War requires funds for supplies, resources and soldiers’ pay. Able-bodied men are taken from the workforce. It’s a heavy burden for a country and adds stress to an economy. For British North America in early 1812, the coming war posed a challenge on all these fronts.

Until 1858, most money in what would become Canada took the form of coins from the United Kingdom, Spain, the United States and France. Some coins, like this Mexican/Spanish 8-reales piece (piece of 8) were revalued in shillings to function as a local currency.

Source: 8 reales/5 shillings, Mexico, Spain, 1805 | NCC 1974.81.3

The burdens of war

The Battle of Queenston Heights, above the Niagara River, was a key conflict in the War of 1812. British and Canadian soldiers, along with Haudenosaunee and Delaware warriors, repelled a larger American force. General Sir Isaac Brock (foreground) died in the battle.

Source: The Battle of Queenston Heights, 13 October 1812, John David Kelly, 1896 Library and Archives Canada, C000273

War seriously stifles prosperity, especially when the theatre of battle is on home soil. This was the situation in Upper and Lower Canada (now Ontario and Quebec) during and immediately after the War of 1812. With the influx of British troops needed to defend the colony’s borders and the recruitment of local men for the militia, the demand for supplies, food, uniforms, equipment, weapons and ammunition mushroomed. Since British North America had extremely limited manufacturing capabilities, most of these items had to be imported. But the bigger issue was how to pay for them all.

