bank note was an unusual thing. An entirely French bank note doubly so.

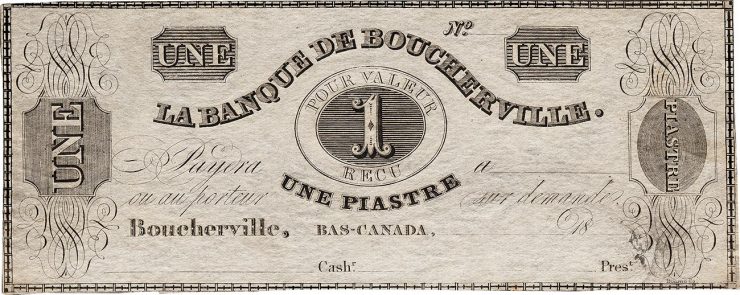

Even French notes usually carried some English banking terminology—in this case, the abbreviations “Cashr.” (cashier) and “Prest.” (president). This rare French note served a very small region. 1 piastre (1 dollar), Banque de Boucherville, Lower Canada, 1835

Just to remind you

Canada’s Official Languages Act came into force on September 7, 1969—50 years ago. The purpose of the Act was to

“ensure respect for English and French as the official languages of Canada . . . in communicating with or providing services to the public and in carrying out the work of federal institutions”

(Official Languages Act)

At its heart, the act was simple and rational. The spirit of it had long been unofficially adopted by many institutions for public services, official documents, road signs and, yes, bank notes.

The elusive bilingual bank note

The first Canadian bank notes were issued in 1817, and for the next 120 years, the vast majority of Canadian notes came in only one flavour, English. So much of the early banking industry was run by anglophones that even in Lower Canada (Quebec) a French or bilingual bank note was rare currency. Certainly, the jargon and traditional terminology on a note were usually in English no matter where the note came from.

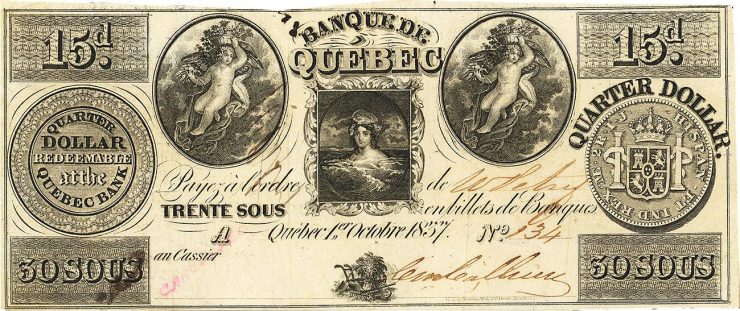

This note from Québec is mostly French and a little bit English. The denomination is expressed in British, French and American currencies—an interesting reflection of the Canadian economy of the day.

