A riveting tale of wartime foreign currency reserves

When Britain or any other country imports goods from Canada, they must be paid for in Canadian dollars. During the Second World War, however, English currency could not be changed into other currencies.

Canada was a major supplier to the besieged island nation, and the United States was a major supplier to Canada. Britain couldn’t pay us for our exports to them, and we were getting short on US dollars to pay for imports from the United States. We were caught between a rock and an expensive place.

During the Second World War, the US dollar was like gold to Canada—both literally and figuratively.

1 dollar, United States, 1935

In 1939, the Bank of England made the pound “inconvertible.” Because it could not be exchanged for other currencies, English money stayed at home to keep the local economy functioning.

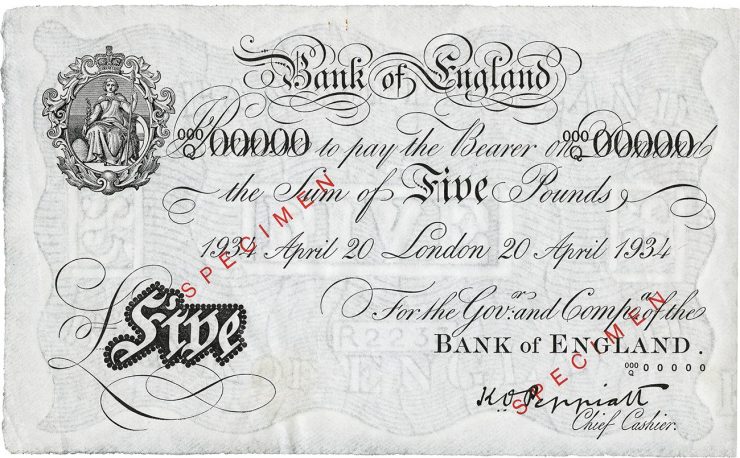

5 pounds, Great Britain, 1934

Fortunately, somebody saw this coming

All nations hold reserves of foreign money. It is a means of keeping liquid assets on hand, as well as providing appropriate currency to buy foreign products. Then, as now, the majority of most nations’ foreign reserves was in US dollars. As war loomed in Europe, Bank of Canada Governor Graham Towers recognized the likelihood of an enormous US trade deficit. He feared that we might not have enough foreign cash for immediate future needs. To address this issue, the Bank created the Foreign Exchange Control Board (FECB). One of its major tasks was to find as many US dollars as possible to pay for American imports of war material. It would do this largely by controlling the flow of US dollars and gathering those dollars into the government’s foreign reserves. The FECB would try to ferret out every available greenback in Canada. From hockey players’ US salaries to a few bucks in a birthday card for a cousin in Buffalo, no amount was too small.

The board of the FECB, 1941. Donald Gordon, the Alternate Chairman, is at the head of the table; Louis Rasminsky, who will later co-run the department, is third from the left.

Photographer unknown, Bank of Canada Archives, 1941

In a scene straight out of a Bond film

A few days after Canada declared war on Germany, a group of senior officials from the chartered banks was invited to the Bank of Canada. On the morning of September 15, they were locked together in a room. At 10:00am, Governor Towers appeared and introduced them to the extraordinary plan the FECB was to undertake. The banks were to act as agents of the Bank of Canada in registering, restricting and directing the flow of US and other foreign currencies.

Governor Towers briefed the officials on their roles and left the room. Unable to even call their offices, the officials were then compelled to remain at the Bank until the FECB had been given its official go-ahead by the government. Then the plan went into high gear. The hapless bankers weren’t released until 6:00pm!

In an operation as complicated as anything the military could dream up, all the manuals and forms to execute this plan had been secretly prepared well in advance. Individually bundled and addressed for post offices, customs houses and over 3,000 bank branches, the packages were delivered before the morning mail on September 16th. Bankers and postmasters all over the country likely spent a few hours that day struggling with the dense complexity of The Manual of Instructions to Authorized Dealers under the Foreign Exchange Control Act and Regulations.

By late spring 1940, France had fallen. Convoy after convoy of freighters steamed out of Canada’s eastern harbours to an isolated Britain. Canada relied increasingly upon US imports to help fill those cargo holds, and the Bank of Canada needed to scrounge for every American dollar it could find—and fast.

It was up to the banks and post offices to enforce the FECB’s rules. All requests for US money were carefully regulated, and every Canadian purchasing or selling US dollars had to fill out a number of forms. Travel to the United States was restricted, and expenses for US travel were closely checked. Nobody was exempt from scrutiny. Even Louis Rasminsky, who, by 1943, effectively ran the FECB, had to justify his expenses on official trips across the border.

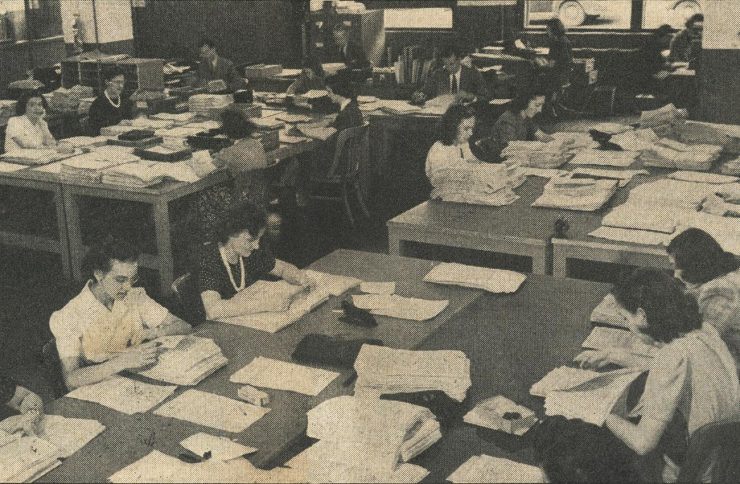

Hundreds of workers were hired to manage all the paperwork of the FECB. They were housed in a temporary building on the east side of the Bank’s head office.