The army bill

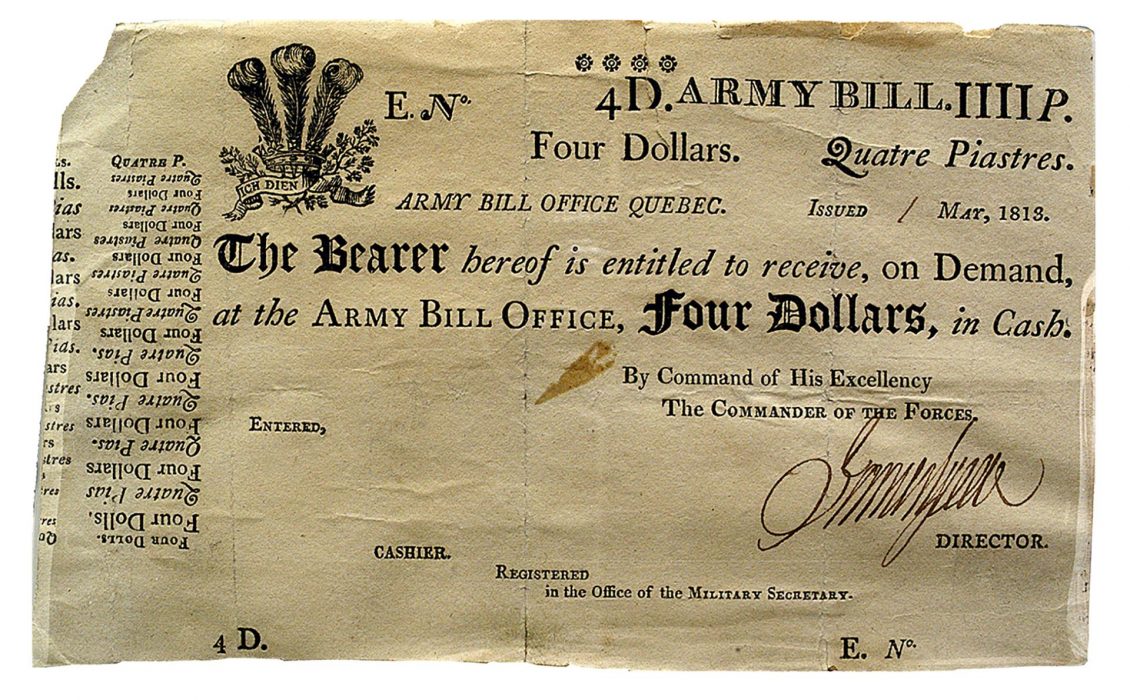

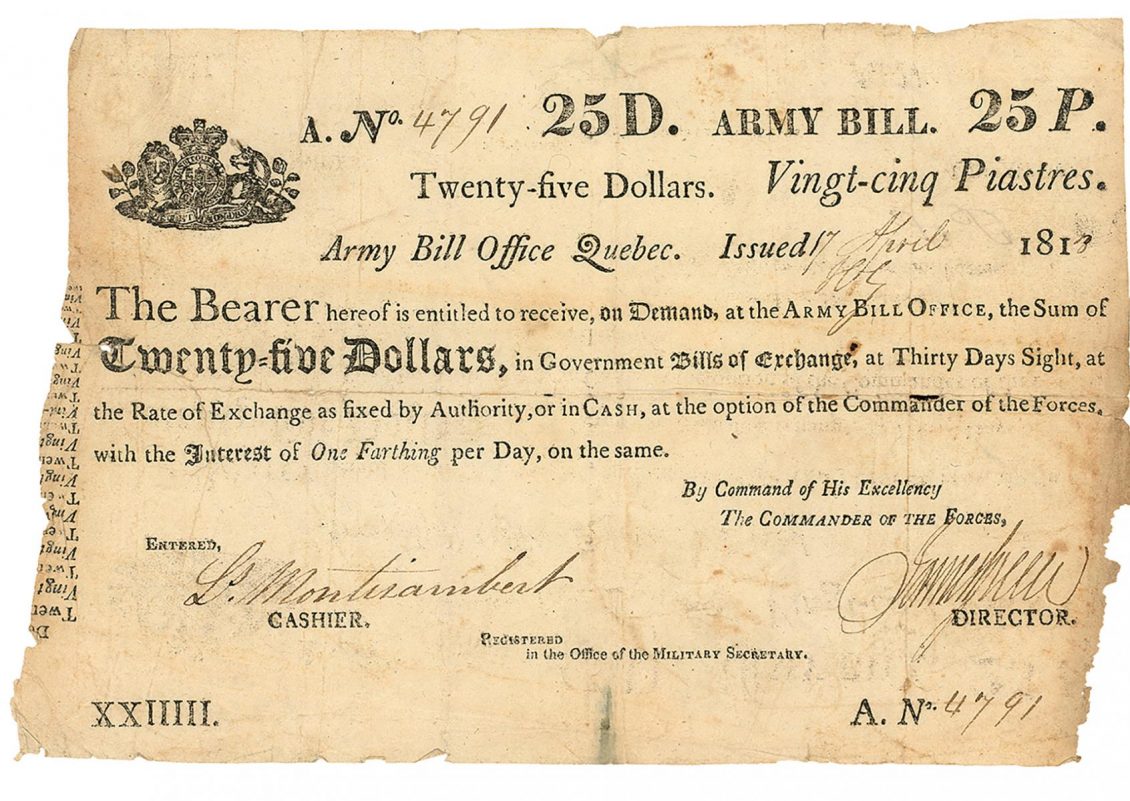

In 1812, British North America had no banks and was starved for any substantial financial resources. With the prospect of war looming, supplies of specie (gold and silver coins) began to dry up and locals took to hoarding hard currency. The government of Lower Canada (Quebec) decided to issue “army bills” to pay for troops and supplies. Most of these notes, in particular the larger denominations, were legal tender—meaning they were authorized by the government. However, unlike today’s money, which is not backed by anything tangible, army bills were backed either by cash, for the small notes, or by bills of exchange payable in London, for the larger denominations. The bills of exchange could eventually be traded in for silver or gold in Great Britain. The main purpose of the army bills was to provide a circulating form of payment for local suppliers and to pay the troops. While they were designed to function in the economy, they also acted as a government treasury bill.

A supplier to the militia who was paid in army bills was effectively offering the government a small loan that the government would later pay back in hard currency. Unlike the bonds used to finance the First and Second world wars, army bills circulated in the economy just as our paper money does today. If the militia bought boots with army bills, the cobbler could turn around and spend those bills as they would any currency, at another business. To keep army bills in circulation and to inspire public confidence, the larger bills paid interest at 4 pence per £100 per day, or 6% per year. Like a war bond, the interest was payable when the notes were returned to the government at the end of the war.

The Army Bill Office opened in the city of Québec late in the summer of 1812. Initially, £250,000 ($1 million) worth of notes denominated in $4, $25, $50, $100 and $400 were issued. Later, $1, $2, $3, $5 and $10 notes were added.

John Neilson of Québec was given the contract to print the new notes. They varied in size from that of our current bank notes to at least half a sheet of letter-sized paper. None of the larger denominations have survived, so we don’t know how big they were. New notes were bound in a book and each note had a printed security feature called a “counterfoil”: a series of words in small type running down the left edge. Removing a bill involved cutting through its counterfoil. When the bill was brought back to be traded in for cash (redeemed), it had to match the stub left in the book and complete the counterfoil. It was a crude, but very effective anti-counterfeiting measure.

A costly war

While army bills totaling £3.44 million ($430 million today) were issued during the war, the estimated cost of the war amounted to £5.92 million ($740 million), according to the accounts of the Commissariat (supply arm of the military). The last army bills were issued in February 1815, to cover any outstanding balances.

People were allowed to begin redeeming notes the following month and, by February 1816, the value of outstanding army bills was just over £330,000 ($1.32 million today). By January 1817, this number was down to about £65,000 ($260,000). When the Army Bill Office closed for good in 1820, £819 ($3,276) in army bills hadn’t been redeemed. Today, these notes are extremely rare—the Bank of Canada Museum holds the majority of remaining army bills in its National Currency Collection.

