From windmills and solar panels to electric cars, signs of the green economy are all around.

What is green economics?

Society faces a major transition ahead to curb climate change and reverse environmental degradation. Green economics looks at how economies based on fossil fuels can make this transition. The United Nations Environment Programme describes the green economy like this:

“A green economy is defined as low carbon, resource efficient and socially inclusive. In a green economy, growth in employment and income are driven by public and private investment into such economic activities, infrastructure and assets that allow reduced carbon emissions and pollution, enhanced energy and resource efficiency, and prevention of the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.”

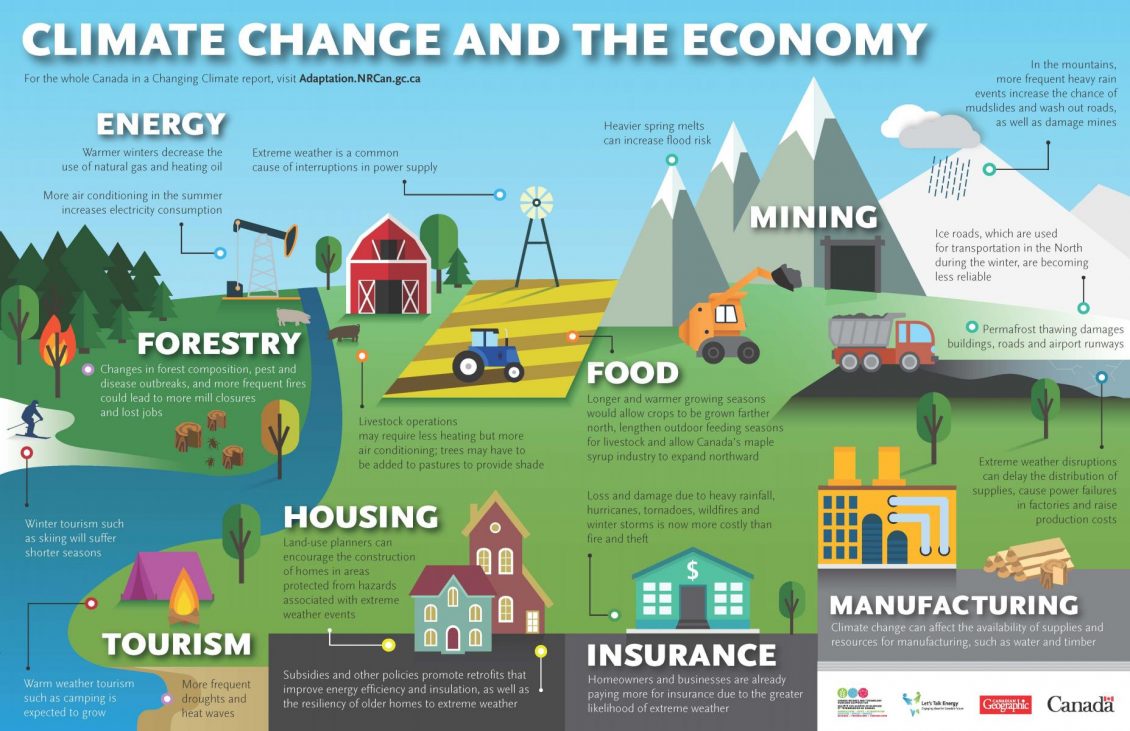

The effects of climate change on the Canadian economy will be significant and affect many sectors.

Sources: Ingenium, Natural Resources Canada and Canadian Geographic

Impact on youth

Consumers choose how to spend their money. These choices can influence companies’ social and business behaviours, including their environmental practices. Young people are key players in raising awareness about, supporting and adopting environmentally friendly practices. What’s more, they are demanding to know why green technology may appear slow to be widely adopted.

The Bank of Canada Museum has gathered a few resources and entry points for a classroom exploration of the green economy. Look over the following concepts and resources, and let us help you begin a conversation.