Photographer unknown, Bank of Canada Archives, 1941

Thousands of permits were issued daily for all transactions between the countries, and as soon as US money came into Canada, it was immediately placed into the reserves. The FECB even went so far as to search mail for US currency. This might seem petty, but, in 1943 alone, around US$5,000 per month was diverted from the mail and changed for Canadian money.

Inviting the greenback to Canada

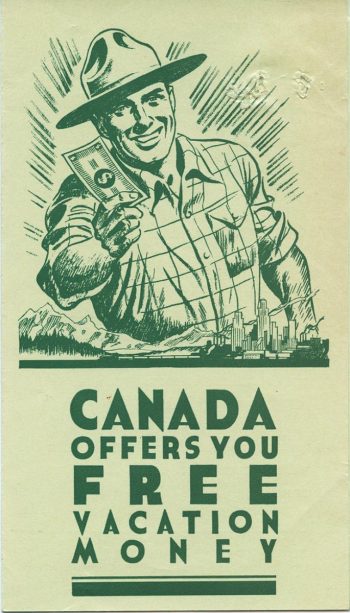

A wartime Canadian tourism promotion: “…the fish are just as plentiful, the scenery just as magnificent and the people just as friendly as they’ve always been.” FECB (F141.v6), Bank of Canada Archives, around 1941

Fears of spies and saboteurs often encourage governments to limit the number of foreigners entering a country in wartime. Bank of Canada stats of the era estimated that tourism accounted for 30% of Canada’s export trade market. Governor Towers felt that entry restrictions would not be worth the loss of American tourism dollars and openly argued against such restrictions:

"The amount of U.S. dollars we might lose through [tourism] restrictions might be the equivalent of a thousand planes…"

So, the FECB became tourism promoters, using radio commercials, newspaper articles, pamphlets and posters to sell Canada as a vacation destination to Americans.

Canada needs foreign exchange in the worst way. In particular she desperately needs American dollars. Those American dollars go to buy planes and munitions of war from the United States. The more American dollars we can scrape together, the more planes, guns and things like that, we can buy. Now the readiest means of laying our hands on American cash, laid on the line, is through the tourist traffic.

CBC national broadcast, June 17, 1940

And the American dollars would roll in. Tourism increased by 10% in 1941 with a greater rise in 1942: proving the “every little bit helps” philosophy of the FECB.

A temporary effort

Louis Rasminsky influenced all levels of the FECB, but his best talents lay in organizing international finance. Greatly respected in Washington and abroad, he became the Governor of the Bank of Canada in 1961. Photographer unknown, Bank of Canada Archives, around 1938

The FECB’s job became increasingly easier after the United States entered the war. Canadian and the US industries could supply one another with resources and goods in a flexible trade partnership, and the dollars flowed in both directions. Large-scale American projects in Canada, such as airfields or the Alaska Highway brought in plenty of American cash. By 1943, Canada had more than enough US dollar reserves for its wartime needs.

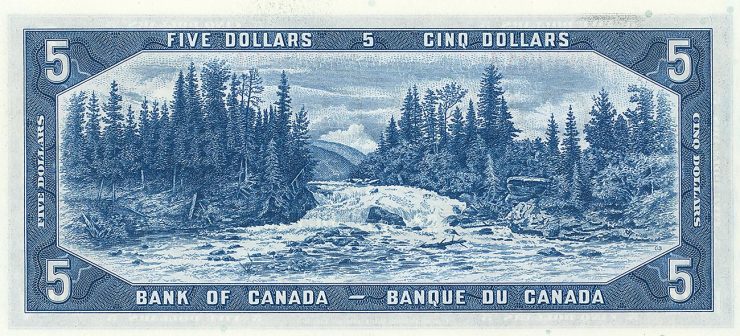

Otter Falls, Yukon Territory at mile 996 of the Alaska Highway. The 2,700 kilometre route was completed in 1942, connecting the lower US states with Alaska, safe from possible Japanese attack.

5 dollars, Canada, 1954

The FECB relaxed its regulations as the war progressed, but continued to keep a hawk eye on US dollars. Some aspects of its operations continued well after the war, smoothing the transition to a peacetime economy. The FECB was entirely disbanded in 1951.

Nowadays, the Bank holds roughly $50 billion in US reserves and around 25 billion in other currencies. Compared with other nations, Canada’s holdings are quite moderate. We use these funds not just for imports but as insurance in case we need to stabilize our own dollar. We haven’t needed to use foreign reserves for this purpose for 20 years, though we have used our reserves to assist other countries to do so. Learn more here.

Further reading and bibliography

- D. H. Fullerton, Graham Towers and His Times (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1986)

- G. S. Watts, The Bank of Canada: Origins and Early History (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1993)

- B. Muirhead, Against the Odds: The Public Life and Times of Louis Rasminsky (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999)

- J. Powell, A History of the Canadian Dollar (Ottawa: Bank of Canada, 2005)

- T. Lane, Taking Precautions: The Canadian Approach to Foreign Reserves Management (speech to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC, February 6, 2019)