Smaller bills likely circulated in local economies where cash was extremely hard to come by. Some of these notes have complete counterfoils, which indicate they were never issued.

Source: 1, 3, 5 and 10 dollars, Army Bill Office, Canada, 1813–14 | National Currency Collection

Paper money the people trusted

Perhaps due to fears of counterfeiting or inflation, the army bills had been taken quickly from circulation. Without plans to replace them with a similar item, their quick withdrawal and redemption put a greater strain on the already shaky currency supply in Upper and Lower Canada. Nonetheless, Army bills were considered a success. They represented a convenient form of money at a time when access to hard currency was inconsistent. They were widely accepted and circulated freely. Because some of the notes paid interest and all were fully redeemable, army bills were seen to have re-established the public’s confidence in paper money.

The 19th-century legalese on this note simply states that the owner of this army bill will be able to trade it for a government bill of exchange, which will then be redeemable for gold and silver at a later date. It also notes the interest rate: 1 farthing per day.

Source: 25 dollars, Army Bill Office, Canada, 1813 | NCC 1997.25.1

The dawn of Canadian banking

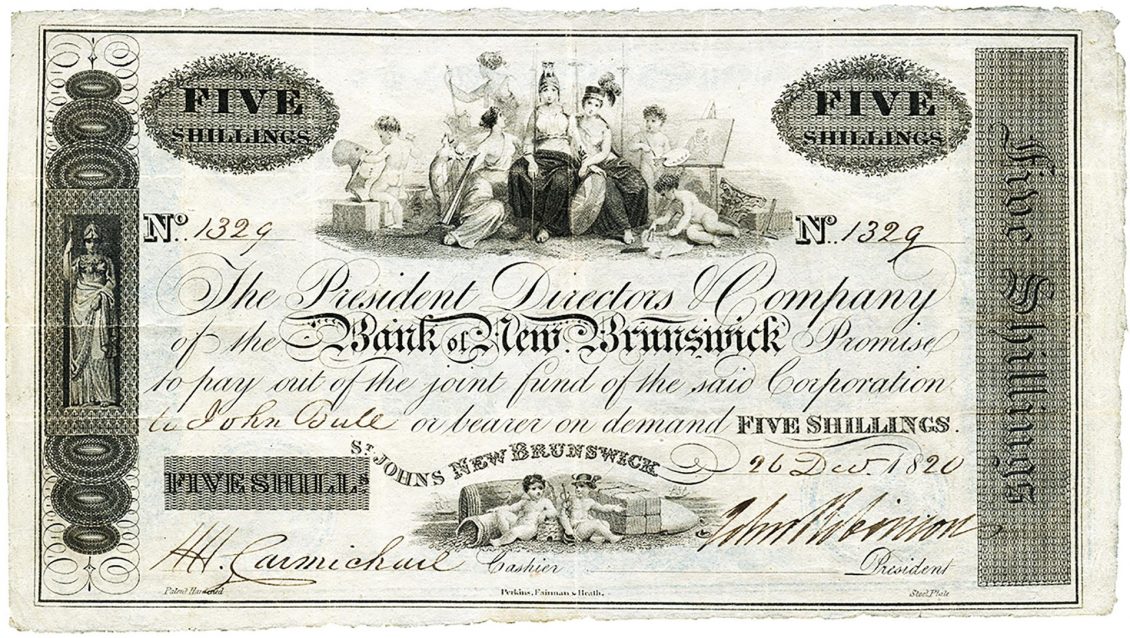

After the fall of New France in 1763, many businesses in Upper and Lower Canada were stuck with worthless card money and ordonnances, French forms of temporary paper money that had also replaced hard currency. So, for the next half-century, merchants wanted nothing more to do with paper money. But the success of army bills meant citizens were far more receptive to bank notes and banking. Over the next few decades, dozens of banks would open in what would become Canada. Many were solid, worthy enterprises and are still in business today, while others were unreliable or downright fraudulent. Regardless, all would issue bank notes and 19th-century Canadians would come to accept them.

The Bank of New Brunswick was Canada’s first chartered bank—licensed in 1820 by the British government. It was followed in 1822 by the Bank of Montreal.

Source: 5 shillings, Bank of New Brunswick, Canada, 1820 | NCC 1966.21.4

The Museum Blog

Webinars

Join us for fascinating talks by Museum and Bank of Canada experts. Register for upcoming events or catch up on previous presentations.

Saving and spending

Students will experience financial goal setting, planning and setbacks. They will plan for a character’s short- and long-term financial goals by using saving and spending strategies.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.