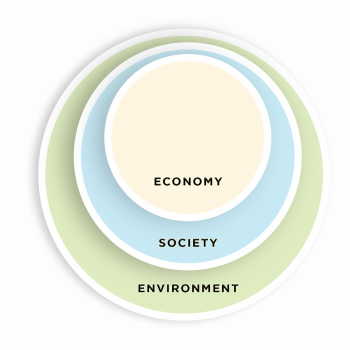

A model for sustainable development

A common approach to sustainability considers the environment, society and culture, and the economy. The planet takes care of pollinating plants, purifying the air and naturally storing carbon. Because these ecological “services” are necessary for human survival, economists are beginning to quantify nature’s contribution to the economy, calling it natural capital.

Get the conversation going

Have your students consider each element first (economy, society, environment) and then look for interrelationships:

- Create a Venn diagram with overlapping circles, one for each element. Brainstorm the common features shared by all three.

- What environmental, labour and economic factors do you consider when making purchases?

Explore the idea of natural capital:

- Which of the planet’s ecological services are important for your regional economy in particular?

- Has someone attempted to give them a dollar value? Look online for research.

Get the inside scoop on externalities

An externality is a cost or a benefit generated by the production or use of a good that is not accounted for in the price of that good. The externality affects more than the producer and user of the good, and it can be positive or negative. For example, the most common negative externality in many manufacturing industries is pollution.

In economic terms, climate change is a negative externality. Any individual or company that engages in activities that generate greenhouse gases imposes a cost on everyone else by contributing to climate change. Establishing a price for carbon emissions forces polluters to bear those wider societal costs.”

Tim Lane, Deputy Governor

If factory owners don’t have to pay for the cost to society of the pollution they create, they don’t need to raise their prices. Nevertheless, consumers still pay for the cost of the pollution. For example, eco-fees are added to the price of new electronics to try to account for their recycling cost or proper disposal.

Green economic initiatives, such as taxing pollution, are intended to correct negative externalities. And projects that take green economics into account might well go beyond simply reducing pollution. They could, from the start, encourage building spaces with health and well-being in mind; this could include increasing biodiversity or favouring more active forms of transportation such as cycling and walking. These would be positive externalities.

Watch the video below and use the accompanying discussion guide to encourage your students to look at externalities through a green-economy lens.

- What kinds of positive or negative externalities might the green economy address?

- What costs are being factored into today’s products to deal with externalities?

Accounting for externalities means the environment is not an afterthought in industrialization.

Taxing, capping and trading pollution

Economists are fascinated by incentives and disincentives. An important conversation about the green transition centres on putting a price on pollution, thereby encouraging individuals, companies and governments to reduce their use of fossil fuels. For example, governments may put a price on greenhouse gas emissions, using taxation to discourage increased pollution. Or they might put a cap or limit on emissions. The incentive to lower emissions might be a tax credit or grants to help support green technologies.

How a carbon tax reduces emissions

Most carbon-intensive fossil fuels are taxed based on how much greenhouse gas (GHG) they emit. The added cost is passed up or down the supply chain, so even if one group is taxed (industry) and another is not (homeowners), the tax still affects everyone.

Most emissions are taxed by raising fuel prices across a region.

In most cases, governments use revenue from carbon taxes to provide personal tax breaks or to help pay for lower rates for labour and business investment. The tax funds may be used to stimulate other parts of the economy.

So, to avoid the higher prices of fossil fuels, consumers will turn to affordable and more energy-efficient alternatives, thus cutting their carbon emissions.

Higher prices on fossil fuels combined with increasing demand for alternatives will ideally encourage innovation. Then the production of low-emission technologies and renewable energy sources will become more competitive.

Big industry emitters will adjust their practices. They’ll invest in technologies such as carbon capture and storage to help cut back on their GHG production.

Emissions will be reduced across the country.

Source: Adapted from N. Walker, “The Price is Right,” Energy Exchange, Winter 2016.

How a cap-and-trade-system reduces emissions

The provincial government creates an emissions-trading market by turning reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into a commodity. It decides which sectors to regulate and sets an overall cap, or limit, on how much GHG each industry is allowed to emit each year. It also sets the lowest and highest price (known as the floor and ceiling) for a permit to produce one tonne of GHG.

Some industries (such as pulp and paper, steel and cement) are exposed to tough international competition and cannot pass on the cost to local consumers. These industries are often given some permits for free.