30 sous / 15½ pence / ¼ dollar, Banque de Québec, Lower Canada, 1837

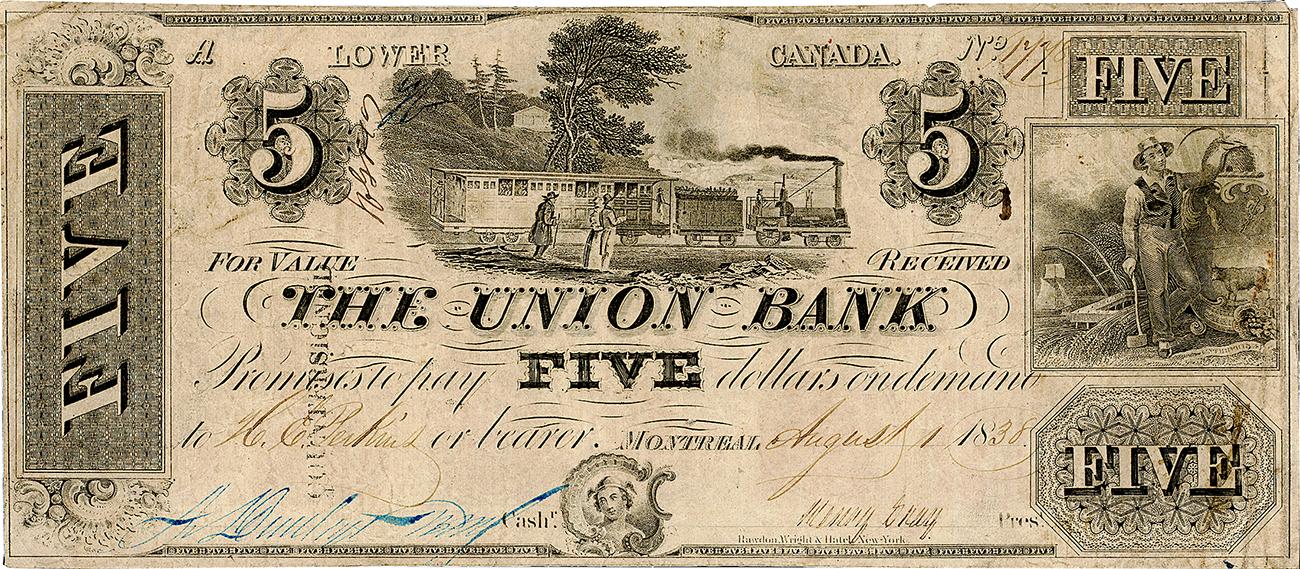

This is more typical of a note from Quebec. It’s from a Montréal bank and entirely in English. At this time, Canada had yet to officially adopt the dollar as its base currency, and notes were just as likely to be in pounds as in pence or piastres.

5 dollars, The Union Bank, Lower Canada, 1838

An uncomfortable partnership

The Canadian economy of the 1800s was made up of dozens of chartered banks, mostly serving very narrow territories. They printed their notes in whatever language (and currency) was most appropriate for their clientele. The notes were overwhelmingly in English. In 1840, the “Act of Union” was passed, and Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) became the Province of Canada. In 1866, the province began issuing its own currency for public circulation. Much to the frustration of the French half of the new province, all the notes were printed in English—and would remain so for nearly 70 years after Confederation.

“Jacques Cartier” is the only French aspect of this note. Although a federal note, it was redeemable for gold only in the city of its issue: Montréal. 1 dollar, Dominion of Canada, 1870

1935: A dollar for each solitude

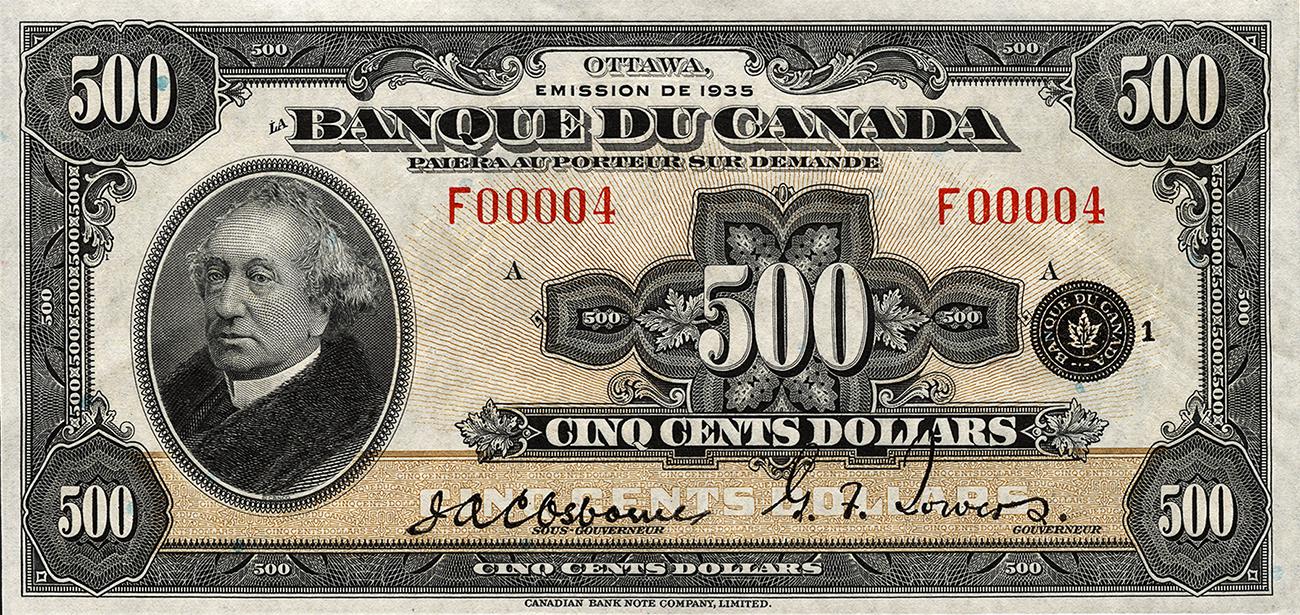

The Bank of Canada’s first note series was developed by the federal government, not the Bank. Production was timed so the notes could be issued on the day the Bank opened for business: March 11, 1935. The Bank and the government of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett were well ahead of Official Languages Act requirements by issuing bank notes in both English and French. But, curiously, they chose to issue two separate sets of notes, one in each language.

Of the roughly 120 million bank notes printed of the 1935 series, around 20 percent were in French.

1 dollar/1 dollar, Canada, 1935

Only 5,000 French $500 bills were issued in 1935. A mere handful are known to still exist, and 6 of the original 5,000 remain unaccounted for. Price guides won’t even hazard a guess as to the market value of these rare notes.

