Paul’s odd Saturday morning

This is the first of a two-part blog concerning our Chief Curator’s shopping trip to a Montréal auction house. It is one of his tasks to help grow the National Currency Collection of the Bank of Canada Museum.

It’s 5:10 Saturday morning. Some song on the radio rips me out of a pleasant sleep. I quickly whack the snooze button so as not to disturb my wife and then slump down again into my pillow only to be startled five minutes later by Justin Bieber…I think.

Saturday, 14 May 2016 and it was not the usual start to my weekend. Instead of rising early, reading for a couple of hours and then enjoying a leisurely breakfast, I was up, showered, shaved, dressed, in a cab and then on a bus heading for Montréal.

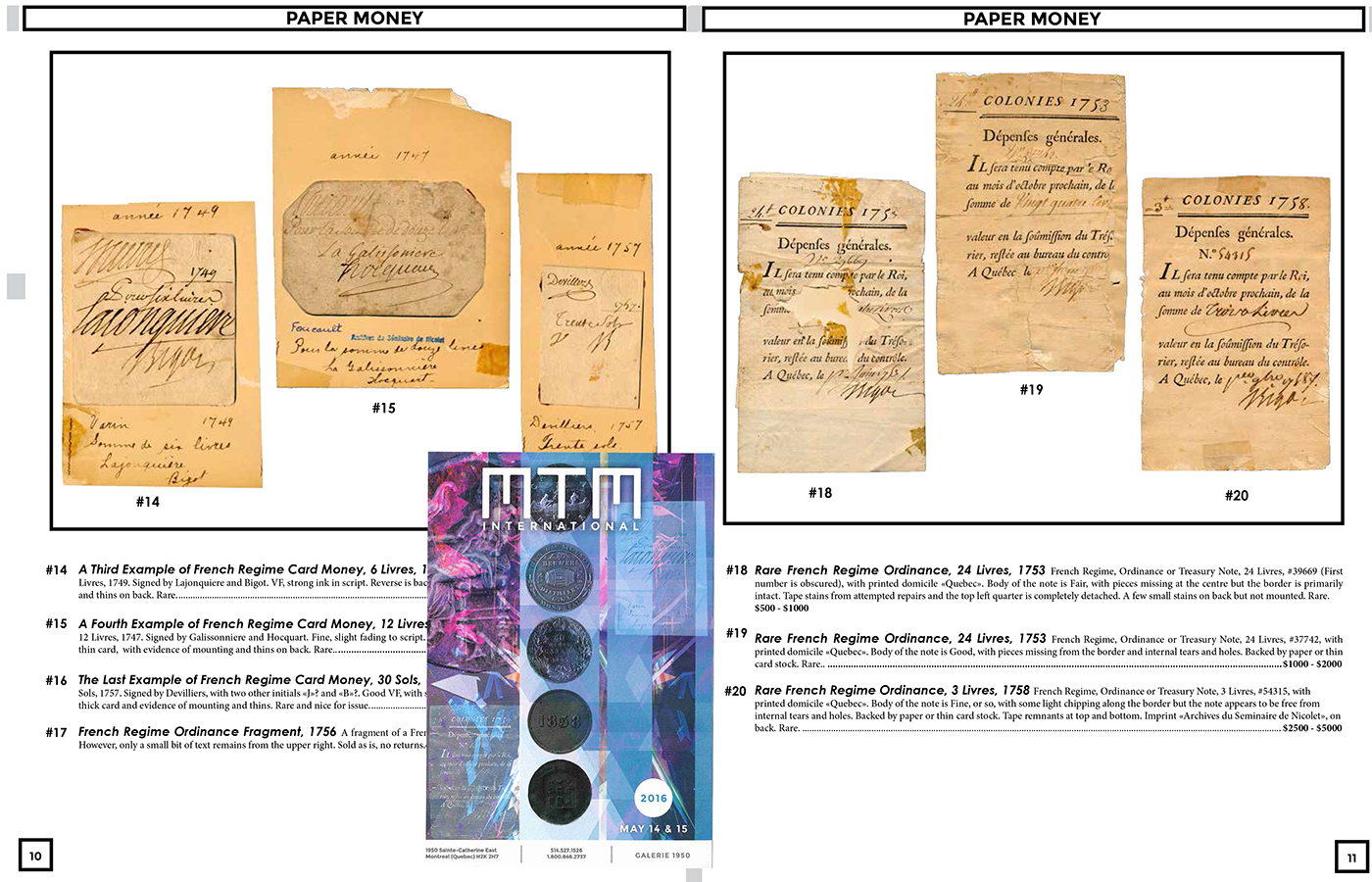

Why was I doing this? MTM International, a collectibles store on Sainte-Catherine Street East, was holding a two‑day auction featuring numismatic rarities from the seminary of Nicolet. (former Catholic college near Trois-Rivières, Quebec, opened early 1800s) The sale included the largest assemblage of French Regime paper money auctioned in Canada, including several items that were not in the National Currency Collection. In previous weeks, following notice of the sale, I had viewed the offerings online, identified pieces of interest and determined what we could afford.

Montréal from Mount Royal. Attending the auction personally is the best route to auction success.

I could have participated from Ottawa, by sending in advance mail bids or bidding live online on the day of the auction, but in this business it is important to know your competition and to be seen to be a participant: two things you cannot accomplish from the comfort of home. So, here I was on the bus, book in my lap and, fortunately, nobody beside me smelling of yesterday’s garlic‑rich dinner.

The bus pulled into the Berri Street station on‑time at 10:30. I boarded the Metro for a fast trip to Papineau station two stops east. As I exited the station, I could see MTM International directly across the road. I went into the sale room to register for the auction and examine the notes on my wish list. While auctioneers do their best to identify problems with material, things occasionally go unnoticed, so it is best to avoid surprises by personally inspecting the lots in advance.

The catalogue is often the first chance a bidder gets to see the items up for auction.