The government raises revenue by selling the remaining permits at auctions throughout a year. Businesses purchase the fewest permits needed to cover their annual emissions.

Businesses that produce more emissions than the cap allows attempt to reduce their carbon emissions at the lowest possible cost. Some cut down on emissions, allowing them to bank their permits or sell them to firms that exceed the cap.

Firms in sectors without a cap can generate “offsets”—a type of lower-value carbon permit. Firms earn offsets by lowering their emissions or taking on other carbon-reducing projects. They can sell their offsets to industries that have a cap. This broadens the reach of the cap-and-trade program and helps achieve an overall emissions reduction goal.

The cap is set at a lower level than many firms’ current emissions, which means emissions must fall by a set amount. Firms whose emissions exceed the cap face fines and other sanctions. The pressure to meet certain levels creates incentives for industries to invest in cleaner, innovative technologies or energy research.

At the end of the year, regulated firms submit a verified emissions report and surrender permits and offsets equal to their emissions.

The more businesses and carbon markets are included, the less volatile the price of carbon is. Once a region’s trading program is established and stable, its carbon market can be linked with others.

Emissions are reduced across the economy. Over the years, the government ratchets down the overall emissions cap, issuing fewer permits and slowly raising the minimum (floor) permit price.

Source: Adapted from N. Walker, “The Price is Right,” Energy Exchange, Winter 2016.

Explore cap and trade and carbon taxes using the above illustration.

- Have your students look at the different stages of the process and draft their own list of pros and cons for one of the solutions.

- Afterward, discuss with your students their lists in small groups and then together as a class. What approach would they take?

Analyzing pathways to energy transition

Energy and natural resource exports are a large part of Canada’s economy. A green economy would move away from some fossil fuel products for both internal use and export. Transition fuels such as natural gas are being used to replace coal, while electricity systems are being modernized to support the widespread use of electric vehicles.