500 dollars, Canada, 1935

As you would expect, most French notes were issued through the Bank’s Montréal agency. But, according to the Charlton Standard Catalogue, a small percentage of them were distributed nationally to serve the broader francophone population. You might already have spotted the problem here.

Currency, by nature, circulates like water. And it wasn’t long before bank notes issued to meet the expectations of French Canadians turned up in the wallets and purses of English Canadians (and vice versa). The then Bank of Canada Deputy Governor John Osborne noted in a letter to British colleagues that

“the English-speaking population is inclined to mutilate the French notes, and the French population complains they cannot get enough of their own notes.” *

A most Canadian of problems. But an obvious compromise was on its way in the form of an amendment to the Bank of Canada Act. The mere thirteen words would change our bank notes forever.

1937: A dollar for both solitudes

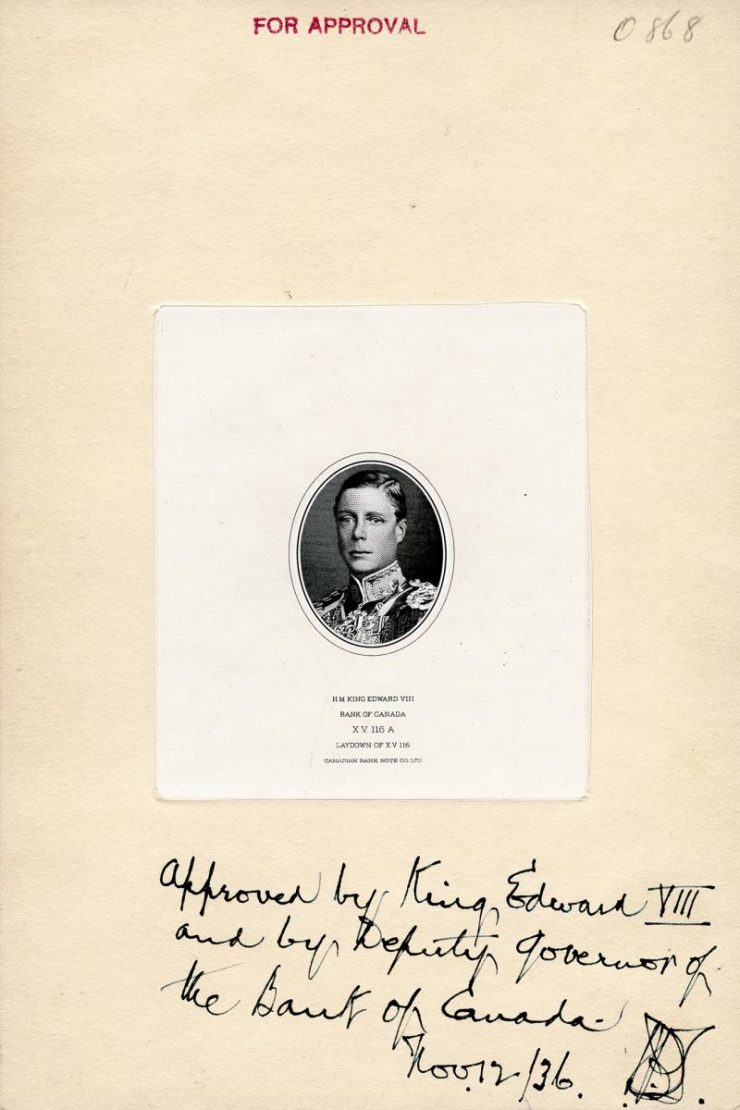

This portrait would have appeared on the 1937 bank note series. “Approved by King Edward VIII and by Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada. Nov 12/36.” Edward abdicated a month later. Die proof, Canada, 1936

The form and material of the notes of the Bank shall be subject to approval by the Minister, but each note shall be printed in both the English and French languages.

Bank of Canada Act (Section 25)

Those thirteen words lay at the root of much debate in Parliament; but in the end, the plan was widely regarded as a good decision. The opportunity to put the plan into action occurred in January 1936, when King George V died. The Bank needed to prepare a portrait of the new sovereign, Edward VIII, for upcoming bank notes, and used the opportunity to revamp the notes’ overall design. This decision included making all the notes bilingual. (Fortunately, the new notes were still in a prototype stage when Edward abdicated later that same year.)

The abdication of King Edward VIII forced the Bank to reuse the 1935 portrait of George VI to get the series out on time. He appeared on all but the $100 bills and $1,000 bills. 20 dollars, Canada, 1937

A (mostly) new note

“Repairs the blunder,” stated Québec City’s La Nation.

“Bilingualism run rampant,” declared the Toronto Telegram.