The sale room was a hive of activity. About 20 people sat at tables scrutinizing lots, heads bent down with magnifying glasses pressed close to their faces. Two guards who looked very capable of dealing with “incidents” kept watch. Staff scurried behind the tables fetching objects, adjusting lights, setting out snacks or connecting terminals to receive online bids. To the left of the tables was the auction floor itself with its podium, large screens and seating for about 120 people. It was quiet but for a few, small isolated groups having private conversations. This was all about to change.

I later took a seat at the back of the room to get a good view of anyone who might bid against me. At 1:00 pm sharp the auctioneer called the room to order and everyone fell silent. After a few introductory remarks he called out the first lot: a group of military medals and decorations awarded to two former lieutenant governors of Quebec.

When people register for an auction in person, they are given a bidder’s card to identify themselves when bidding. Each bidder is given a unique number for that auction.

I didn’t have long to wait for the French colonial paper money. Within five minutes, the competition was on for lot #12, a piece of card money worth 6 livres dated 1729. Bidding was slow to start, almost hesitant, as buyers felt their way, getting a sense of the competition and not wanting to be overly aggressive and bid too much money. Everyone looks for a bargain even though they know what to expect. The pre‑sale catalogue had conservatively estimated the value of each card at between $5,000 and $10,000 and up to $15,000 for a card in better condition.

I wasn’t bidding on this piece but I could sense the anticipation in the air as prospective buyers watched attentively the auctioneer’s movements. Dealers standing at the back of the room spoke to clients on their cellphones, relaying where the auction stood and bidding on their client’s behalf. Staff at computer terminals called out online bids. Gradually, the bids quickened and the momentum built, growing first by $50 increments, then $100, then $500—and then it was over. After calling a third a final time for additional bids, the auctioneer struck his hammer against the podium and shouted “Sold for $7,500”—a bargain, in my opinion, given the card’s rarity and historical significance. I thought “Wow, I won’t have any trouble buying what I came for.”

How wrong I was!

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

By: Graham Iddon

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon

Welcoming Newfoundland to Canada

By: David Bergeron