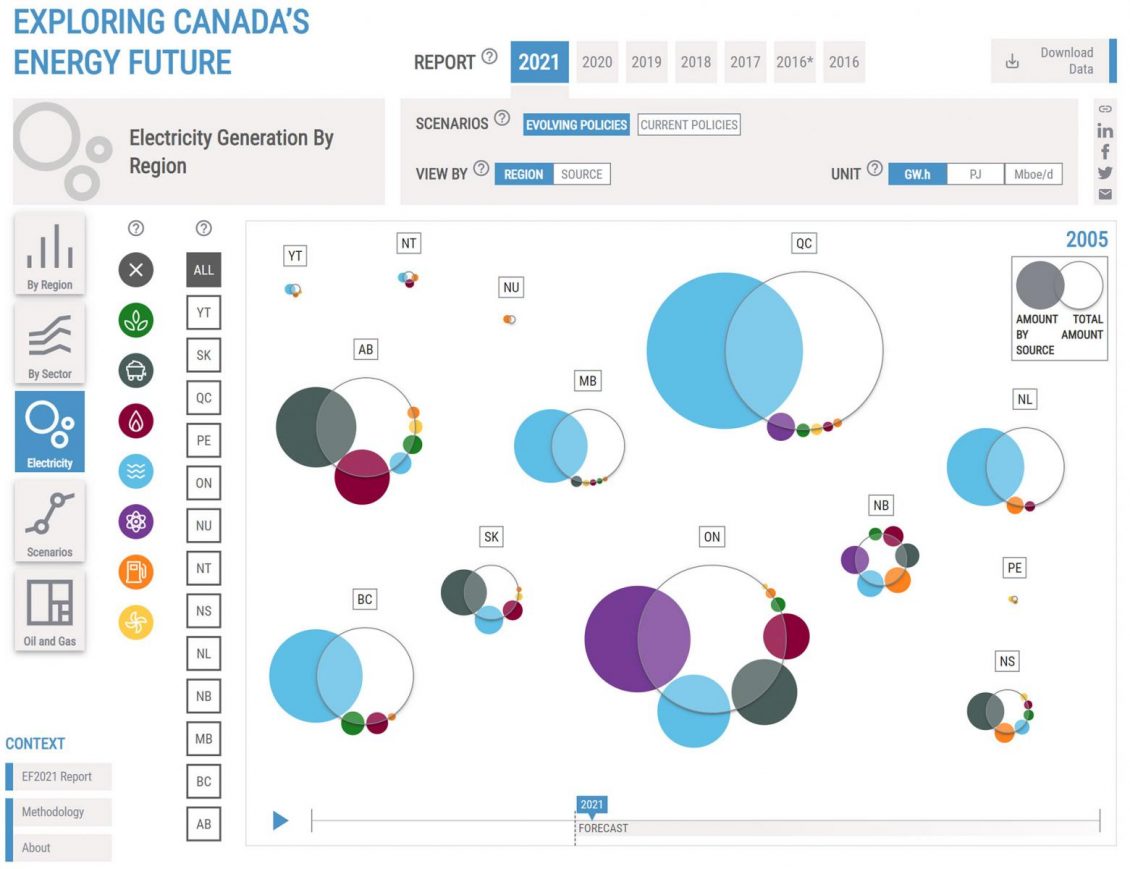

The Canada Energy Regulator has developed a series of data visualization tools to compare energy scenarios as policies change. With “Exploring Canada’s Energy Future,” you can choose different timelines and scenarios to compare a low-carbon and a high-carbon future.

Forecasting low or high-carbon emissions will determine Canada’s future energy sources.

Source: Canada Energy Regulator

Explore these visualizations with your students to see how a shift to lower emissions shapes the kind of energy that is produced and consumed.

- What sorts of jobs might become more common?

- What provinces, territories or regions would see the most change? How does your region compare with others in the projections over time?

- Why do you think this is so?

- Research your local energy policies and compare them with national targets to get a better idea of the differences.

- Look at the adoption curve for a green technology, such as solar panels, to better understand the costs for early adopters and the shift to widespread adoption.

Measuring climate risk (it comes down to finances…)

The Bank of Canada assesses risks to the Canadian economy to predict future challenges. The Bank’s economists have created a few scenarios that look at climate risks in particular.

There are two kinds of risks to the economy from climate change:

- Physical risks: Extreme weather and temperatures can cause extensive damage to buildings as well as roads and other infrastructure.

- Transition risks: Transitioning to a low-carbon economy will lead to significant adjustments to labour, machinery and technology.

What is the cost of climate change? The International Energy Agency estimates that transitioning to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions—in other words, moving the economy and energy sources away from most fossil fuels and to cleaner energy and growth—by 2050 will cost governments and businesses worldwide trillions of dollars a year.

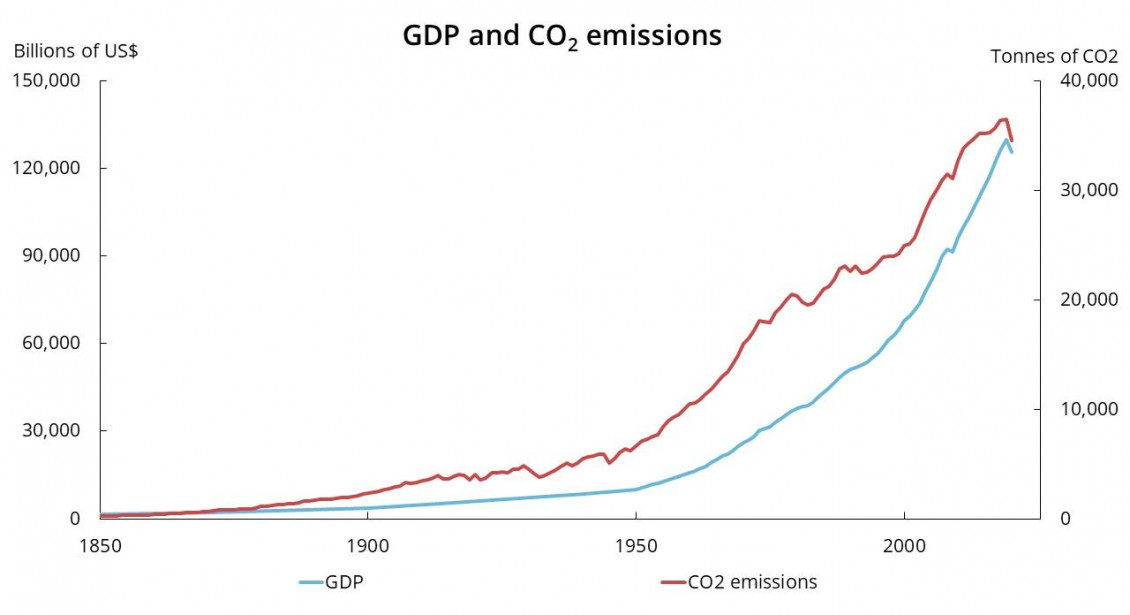

However, the cost of doing nothing would be much higher. While the impact of physical risks is uncertain, most studies predict a loss of over 5% of global GDP with 4 degrees of average global warming. This temperature increase far exceeds our current target of 1.5 degrees of warming by the end of the century to reduce the risk of irreversible climate change. These climate-economy models demonstrate how climate change and economic changes function together.

Traditionally, countries with the largest CO2 emissions also saw the most economic growth. However, economic growth and CO2 emissions are starting to decouple—or detach from each other.

Sources: World Bank, The Maddison Project, Potsdam Institute For Climate Impact Research, Global Carbon Project and Bank of Canada calculations

As the risk of climate change to financial systems is becoming clear, insurance companies are raising premiums in response to increased extreme weather such as flooding and wildfires. Some banks and corporations may also pull out of emissions-intensive sectors that could face high transition costs or become obsolete.

The large size of Canada’s oil and gas industry means that Canada is more exposed to an energy transition than other countries. It is likely Canada’s GDP would therefore go down if global oil demand were reduced. Major changes to our economy will need to be considered. Investments in energy, technology and new green sectors will bring new jobs and growth.

Make a mind map to brainstorm the different risks of climate change to the financial sector.

- How might the impact of climate change affect you as a consumer and an individual, along with society around you?

- Consider recent extreme weather events brought on by climate change. How do they impact the financial sector and your day-to-day life?

Global goals

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes 17 sustainable development goals (commonly referred to as the SDGs or Global Goals). The Global Goals provide a great framework for understanding the idea of sustainability and how positive actions in one area can impact other areas. Many of the Global Goals are directly connected to the green economy—or the positive externalities that result from the transition.

As part of our country’s commitment to working toward all the Global Goals, Statistics Canada and other government departments and agencies track indicators in many areas.

Source: The sustainable development goals are part of Agenda 2030.

The Global Goals can help students take part in a global cause and see their own actions within a larger framework. Review Canadian data through the Sustainable Development Goals Data Hub on Statistics Canada’s website.

- What indicators is Canada tracking related to the green economy and green energy?

- Pick one Global Goal and come up with one action to address it, such as solar energy or reforestation. Have students discuss how their actions impact the green economy on a global scale.

- Pair students up and have them think about different ways they could measure progress toward achieving green goals within their school or community.

Green financing

Like any other program or service, green projects often need start-up or support funding. And a hugely popular green bond and green stock market has popped up. Encouraged by the plummeting cost of renewable energies, investment firms, individual investors and pension funds are increasing their support of projects that factor in the environment.

Watch the video below for more information on the role of green financing and its connection to governments and their central banks.

Green financing requires long-term investments and policy support from many levels of government, including central banks.

As a class, brainstorm some examples of companies your students would consider green, or eco-friendly.

- Why do you think these companies are green? What do they have in common?

- What impact does production and consumption of their goods have on the environment?

- Have students research companies’ statements and actions about sustainability and the Global Goals. Ask them to consider the concept of “greenwashing”—actions to make a company look more eco-friendly than it actually is. Can they spot any questionable environmental statements or advertising?

Have your students create their own imaginary basket of shares from companies they think support a green economy.

- Why did they choose those companies to invest in over other ones?

Conclusion

The green shift is an evolving story of actions and decisions that may not always be widely understood. This transition is particularly interesting to young people today who are affected by choices made by generations before them. While the green economy is a complicated system, everything is tied back to the natural world. The daily choices everyone can make to support local and green initiatives also can play a part.

It is crucial that the natural world is protected for generations to come. After all, people are the economy, and we have a choice in shaping its future.

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.