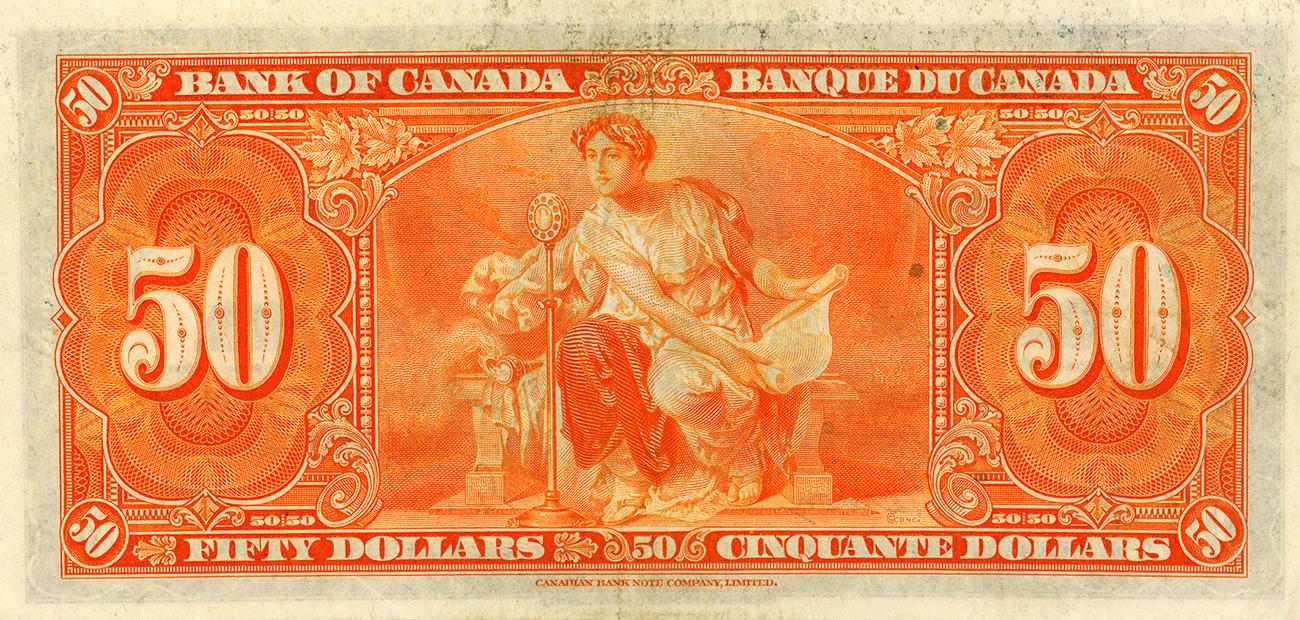

Though the bilingual content put the 1937 notes decades ahead of official government communications and services, they still closely resembled the 1935 series. Best described as Victorian in design, they featured most of the same allegories for the back vignettes.However, there were major differences between the series. To facilitate dividing the note design into French and English, the designers moved the portraits to the middle. (This also kept the King’s face away from the inky fingers of bank clerks as they counted the notes.) They made the arrangement of the back vignettes far more uniform and also altered or reassigned the colours. With the exception of the bright orange of the $50 bill, the familiar colour patterns we still see on our notes were firmly established in this series. But the new colours created a bit of a problem.

The orange ink of the 1935, 1937 and 1954 $50 bill contained toxic metals and was later discontinued. The red we now associate with the $50 bill was introduced in 1975. 50 dollars, Canada, 1937

The 1935 and the 1937 series were very similar in style. But one major difference was the seal of the Bank of Canada, which appeared on the right half of the 1935 note faces. This was the only series to feature it.

5 dollars, Canada, 1935/1937

When the 1937 series was ready to be issued, a considerable stockpile of the 1935 series remained in the vaults. The Bank planned to continue releasing the rest of the 1935 notes as usual and hold back the 1937 notes until needed or requested.

But the colour changes to the new series brought some confusion: the 1935 $2 bill was easily mistaken for the 1937 $5 bill. Three dollars was a fair bit of cash during the Depression, and few could afford that sort of mix-up. So the Bank destroyed remaining stocks of the older $2 note and took existing ones out of circulation.

By 1938, the Bank was phasing out most of the 1935 notes, well ahead of its intended schedule. The 1937 $1,000 notes sat in storage until they finally superseded the 1935 versions in January, 1952—a mere two years before they were in turn replaced by the new 1954 $1,000 bill.

By then the standard of bilingual bank notes was firmly set as part of the country’s cultural tradition. Each subsequent bank note—including the most recent $10 note featuring Viola Desmond—has made its own contribution to the richness of Canada’s ongoing story in both official languages.

For further reading and information

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

By: Graham Iddon

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon